KNOW YOUR MAYORS Our modest little series about some of the greatest, notorious, most important, even most useless, mayors of New York City. Other entrants in our mayoral survey can be found here.

Mayor Jacob Westervelt

In office: 1853-1855

Dutch-blooded Jacob Aaron Westervelt, 24th man to become mayor of New York since the British evacuation of 1783, lived in a two-family home at 308 East Broadway near Grand Street. This seems like a rather odd spot for a mayoral residence today, and perhaps even then. Today there is no 308 East Broadway, there’s only a grim-looking public school and a barren traffic island.

But there are some surviving row houses just down the block — preserved Federal-style buildings at 247-249 East Broadway — so just imagine a fancier version of these on the spot that Westervelt’s residence once stood, many years before this neighborhood would become associated with squalor and overcrowding.

Now image this: an angry mob of 5,000 men with torches, surrounding this very home in the winter of 1853, painting a cross on the doorway and crying for his head. His crime: he sides with Catholics. Scandal! What would a mayor have to do garner that sort of reception today?

Westervelt is better known today for his original profession as master ship-builder. Few men who served as mayor of New York were better regarded internationally as Westervelt, who once received an honor from the king of Spain for making them some of the fastest ships in the sea.

Jacob was born twenty days into the year 1800 in Tenefly, New Jersey, but moved with his family into New York when he was only four years old. His father was a builder and constructed several new homes along Franklin Street, near the area being drained of that marshy, polluted mess known as Collect Pond.

By age 14, Jacob was apprenticing with famed shipbuilder Christian Bergh at his shipyard off Corlear’s Hook — not coincidentally more than a few blocks from Westervelt’s later residence as mayor.

Bergh would spawn one of New York’s wealthiest families, although incongruently his son Henry Bergh would become the best known member — as the founder of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Henry is also known for this weird mausoleum at Green-wood Cemetery.

The Berghs would eventually abandon shipbuilding after Christian’s death. His young apprentice Jacob would carry the torch for him, eventually taking over Bergh’s shipyards, expanding with other business partners up and down the East River shore, and using southern American and European connections to soon dominate the shipbuilding business. By 1845, Westervelt had overseen the construction of dozens of clippers, schooners and steamships, among the fastest and most reliable on the Atlantic Ocean.

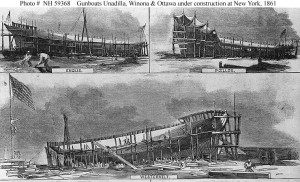

Below: an illustration of various boatbuilders in 1861, including Westervelt at bottom

As a pioneer of reliable and innovative shipping vessels, Westervelt’s influence was felt internationally. In the world of mid-19th century politics, that made him an ideal candidate for public office, and especially to Democratic machine Tammany Hall. As one of Manhattan’s most visible men of industry, Jacob employed hundreds of new Irish immigrants, Tammany’s prime voting bloc. In fact, Westervelt had already briefly served as council alderman for his district in 1840.

In 1852, Tammany could use a man of relatively unblemished character. The stench of corruption was already swirling around the powerful, entrenched Democrats in office — and this was in the years before Boss Tweed! Derisively known as the Forty Thieves**, the Democratic aldermen in City Hall were easily and openly bought, by everyone it seems but the mayor at the time, anti-Tammany reformer Ambrose Kingsland. City expenditures swelled, the elaborate web of political kickbacks and bribery gelling during this period.

But Tammany was looking to start fresh — or at least strike the apperances of doing so — choosing Westervelt as their reform-lite candidate in 1853, a symbol of prosperity in a wobbly New York economy. Westervelt, on the surface, looked like somebody who could quell the city’s massive over-expenditure. On the strength of a surging Democratic national ticket with presidential candidate Franklin Pierce, Westervelt was easily elected by the largest margin yet during a mayoral race, defeating the now-forgotten Whig Morgan Morgans.

Although, this being the 1850s, one can assume that total to be highly suspicious. “No registry law was in force to hinder men from voting…as often as twenty times,” claimed one early history.

Westervelt inherited several massive projects which were bloating the city budgets, including Central Park. Already a done deal when Westervelt entered office, the mayor sought to cut the park space in half due a bloated, overwhelmed city budget. Had Westervelt ruled the day, Central Park would have started on 72nd Street! His plans would be reversed a few years later by Mayor Fernando Wood.

