THE FINAL PART UPDATED BELOW – THE FUTURE CITY

See map below for all the locations mentioned in this story

I’m splitting the second half of this series off into a separate posting for easier navigation. Please see the post below this one for the introduction and entries 1 through 50.

————————————————————————-

PART SIX: SUBWAY CITY

51 Flatiron Building (Manhattan)

At the start of the new century, a lust for building tall — now anchored in technologies like steel-beam construction and the invention of the elevator — firmly possessed the world. Before 1890, the tallest building in Manhattan had been a church; in the buildup to 1900, three other took the title, of which only one (the Park Row building) still survives. The Flatiron (1902) was never New York’s tallest, but it was — and still is — it’s most graceful. Chicago’s most famous architect Daniel Burnham took on the challenge of creating a 22-storey, stretched Italian Renaissance office building on a odd triangular sliver of land. The resulting structure (through its near-infinite reproduction on postcards) would almost become a brand representing the nostalgia of New York’s glory days.

52 Sherman Square Subway Station (Manhattan)

In the 19th Century, mass transit meant trains and trolleys, both limited and costly means of transportation always fated to mar the landscape. But New York in the 1900s was in the throes of a new aesthetic: the City Beautiful movement. So in that respect, the introduction of the subway (first opened in 1904) wasn’t just a convenience or a technological marvel. It allowed for the slow elimination of ugliness.

Evidence of this remains in one of the last original subway stations still existing, the entrance for the original Interborough Rapid Transit Company station sitting at Sherman Square on the Upper West Side. Here, the past meets the future, Beaux-Arts trappings for a new form of transportation.

ALSO: Built the same year, the subway entrance at Bowling Green near Battery Park is smaller. Opened in 1905, it wouldn’t be used for Brooklyn traffic until a few years later. The station today still features some unused platforms.

53 Haupt Conservatory (Bronx)

The 1900s was a decade of gigantic public endeavors. The opening of the subway allowed for new projects to be built further afield. And since there was no room in Manhattan anyway, the immediate benefactor were the two boroughs most closely connected by new subway track that decade — Brooklyn and the Bronx.

Both the Bronx Zoo and the New York Botanical Gardens had been opened in the Bronx shortly after the five-borough consolidation in 1898 and would expand greatly in the new century. The Enid A. Haupt Conservatory, completed in 1902, reflects the park’s nod to Victorian era formality, where the rich friends of the garden’s creators could feel at home and the general public could be wowed with a world-class collection of flora.

54 Andrew Carnegie Mansion (Manhattan)

And the upper class didn’t have to travel quite as far to get there. Over the decades, a cluster of great mansions had been floating up Fifth Avenue. In lower Fifth Avenue neighborhoods, the old mansions would be ripped down to make apartment buildings (such as those below 14th Street) hotels and department stores. But the richest families were now installed along Central Park, with Andrew Carnegie throwing down the gauntlet at the most northern locale yet, a monster 91st Street estate, built in 1901.

The 64-room mansion enjoyed “such state-of-the-art features as a water filter system, the first residential elevator, and a rather sophisticated ventilation system akin to an early form of central heating and cooling.” Today, the palatial space houses the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum.

55 Macy’s Department Store (Manhattan)

Retail and entertainment also witnessed a slow migration north, and in that thrust towards mid-Manhattan, the area around one particular elevated train stop — Herald Square — soon became the busiest shopping point in the city. Macy’s, moving from the heart of old Ladies Mile, was not the first department store to lay a claim in Herald Square, but its choice corner location (opening in 1902), reputation for innovative new products and clever promotional opportunities (including a certain yearly parade) made the Straus family business the unofficial gateway to the new Midtown.

courtesy Times Square NYC

courtesy Times Square NYC

56 New Amsterdam Theater (Manhattan)

Entertainment venues were making a similar trek. Theater producers had already transformed the area around Broadway and 42nd Street into the unofficial new theater district when two members of the powerful Theatrical Syndicate opened the New Amsterdam in November 1903. It became one of Broadway’s most successful theaters, hosting the first few Ziegfeld Follies and many of the biggest stars of the pre-film days. It’s one of the few survivors of the Great White Way, a critical stage at the center of 20th century American entertainment. After some sorry days as a movie house, Disney rescued the decrepit house and its renovation became a key part of the ‘clean up’ and revitalization of 42nd Street in the late 1990s.

