In this week’s podcast, I refer to New Yorker and Trinity Church benefactor William Kidd as one of the most notorious pirates of the Atlantic Ocean. Now I feel that might have been a bit of slander.

It is true that Kidd, forever known to generations of seafarers as Captain Kidd, was vilified by the British for illicit profiteering and eventually hanged in London on May 23, 1701. But Kidd himself fought off the charges voraciously, and today historians believe Kidd was scapegoated and was himself following orders of the governor of the New York colony himself — Richard Coote, the Earl of Bellomont. Yes, the man who tried to annul the charter of Trinity Church!

I’ll save the details of Kidd’s exploits for various pirate-themed blogs. Kidd may have been prosecuted unfairly, but the legend that arose around his real or imagined exploits makes him one of New York City’s most notorious residents of the 17th century. Not only was Kidd one of early New York’s most wealthy residents, but almost without question he had one of the best views in the city from his bedroom.

According to historian Richard Zacks, New York was “the pirate port of choice in the English colonies in North America” in 1690s, with its rich harbor and its relatively multi-cultural port. Still a volatile colony amongst England’s land possessions, it was easy to walk around without harassment and recruit other like minded scallywags for upcoming jobs.

Below: A fanciful sketch by artist Howard Pile (dated Nov. 1894) for Harpers Magazine, with fort and windmill also in background [source NYPL]

Kidd was an employee of the Crown, a privateer essentially hired to capture pirates and any foreign vessels that got in England’s way. He was based in New York for many of the same reasons more illicit sea captains were here — opportunities, money and a suitable harbor for his vessel (Kidd’s was called the Adventure Galley).

He came to New York in 1691 and soon married Sarah Oort, a woman with extraordinary bad luck. Her first two husbands had died, one at sea, and after Kidd’s execution, she would then marry a fourth time. William and Sarah would have two daughters who would marry well into New York society despite their father’s notoriety.

Despite his career, Kidd was considered a respectable New York gentleman — much, I imagine, because of his wife’s standing from her prior two marriages. Also, their digs weren’t bad. Although the Kidds owned several properties (again, thanks to Sarah), their primary residence was at the 119 Pearl Street, at the corner of Hanover and Pearl streets, a location which would have been waterfront property back in the day. It was also closely situated to Hanover Square, New York’s retail district and later home of the colony’s first newspapers.

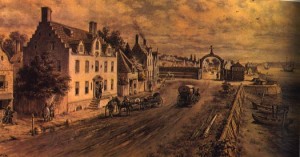

The sizable home was located next to New York’s old wall, a fortification that would be ripped down within the decade and replaced with the street named after it. Kidd’s home is pictured below (i.e. the big white one):

The Kidds home was especially lavish for the time, with “104 ounces of silverware,” a healthy wine cellar and the biggest Turkish carpet in the city. Their wealth would have made them candidates for a pew at the newly built Trinity Church in 1696. Although Kidd provided equipment to help build the church, it appears Kidd himself never worshipped there. (His wife Sarah most likely did.)

Virtually no traces of this era exist in downtown Manhattan today, and the land extension east and the skyscrapers built there eradicate the view the Kidds would have had from their home.

Over a hundred years later, at the same address lived a man named Jean Victor Marie Moreau who would also influence world history: he’s best known as one-time right-hand-man of Napoleon Bonaparte, banished for betrayal in 1804 and sent to America, where he lived for a time at 119 Pearl.

You can read a nice, lengthy piece about Kidd and his New York connections here at Maritime History.