More appropriately, Westervelt became president of a world’s fair in 1853, more specifically called the Great Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations and housed in the glorious Crystal Palace in the area of today’s Bryant Park. Having a man of industry preside over a fair of industry was both fortuous and apt; certainly examples of his own creations were displayed with other technological marvels of the age like the elevator.

Below: the well-uniformed Crystal Palace police officers (pic courtesy NYPL)

One of the mayor’s lasting contributions was in New York police reform, creating a Board of Police Commissioners with himself in charge to apply a strict code of ethics to an already chaotic, corrupted body. In doing so, he wrangled away from his more corrupt Democratic brethren their ability to buy and sell police jobs as a form of political patronage.

But his most radical idea is today the most obvious: he mandated that every police officer should wear a uniform, an “expensive and fantastical” requirement according to his opponents who believed it “unrepublican to put the servants of the City in livery.”

Westervelt managed to make himself with one very unpopular with one group: the Know-Nothings, a ‘native American’ group who feared the swelling hordes of Irish and Catholic immigrants and the Catholicism they brought with them. The group would reach peak influence across the country in the mid-1850s, and they would actually gain significant political traction in other cities. In New York, they more often showed their moxie in the form of rioting.

The mayor earned their ire on December 11, 1853, when he ordered a street preacher arrested for gathering a group of 10,000 to listen to his frothing Know-Nothing spiel. It probably didn’t help matters that said preacher had organized on Westervelt’s own wharfs on the East River!

At the beginning of this article, I mentioned Jacob’s address — 308 East Broadway. A bit out-of-way of New York’s high society, sure, but Westervelt wished to be close to his ships. In fact, he and his partner Robert Connelly both built adjoining houses on this spot, facing Grand Street. According to Harper’s, “Over the door was a large stone cap on which was carved the representation of a ships taffrail.” (Taffrail is nautical for “the upper part of the ship’s stern“)

Thus, the angered Know-Nothing crowds were scant blocks from the mayors door. A reported 5,000 men gathered outside Westervelt’s home, demanding retribution and the release of the arrested preacher. To remind the mayor what this argument was all about, they painted a gigantic cross upon the door.

Thus, the angered Know-Nothing crowds were scant blocks from the mayors door. A reported 5,000 men gathered outside Westervelt’s home, demanding retribution and the release of the arrested preacher. To remind the mayor what this argument was all about, they painted a gigantic cross upon the door.

This story outlines Westervelt’s uneasy dual role as city leader and businessman. In 1855, the ships won out. Jacob bowed out, allowing Wood to finally ascend to the mayor’s desk for the first time. His best work as a shipbuilder was indeed ahead of him, though he would make brief returns into the political fray, first as a state senator, then in a newly created job in which he was most qualified — the New York commissioner for docks and ferries, from 1870 until his death in 1879. He died at his home on 63 West 48th Street, in the area of Rockefeller Center today.

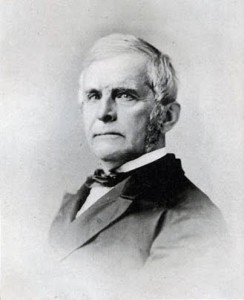

Pictured at right: Westervelt at age 70

** Not to be confused with New York’s first gang, also called The Forty Thieves

5 replies on “Mayor Westervelt: “Police officers must wear uniforms!””

Did Westervelt do anything to improve Five Points during his tenure in office? Wasn’t the attempt at clean-up by the Methodists during his time in office? Also, do any of the first police uniforms survive in any NYC museums?

He was my great great grandfather, mother’s mother’s side so no shared name. Thanks for the info. I suppose we’ve always been a controversial bunch.

Some of my early family members resided at 308 East Broadway- Dr. Louis A Falk and his family. It is noted on the 1910/20 census. I just wonder if it was the original building structure. Also, if there exists a photo of this home/building.

Laurie

gennyfish, he was also my great great grandfather

on my mother’s side.

Linda L. Westervelt Montoya Sep. 25 2013 1:15 He’s my Great. Great Grandfather my Fathers side What an awesome man he has the same expression on his face as dad in the older picture