57 One Times Square (Manhattan)

Opening night crowds at the New Amsterdam could see the silhouette of a new tower rising just to the west, the new home (1905) for one of the city’s most influential newspapers, the New York Times. They only used it for a few years; its significance lies in its superficial qualities. It’s one of the first skyscrapers built over a subway line (with a station constructed right underneath it), and its surfaces were soon covered with electronic bulletin boards and news tickers broadcasting breaking news. An embodiment of the neon-electric revolution that took over the city, it’s no surprise that the most illustrious light show of all — New York’s annual New Years Eve celebration — debuted on its rooftop in 1907.

58 New York Stock Exchange (Manhattan)

It’s remarkable that so many structures that define classical notions of New York City are from this slender period (1898-1910). The prior decade had experienced a devastating depression, the result of banking and railroad financing catastrophes leading to the Panic of 1893. By the new century, America had recovered and then some.

Even Wall Street, one of the sources of the meltdown, benefited from the upswing, with a dazzling new home for the New York Stock Exchange (1903) by the master of neo-classical architecture George Post. The fate of America’s financial future runs through this building’s trading floor. Wealth is bred here, as is misery — namely recessions and depressions, including that Great one, on October 29, 1929 (aka Black Tuesday).

59 New York Police Headquarters (Manhattan)

The shenanigans of corrupt men weren’t relegated to the moguls. The elegant 1909-10 headquarters built for the New York Police Department may have been a way to shake off the force’s shaky reputation for being too pliable to corrupt political winds. In the last decade, the Lexow Committee exposed widespread malfeasance, leading to the installment of police reformer Theodore Roosevelt as new commissioner. With its old boss now in the White House — and the force now comprising officers for all five boroughs — they were given a lavish new home on Centre Street. They stayed until 1973; the building was later converted into luxury apartments, popular with supermodels in the 1990s.

60 Battery Maritime Building (Manhattan)

The Staten Island Ferry has always been a crucial transportation hub for New Yorkers, the only way most Staten Islanders ever commute into Manhattan, even today. The brand new terminal leaves no trace of its history, but the building next to it, the lumbering green Battery Maritime Building (1907) gives you some idea of how the earlier terminal might have looked and operated. And luckily, after years of abuse, the terminal is open for business as a ferry terminal for Governor’s Island and its future may hold some rather extravagant twists.

61 Brooklyn Academy of Music (Brooklyn)

There were fears by those critical of consolidation that any borough not named Manhattan would lose their cultural vitality, becoming neglected suburbs. The criticism was muted the day that the new hall for the Brooklyn Academy of Music opened in 1908, replacing their old home which had been destroyed in a blaze five years earlier. BAM remains Brooklyn’s central cultural organization. Everyone from Enrico Caruso to Nirvana has played here.

62 Seward Park Library (Manhattan)

Despite the best efforts of cultural organizations and charitable endeavors, the residents of neighborhoods like the Lower East Side still did not have access to many basic city services. The city was get a grand central library in 1911 (built by Carrere and Hastings), but it would be smaller community libraries that would have greater effect over the daily lives of New Yorkers.

Andrew Carnegie, in his later years a philanthropist, built hundreds of libraries around the country, often in neighborhoods most in need of them, and New York was recipient of dozens throughout the city. The one at Seward Park, from 1909, is one of the city’s oldest, replacing an older structure with a virtually flawless Beaux-Arts gem facing into the park — which, as a two-for-one for history lovers, houses the city’s oldest municipal playground.

And yes, the Seward Park area desperately needed a library, especially one filled with newspapers and books in the foreign languages of the neighborhood’s occupants. In 1913, it had the highest circulation of any library in the city.

ALSO: Right across the street, the Jewish Forward newspaper would build a stunning new headquarters in 1913 where it would remain for six decades. Or if you’re looking for a more regal library, turn your attention uptown to the book repository built for J.P. Morgan in 1906 which actually outlived the owner’s mansion next door.

FOR MORE INFORMATION: Listen to our podcasts on the Flatiron Building, Macy’s Department Store, the Ziegfeld Follies, One Times Square, the New York Stock Exchange and the New York Public Library

————————————————————————-

PART SEVEN: METROPOLIS

The ugly story behind the plain, upper floors of the Asch Building

63 Asch Building (Manhattan)

There are two buildings from the 1910s that hold a very practical importance to the daily lives of New Yorkers still today — places that aren’t necessarily classics in any aesthetic sense, but serve as object lessons to a growing city.

