NAME THAT NEIGHBORHOOD Some New York neighborhoods are simply named for their location on a map (East Village, Midtown). Others are given prefabricated designations (SoHo, DUMBO). But a few retain names that link them intimately with their pasts. Other entries in this series can be found here.

NEIGHBORHOOD: Kingsbridge, the Bronx

DUMBO, for Down Under Manhattan Bridge Overpass — a stretch to create an geographic acronym if there ever was one — is not the only neighborhood influenced by a bridge which passes by, through, or over it. It might be the most obvious thing I’ve ever typed, but the neighborhood of Kingsbridge in the Bronx is named for an actual bridge, and the King’s Bridge at that.

The Spuyten Duyvil creek, that short, narrow span of water that separated the far north edge of Manhattan from the west side of the Bronx, has vexed travelers for hundreds of years, due to choppy waters and devilish legends. One translation of its name has traditionally been ‘Devil’s Spout’. Folklore sent Anthony Van Corlaer to his death here. (Listen to last year’s Haunted Tales podcast for more information.)

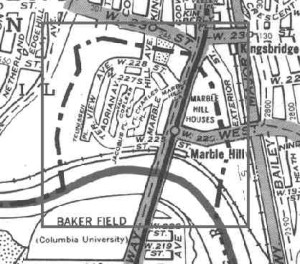

In the past 150 years, the course of this waterway has been re-routed, shut off and

landfilled to

accommodate needs of Harlem River shipping traffic. In fact the neighborhood of Marble Hill, once a part of Manhattan island, has been affixed to the Bronx by drilling a canal though its southern part (in 1895), then filling in the

Spuyten Duyvil to its north (in 1914). This disembodied nub of Manhattan is still administratively considered part of the island.

(Forgotten New York has a wonderful write-up explaining it all. Picture below is from there; the dotted line is where the Spuyven Duyvil once flowed. The solid line is the Harlem River.)

But it’s not Marble Hill we’re looking at here, but rather the neighborhood to its east, Kingsbridge. Way before the Spuyten Duyvil was filled in, the creek posed a challenge for early Dutch farmers wishing to transport their wares into the city markets. However it was narrower than trying to attempt a crossing of the far-broader Harlem, and many farmers used their own boats to get across.

But it’s not Marble Hill we’re looking at here, but rather the neighborhood to its east, Kingsbridge. Way before the Spuyten Duyvil was filled in, the creek posed a challenge for early Dutch farmers wishing to transport their wares into the city markets. However it was narrower than trying to attempt a crossing of the far-broader Harlem, and many farmers used their own boats to get across.

The earlier inhabitants of the land, the

Lenape, simply used canoes when they wished to pass across it; it was at this spot that a well-trodden Indian trail led into the wilderness beyond. By the time of the Dutch, this path had been turned into a workable road, the Upper Trail Road and later the Boston Post Road, which led into New York to the south.

In 1669, in those tentative years of England’s early occupation of the former New Netherland colony, one enterprising Dutch farmer Johannes Verveelen set up a pay ferry service, at the area of the former creek today situated at 231st Street and Broadway — both to serve those who didn’t have their own vessels and to monetize those who had previously preferred their own. This would be fine for awhile, until greater number of travelers to and from New York on the post road commanded that a more permanent solution be found.

Enter wealthy adventurer and servant to the crown

Frederick Philipse. He was actually born in Amsterdam, a slave trader who married into money, came to the New York colony and acquired an estate (or rather, “hunting ground”) encompassing land between the

Spuyten Duyvil creek and the

Croton River further upstate. He built a lavish home here with breathtaking views of the Hudson.

This land once had been owned by

Lenape and farmed by Dutch farmers; now it was part of a wealthy lord’s estate, part of a vast property that would later become the western Bronx and Yonkers. Of course, in the southern part of his estate, there was that pesky road that abutted his property, heavily

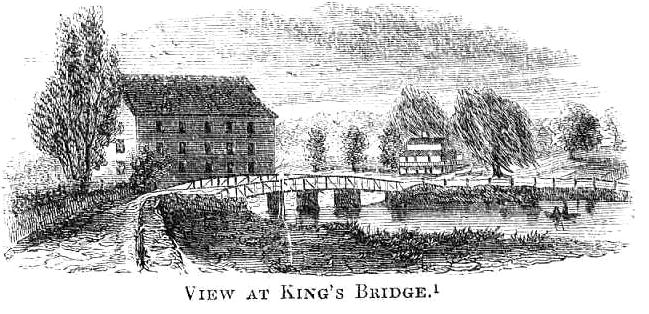

trafficed with people crossing at the creek. No matter. He built a bridge — the King’s Bridge as it was “

established by royal grant” — and charged a fee, payable to the crown.

Philipse’s toll bridge can be seen as a physical representation of the later unrest between England and the colonies. Philipse and his descendants were faithful to the English; his great-grandson would still own the property during the Revolutionary War and would flee when the British were kicked out in 1783.

In the meantime, a mild form of protest was being displayed by neighboring farmers Benjamin Palmer and Jacob

Dyckman, who build the aptly named wooden-plank Free Bridge in 1758, at around 226

th and Broadway. This rebellion was celebrated with

a wild feast, an ox roast, “thousands from the city and country …. rejoiced greatly.” Of course,

Dyckman wasn’t totally altruistic, I suppose; sitting next to the bridge was the family owned

Hyatt Tavern.

Dyckman’s bridge was burned down by British soldiers, but they left the tavern still standing.

As for the King’s Bridge, it too was destroyed — by Washington’s forces, as they fled in 1776 — but was rebuilt after the war. The community of that developed around King’s Bridge, losing the space and the apostrophe, was officially part of Yonkers until the city of New York annexed it in 1874, years before the creation of the Bronx borough.

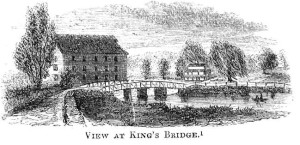

Below: The bridge as it looked in 1856

But it’s not Marble Hill we’re looking at here, but rather the neighborhood to its east, Kingsbridge. Way before the Spuyten Duyvil was filled in, the creek posed a challenge for early Dutch farmers wishing to transport their wares into the city markets. However it was narrower than trying to attempt a crossing of the far-broader Harlem, and many farmers used their own boats to get across.

But it’s not Marble Hill we’re looking at here, but rather the neighborhood to its east, Kingsbridge. Way before the Spuyten Duyvil was filled in, the creek posed a challenge for early Dutch farmers wishing to transport their wares into the city markets. However it was narrower than trying to attempt a crossing of the far-broader Harlem, and many farmers used their own boats to get across.

3 replies on “What’s in a name? In Kingsbridge’s case, a New York first”

Thanks for the Bronx love!

Do any photos exist of the former “Old Bridge Tavern” that was located on the corner of 230th Street and Kingsbridge Ave?

There is a strong likelyhood that nothing remains of the old Kingsbridge because when it was infilled, the wood planks were removed and replaced with cobble. It’s probable they removed everything except the stone piers. They would have needed to fill under the bridge. In any case, any wood left behind would have rotted away by now.