Today known as NYU’s Brown Building of Science (at Greene and Washington Place, off Washington Square), the Asch Building held the sweatshop factory of the Triangle Shirtwaist company on its top three floors. On March 25th, 1911, a fire sparked in a bag of rags quickly built into an unstoppable inferno, trapping hundreds of workers, many who fatally leapt to the sidewalk below. The 146 dead, mostly women newly immigrated to the United States, were mourned by the city, and tragedy forced an improvement in radical new building fire and safety codes.

64 Equitable Building (Manhattan) The other ‘lesson’ represents something of a crisis averted — a new home at 120 Broadway for a life insurance company (who was moving here because a fire had destroyed their last office) that represents a metaphorical slamming of the brakes, the moment when New Yorkers realized that they actually had to live in a city of skyscrapers. Maybe new skyscrapers shouldn’t all be block-length, 38-story uninterrupted slabs that blocked out the light.

The other ‘lesson’ represents something of a crisis averted — a new home at 120 Broadway for a life insurance company (who was moving here because a fire had destroyed their last office) that represents a metaphorical slamming of the brakes, the moment when New Yorkers realized that they actually had to live in a city of skyscrapers. Maybe new skyscrapers shouldn’t all be block-length, 38-story uninterrupted slabs that blocked out the light.

The Equitable colossus (at left,1915) sent a shiver through the spine of the city. Within a year, new zoning laws would dictate how future skyscrapers should be made — beginning an era of ‘wedding cake’ setbacks and the birth of innovation in the New York City skyline.

65 Woolworth Building (Manhattan)

The new headquarters for Frank Woolworth’s retail chain was completed in 1913, three years before the zoning laws. Yet it was rapturously received by New Yorkers, both for its classic beauty (a Cass Gilbert original) and iconic stature, for it was now the tallest building in the world.

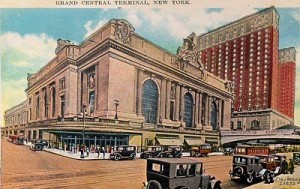

66 Grand Central (Manhattan)

I’ve stated in our podcast for Grand Central Terminal that I thought this was New York’s most important building (1913), and I stand by that. Not only is it essential as a transportation hub for millions of travelers, but its dramatic rescue from developers wanting to rip it down in the 1970s went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, empowering the New York Landmarks Preservation Commission and saving countless other buildings in the process.

And forget that it’s New York’s greatest example of Beaux-Arts architecture! Grand Central’s key contribution to the city rolls out in front of it northward; sinking New York Central Railroad’s tracks under the ground created the midtown section of Park Avenue, soon to become one of the most expensive streets in America.

67 Apollo Theater (Manhattan)

Next to perhaps only the long-gone Savoy Ballroom, the Apollo Theater is the largest venue most associated with the Harlem Renaissance, a cultural explosion of black writers, artists and musicians which electrified the Roaring ’20s and beyond, the product of one of the city’s most significant population shifts.

Harlem was a neighborhood in flux in the 1910s, displayed nicely within the Apollo’s own history. The theater opened as a burlesque house for white audiences in 1914, although by the ’20s Harlem was fast becoming a mecca for new African-Americans in the city. The neighborhood evolved, but many of its closed-minded businesses paid no heed. Apollo wouldn’t reopen for black audiences until 1934 — missing much of the early musical talent of this American Renaissance, but launching the careers of many more stars (Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday, James Brown).

68 Kaufman Astoria Studios (Queens)

Cinema, probably more than any other medium, has helped form the exotic allure of New York City. But there was a period when New York’s entertainment venues — its vaudeville and flashy Broadway stages — feared the coming of movies, a medium that would eventually bleed from them their audiences.

For a brief time before the era of motion picture talkies, New York’s film cred wasn’t merely as a city of plush cinemas. It helped make most of the pictures too. Adolph Zukor’s Famous Players Film Company (a precursor to Paramount Pictures) opened a movie studio in Queens in 1920, one of several major film companies based in the New York metropolitan area. Today, as Kaufman Astoria Studios, it still produces entertainment, though mostly for television.

ALSO: Zukor had a second space in Chelsea at West 26th Street which also still functions as a soundstage and rehearsal studio (Chelsea Studios).

69 Nam Wah Tea Parlor (Manhattan)

This tiny, beaten-up shop at the hook of Doyers Street is a real survivor, a window into the early days of Chinese life in New York. The slums of Five Points had been paved into a park, and municipal buildings were soon to be built to the west. But just north and east of the former slum were the homes and businesses of thousands of new residents — Italians and a small but growing number of Chinese.

Reportedly open since 1920, Nam Wah would have been witness to some remarkable history on its street — to the shadowy speakeasy across the street where Irving Berlin and Al Jolson regularly performed; hatchet-wielding tongs wars that gave this crooked street the nickname the ‘Bloody Angle’.

70 Colonial Court, Sunnyside Gardens (Queens)

We know the 1920s as the Jazz Age, of Prohibition, flappers, gangsters and Times Square. But in the course of New York City history, the big story of the decade was the population explosion in Queens. With the construction of the Queensboro Bridge in 1909, the door were thrown open to a virtually untouched area of the city.

Between 1920 and 1930, the population more than doubled. Making this possible were experimental new housing projects like Sunnyside Gardens, an extension of the British ‘garden city’ movement, with affordable apartment rentals scattered around large, well-kept outdoor spaces. Colonial Court (1924) were the first buildings erected and were so marvelous for the day that pioneering urban theorist Lewis Mumford immediately moved in.

ALSO: Manhattan also received its share of this new, fleeting style of apartment complexes, as evidenced by the playful towers in Tudor City on midtown’s east side, beckoning new residents with promise of “tulip gardens, small golf courses, and private parks.”

71 Williamsburgh Savings Bank Tower (Brooklyn) The skyscraper craze, like a floating seed gone astray, landed in the middle of Brooklyn and spawned a home for a bank steadfastly keeping that H in the name of Williamsburgh. It stood out like a beautifully sore thumb for other reasons: built in 1927, it was one of the first large examples of art deco architecture in the city. And its fabulous interior, gold and blue and framed in signs of the Zodiac, rivals almost anything in Manhattan.

The skyscraper craze, like a floating seed gone astray, landed in the middle of Brooklyn and spawned a home for a bank steadfastly keeping that H in the name of Williamsburgh. It stood out like a beautifully sore thumb for other reasons: built in 1927, it was one of the first large examples of art deco architecture in the city. And its fabulous interior, gold and blue and framed in signs of the Zodiac, rivals almost anything in Manhattan.

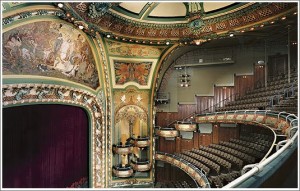

72 Loews Paradise Theater (Bronx)

Yes, consolidation was truly proving its point: the city was expanding from all sides. In the Bronx, that growth is best viewed from the Grand Concourse, a wide, Parisian style boulevard that marches up through the center of the borough. Along it sprung luxury apartment buildings, tony businesses and, in 1923, even Yankee Stadium.

The glamour of the boulevard’s early days can best be seen at its finest existing movie palace the Paradise Theater (1929), recently renovated to match its former glory. How this building managed to survive the 1970s and 80s, I’ll never know.

ALSO: A parallel movie house, St. George Theater in Staten Island (1928) was rare not for its location and its dazzling, gilded interiors, but for the fact that it was built by an independent theatrical producer, during the days when film companies and theatrical syndicates made their own venues.

Below: The Paradise Theater, the Bronx

73 Waldorf-Astoria Hotel (Manhattan)

The greatest hotels in New York City have been associated with the Astor family, including the old Astor House near City Hall and the original Waldorf-Astoria, a product of familial rivalry that set the standard for elegance and attracted New York’s wealthy classes like a flame.

The Waldorf-Astoria on Park Avenue is associated with the family in name only, but its reputation as New York’s most famous hotel, while faded, remains unblemished. FYI, they’ve recently decided to hyphenate themselves with a ‘=’ today.

74 Chrysler Building and

75 Empire State Building (Manhattan)

The Depression hit in October 1929, an economic apocalypse that threatened to slow the momentum of New York’s growth. Curiously, at that very moment, the two greatest buildings in New York City were just rising into the sky.

The Chrysler Building was the victor of a race between the car mogul William Chrysler and the Bank of America, who was racing to make the world’s tallest building down at 40 Wall Street. While the downtown building was finished first, it was dwarfed (in both height and appearance) when William Van Alen’s art deco, automobile-inspired masterpiece lifted up its silver spire in October 1929.

Several blocks away, work began on a tower to surpass Alen’s, in a pit that had once been the original Waldorf-Astoria. It rapidly rose into the sky, completed in May 1931 — and pretty much stayed empty. New York had its Empire State Building, the structure which would define it for generations, and for years, all people could do it look at it and see a monumental failure. Few associate this tourist mecca with underachievement today. But its current might is tinged with grief; on September 11, 2001, it returned to being New York’s tallest building.

Picture above by Andreas Feininger, Sept 1946 (courtesy Life Google Images)

For more information: listen to our podcasts on the Triangle Factory Fire, the Woolworth Building, Grand Central, the Apollo Theater, the Astor family, and the Chrysler Building.

————————————————————————-

PART EIGHT: THE MODERN CITY

Courtesy Liberty Stone

Courtesy Liberty Stone

76 Jacob Riis Bathhouse (Queens)

Although he wouldn’t be named parks commissioner by mayor Fiorello LaGuardia until 1934, Robert Moses was already remaking areas of New York City as a member of Governor Al Smith’s state parks team. Nowhere as spectacular as his work at Jones Beach, Moses’ Jacob Riis Park — named for the journalist and social reformer — brought the verisimilitude of beach life to this former naval base on the Rockaway Peninsula.

The classic art-deco bathhouse (1932) reflects Moses’ early attention to beautiful detail, a proclivity that would fade over the years. Setting nearby is another special touch of the powerful commissioner — a massive parking lot.

77 Robert Moses Administration Building (Randall’s Island)

This nice but fairly plain little building on Randall’s Island belies its importance in the history of New York. It’s from here, in the shadow of his triumphant Triborough Bridge (1936), that Robert Moses conducted the development of hundreds of new projects — parks, highways and housing. As Robert Caro famously summed it up, “Moses’ decision to built his main office there was, intentionally or not, symbolic of his independence of the city.”

78 RCA Building (Manhattan) Before the FDR’s New Deal programs and the adrenaline of Moses, virtually the only game in town during the Great Depression was the construction of Rockefeller Center. Junior’s multi-block complex in midtown Manhattan was a true risk, opening new retail and office space when the city’s pre-existing spaces were going empty.

Before the FDR’s New Deal programs and the adrenaline of Moses, virtually the only game in town during the Great Depression was the construction of Rockefeller Center. Junior’s multi-block complex in midtown Manhattan was a true risk, opening new retail and office space when the city’s pre-existing spaces were going empty.

30 Rock, the former RCA Building, became midtown’s center of gravity when it was completed in 1933. Within a few years, both it and the other Rockefeller Center offices were filled to capacity.

79 Tavern on the Green (Manhattan)

If you’re looking for a defining building that embodies Moses’ park philosophy, you’ll find it in this oft-troubled restaurant in Central Park. Olmsted and Vaux’s vision of natural respite seemed old-fashioned to Moses, who thought parks should provide venues, playgrounds and sporting courts. Tavern-on-the-Green (1934) was originally created as an ‘affordable’ dining alternative for the middle class. To build it, Moses threw the sheep (actual sheep) out of nearby Sheep Meadow and transformed their sheepfold into this privately-owned restaurant. Later, in the 1950s, when Moses tried to expand its parking lot by paving over a playground, the public revolted.

Below: Tavern on the Green in 1934

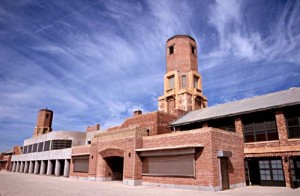

80 Arthur Avenue Retail Market (Bronx)

Speaking of sheep, the land below Arthur Avenue’s busy market was also once a sheep’s grazing meadow. (It’s also on the former estate of the Lorillard tobacco family, see No. 22.) When Mayor LaGuardia dictated that unregulated pushcart salesmen, the lifeblood of many ethnic neighborhoods, move their wares indoors, he commissioned indoor markets throughout the city, including this one (1940) in what was becoming a booming new Italian neighborhood.

Inside, you’ll find one of Arthur Avenue’s most famous vendors, Mike’s Original Deli, which moved here in the early ’50s and never left.

ALSO: The same strategy was applied to La Marqueta (1936), which provided for the neighborhood’s growing Latino and Puerto Rican communities. A shadow of its former self today, the market at its height housed stalls for over 500 merchants.

81 New York City Building (Queens)

Flushing Meadows-Corona Park’s only surviving structure from both the 1939-40 and 1964-5 World’s Fairs, this home to the Queens Museum today (1939) holds the Panorama, a miniature replica of the city of New York. For a short time, the United Nations even met here. Moses had hoped that the international delegation would choose Flushing Meadows Park, one of his closest pet projects, as their permanent home…..

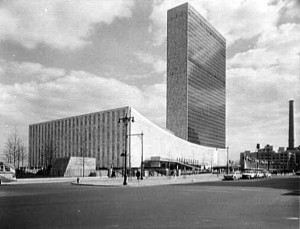

82 United Nations Building (Manhattan)

…but they recoiled at that thought, choosing instead this customized property on the east side of Manhattan (1950). The U.N. Headquarters is globally significant, of course, but its an innovative architectural marvel as well, the first of dozens of towers in the glass-curtained International Style. For better or worse, it keeps New York City front and center as a focal point for international politics.

83 Seagram Building (Manhattan) That modern style would be used and abused for the next two decades, as modern commerce embraced tall, boxy high-rises as the critical form of construction. The cleanest example is Mie Van Der Rohe’s graceful black monolith (1958), powerful and utterly lacking in ornamentation. The key to the building, constructed for the alcoholic distiller, is the large public plaza in front of it, reinterpreting the old zoning laws to such an extent that the laws themselves were changed, in 1961.

That modern style would be used and abused for the next two decades, as modern commerce embraced tall, boxy high-rises as the critical form of construction. The cleanest example is Mie Van Der Rohe’s graceful black monolith (1958), powerful and utterly lacking in ornamentation. The key to the building, constructed for the alcoholic distiller, is the large public plaza in front of it, reinterpreting the old zoning laws to such an extent that the laws themselves were changed, in 1961.

As lovely as the Seagram Building is — and its companion across the street, the Lever House, from 1952 — those zoning alterations have doomed Midtown to a host of ugly, darkened ‘communal spaces’ and glassed-in plazas.

84 La Luz Del Mundo Church (Brooklyn)

Williamsburg, a former industrial heart of Brooklyn, saw a unusual population shift after World War II, with white residents moving out to be replaced by Puerto Ricans families living next to a tightknit Hasidic enclaves. As New York became a true melting pot after the war, divergent communities grew used to living side by side.

Many 19th century buildings were repurposed by this modern mixture. One hundred years after Congregationalists worshiped here at this brownstone chapel, the Spanish Penecostal congregation La Luz Del Mundo moved in (1955).

Courtesy MAS

85 Trans World Flight Center (Queens)

Idlewild Airport represented the future of flight when it was proposed in the late 1940s, utilizing a single, gigantic terminal that would ease traffic at the beleaguered LaGuardia Airport. Flash forward 20 years — the completed airport is now named John F. Kennedy International Airport, LaGuardia is still busy, and instead of one terminal, there were several, of innovative modern design. The best was made for TWA (1962) by Eero Saarinen, reflecting an almost innocent outlook towards the possibility of air travel, an archetype of public design. Reflect on the halcyon days of commercial flight as you’re sitting at JFK today, waiting for your delayed flight.

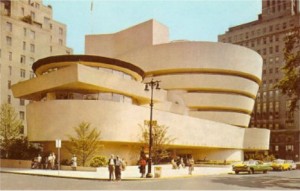

86 Guggenheim Museum (Manhattan)

Presaging the work of modern artists who would define the city’s cultural tastes in the 1960s, aging architect Frank Lloyd Wright displayed a goofy flourish with the construction of the Guggenheim Museum (1959).

87 Park West Village (Manhattan)

This cluster of ordinary-looking apartment dwellings (1960) sit on top of the former slum of Manhattantown — an unspectacular place if not for the shady machinations of developers Caspert and Company. Empowered by the federal government’s Title 1 housing act, Moses sanctioned Carpert in 1947 to clear away slums and develop new apartments. Instead, the land sat there — countless delays — while the developers scooped up the rent. The press had a field day, tarnishing Moses’ public image.

The land was eventually transferred to other developers who built Park West Village — of a gloomy standard that would become commonplace with new dwellings.

ALSO: But for something extraordinary, check out the largest ‘building complex’ on my list, Co-Op City (finished between 1968-71), the largest ‘building complex’ on my list. For despite being surrounded by highways, despite housing available for 50,000 residents, the city within a city remains virtually remote, with no convenient subway access.

88 Stonewall Bar (Manhattan)

Luckily, this was the 1960s, and communities protested, students protested, everybody protested. Sometimes, people in power even listened. But one revolt decidedly not on City Hall’s radar was the riots outside Stonewall Bar (1969) between police on a routine shutdown of West Village gay bars and a clientele (and rabble from the park across the street) reaching their breaking point. Within a year, the events at this shoddy, mafia-run bar had united a community and jump-started the gay movement.

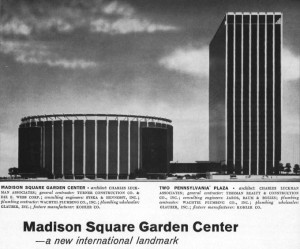

89 Madison Square Garden (Manhattan)

*Sigh* And finally we get to the enormous bundt cake pan that calls itself Madison Square Garden (1968) after the three prior, spectacular incarnations of the same building. Not disparaging any of the wonderful entertainment that goes on inside, the Garden and the subterranean Penn Station are testaments to a mindset of the 1960s, a short-sighted vision of the future that through its lumbering, brutalist qualities threatened to dynamite any glimmer of livability.

The city is currently figuring out how it wants to transform Penn Station into Moynihan Station using the 1912 James Farley Post Office building across the street, an ironic move that would allow the ‘modern’ train station to slither out of the shadows via an old Beaux-Arts structure similar in form to the building that was demolished to build the Madison Square Garden/Penn Station combo in the first place.

For more information, listen to our podcasts on Randall’s Island, Rockefeller Center, the World’s Fair of 1964-65, the United Nations Headquarters, Freedomland U.S.A., the Guggenheim Museum, Penn Station and Madison Square Garden

————————————————————————-

PART NINE: THE FUTURE CITY

91 Show World Center (Manhattan)

Ah, New York City in the 1970s. People wax nostalgic about it even though nobody in their right mind would take a time machine and return there, except maybe to go to CBGBs. Crime, blackouts, poverty, filth, disco.

But the course that 42nd Street took in the 90s — going from sleazeland to Disneyland — was so dramatic and final that one can’t help be slightly wistful, for that street of lonely marquees, interspersed with poop booths and neon signs for EXOTIC GIRLS. Not the drugs or prostitution, but a street, in the center of Manhattan, that wasn’t so primly cultivated.

Show World Center, right off 42nd on Eighth Avenue, is a holdover from this gritty world, a flashy, trashy video store from 1975 that’s emblematic of Times Square’s days of deterioration, a place that the Times mentions that “burlesque historians say was once a widely imitated model for the industry.”

ALSO: You can find another reflection of Times Square further east, at the TKTS booth, which originally opened in 1973, though the high-tech, staircase-laden revision, which opened two years ago, is a jewel case version of the bombast currently inhabiting the Square today.

92 Queens Center Mall (Queens)

A hundred years before, it was Ladies Miles. In the 1970s, it was shopping malls. New York City generally shuns some of the standardizations of modern America, but with the blooming of larger residential areas, the lure of modern conveniences like fast food restaurants and shopping malls soon infiltrated. New York’s first McDonald’s opened in 1973. That same year, a humongous shopping mall opened in Elmhurst, a staple of suburbia refitted for the big city.

ALSO: Snooty Manhattan would not be immune; the strangely depressing Manhattan Mall opened in 1989.

93 41st Precinct Station aka “Fort Apache” (Bronx)

FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD cried the Daily News in 1975, a rebuff by the federal government to New York City’s financial woes. Buckling at its knees, New York spent years consumed with urban blight, catastrophic crime statistics, an abysmal public image and even a roaming serial killer.

During the blackout of 1977, there was probably no place less safe to be than the South Bronx (although Crown Heights, Brooklyn, might win honorable mention). Construction of the Cross Bronx Expressway, widespread poverty and inadequate resources led to a vast crime wave. The officers at the Bronx 41st Precinct (1086 Simpson Street) personified the city’s remaining shreds of determination to fight back, so much so that it even became a melodramatic Paul Newman film, “Fort Apache, the Bronx.” The cops are gone, but the 1914 structure still stands as a reminder of grimmer times.

94 Jacob Javits Convention Center (Manhattan)

The late 1970s and early 1980s weren’t a watershed age for architecture, but at least it was oftentimes functional as with the Jacob Javits Convention Center (completed 1986), a valiant if unsuccessful attempt to reaffirm New York as the home for big business. In its own modest, boxy way, it recalls the city’s great spaces of old, both the grand (the Crystal Palace) and the unsightly (the New York Coliseum).

95 Trump Tower (Manhattan) Has one building ever typified an entire decade more than this gaudy palace to Donald Trump? Even as the city began picking itself up, its flashiest developer was embodying a greed-is-good mantra in his decision to throw a gold monolith onto Fifth Avenue (1983).

Has one building ever typified an entire decade more than this gaudy palace to Donald Trump? Even as the city began picking itself up, its flashiest developer was embodying a greed-is-good mantra in his decision to throw a gold monolith onto Fifth Avenue (1983).

ALSO: Another tower of wealth, the Citicorp Building becomes the tallest building outside Manhattan (1990).

96 Fresh Kills Methane Treatment Plant (Staten Island)

If you have to point to one thing that symbolized the uneasy relationship between Staten Island and the rest of New York, it would be the former site of the Fresh Kills Landfill, a disastrous Robert Moses idea that turned 2,200 acres of calm, bucolic farmland into the largest garbage dump in the world.

Closed in March 2001, the city has been transforming this toxic site into a future park, a task that will literally take a generation to complete. Industrial structures like the methane treatment plant reform the soil as the former mounds of garbage are transformed into a charming meadow.

97 Deutsche Bank Building (Manhattan) Even as new construction finally rises from the site of the World Trade Center, the terrorist attack still has one more victim to take. The Deutsche Bank Building was heavily damaged by the September 11, 2001 attacks, but, unlike the buildings surrounding it, did not immediately collapse. However it’s been deemed unsalvagable and, after years of delays, is finally in the process of being deconstructed — a couple floors at a time.

Even as new construction finally rises from the site of the World Trade Center, the terrorist attack still has one more victim to take. The Deutsche Bank Building was heavily damaged by the September 11, 2001 attacks, but, unlike the buildings surrounding it, did not immediately collapse. However it’s been deemed unsalvagable and, after years of delays, is finally in the process of being deconstructed — a couple floors at a time.

By next year at this time, the building should be gone. (Barring delays, of which there’s been a few.)

98 The New York Times Building (Manhattan)

The New York skyline welcomed a bevy of new skyscrapers courtesy of the publishing world, just in time for the pending death of that very industry. Conde Nast (2000) stands over Times Square like Anna Wintour staring at a sales rack, and the hive-like Hearst Tower (2006), planted on top of the base of the old building, looks like its crushing it.

But none seem as strangely cursed as the new offices for the New York Times (2007); the newspaper took a loan out on the new building a year after they moved in, and the sleek design by Renzo Piano has encouraged adventurers and nuts alike to climb along the side of it.

99 The Blue Condominum (Manhattan)

The past decade saw many formerly middle- or low-income neighborhoods with the occasional maverick artist enclave in the process of gentrification — from Manhattan’s Lower East Side to Greenpoint in Brooklyn and well beyond. While one effect of this has sometimes been a richer appreciation of local history, some changes stand in bold contrast, as luxury hotels and pre-bust condos sprout up casting shadows and a foreboding sense of takeover.

The Blue Condominium (2006) is representative of architectural hipsterism, a model of strange proportional absurdity; being so blue, it would stand out anywhere, but especially on Norfolk Street, in sight of the Williamsburg Bridge. And yet, in a city that prides itself on structural diversity, where Beaux-Arts and brutalism stand hand in hand, it’s not necessarily a cause for alarm (as long as people can afford to live here).

The new stadium, next to the old, courtesy of umpbump

The new stadium, next to the old, courtesy of umpbump

100 Yankee Stadium (Bronx)

Tradition and consistency are key components to the love of professional sports, and those two forces are at work in the new Yankee Stadium (2009). It’s both a stadium and a theme park to the past. Although the new home for Derek Jeter mirrors trends popping up in other nostalgia-inspired ballparks, it nicely contrasts as an opposite of the Blue building in finding ways to preserve the past and live in the present.

What’s the balance between being false to the spirit of a neighborhood and being so technically exact that it’s like architectural drag? Eh, who cares, let’s play ball!

For more information, check out our podcasts on the New York City Blackout, a short history of Staten Island and the New York Yankees

View History of New York in 100 Buildings in a larger map

1 reply on “A History of New York City in 100 Buildings (Nos. 51-100)”

So many great buildings and landmarks listed here. Thanks for this post.