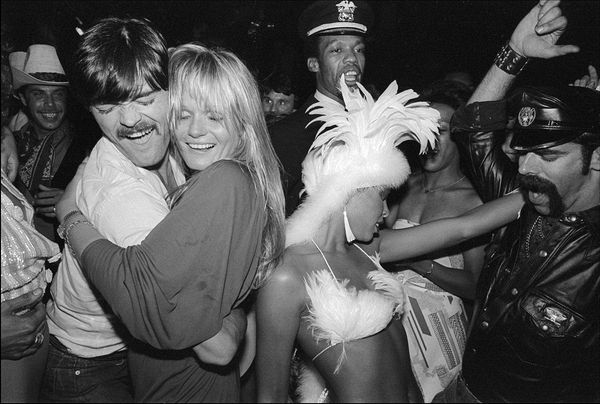

You know it’s a good night at Xenon when you’re drunk on the dance floor, and all of a sudden, the actress Valerie Perrine and the Village People appear (source)

FRIDAY NIGHT FEVER To get you in the mood for the weekend, on occasional Fridays we’ll be featuring an old New York nightlife haunt, from the dance halls of 19th Century Bowery, to the massive warehouse clubs of the mid-1990s. Past entries can be found here.

LOCATION: XenonTimes Square, 43th Street and Broadway, Manhattan

In operation 1978-84

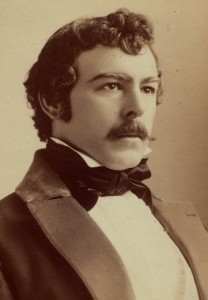

THIS, AT LEFT, IS HENRY MILLER. Clearly this is not the Henry Miller you more popularly know.

THIS, AT LEFT, IS HENRY MILLER. Clearly this is not the Henry Miller you more popularly know.

This Henry Miller would have never produced Tropic of Cancer. But his major contribution to the American stage would bring New Yorkers an iconic work of French cinema, a world famous theatrical revival, and one of the most successful Studio 54 knockoffs ever.

Miller was a minor theatrical star in the age of Sarah Bernhardt, who began dabbling as a director and stage manager at the same time that theater on 42nd Street began to flourish in New York. He became an early, respectable presence; from an early biography: “It was a foregone conclusion that a Henry Miller production must be in the best tradition of the theater.”

His timing was exquisite as well. The Broadway district in the 1910s was in full swing, with excitement at all hours. His patron (and progressive, feminist icon) Elizabeth Milbank Anderson assisted him in opening a stage in 1918 at 124 W. 43rd Street, a prime location near the theaters of Oscar Hammerstein, Klaw & Erlanger and Florenz Ziegfeld. The old New York Times building was half a block away, the nexus for New Years Eve celebrations for over a decade. Across the street rose the Hotel Metropole with its bustling late night antics; a few years earlier, in 1912, you could have stood in Miller’s lot and watched the bloody mob hit of gambler Herman Rosenthal — possibly ordered by New York cop Charlie Becker. (You can hear more about that in our Case Files of the NYPD podcast.)

There were no hits at Henry Miller’s theater, however, not the lucrative kind at least. In fact, the first show, The Fountain of Youth, was an unmitigated flop, opening in April 1918 and closing in May. (“This fountain of youth plays a very slender stream, and even that is of intermittent vigor,” claimed one review.) Famous names played here — George Gershwin, Billie Burke, Helen Hayes — but it wouldn’t be until Noel Coward debuted his scandalous, sex and cocaine-fueled comedy The Vortex in September 1925 that Miller’s theater would see its first in a string of major successes. Miller himself, however, would not enjoy these successes; he died a few months after Coward’s debut, in early 1926.

Below: Henry Miller’s theater, during its glory days. Photo courtesy NYPL

But Henry’s son Gilbert Miller had a knack for theatrical production even greater than his father. For three decades, he ushered countless box office hits through the Henry Miller’s Theatre, including the Tony winning T.S. Eliot play The Cocktail Party starring Alec Guinness. Most notably, Our Town would make its Broadway debut here in February 1938, and in 1957, a young British actress named Angela Lansbury would make her American stage debut here in Hotel Paradiso. Gilbert would win an honorary Tony in the mid-1960s for his contributions to the New York stage.

By then, however, the theater began flirting with a transition that many midtown stages had already made — into a legitimate movie house. Its first foray was also its most memorable, Federico Fellini‘s La Dolce Vita, premiering here in April 1961. The strangeness and theatricality of Fellini’s masterpiece fit the Henry Miller playhouse perfectly, even if the stage itself was technically ill-fitted for movies. The grumpy critic Bosley Crowther was even impressed: “Fellini’s “La Dolce Vita” (“The Sweet Life”), which has been a tremendous hit abroad since its initial presentation in Rome early last year, finally got to its American premire at Henry Miller’s Theatre last night and proved to deserve all the hurrahs and the impressive honors it has received.”

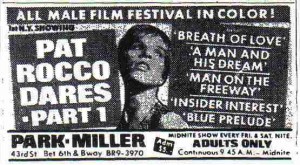

This might have been a harbinger for a fabulous future as an art house, however the theater was instead sold, renamed the Park-Miller, and entered the 1970s as one of Times Square’s most popular porno theaters, specializing in all-male features for gay audiences.

Although Henry Miller was certainly turning in his grave, the theater actually become quite successful, more so than most of Miller’s own productions during his lifetime.

According to author Hilary Radner, “the Park-Miller Theater on 43rd Street grossed in excess of thirty thousand dollars per week in the early 1970s….For a five dollar admission fee, audience members watched a mixed program that included shorts, slides, and a dubbed minifeature, such as Truckers — Men of the Road.” A long way from The Fountain of Youth, indeed!

Below: an advertising glimpse into the theater’s more prurient days

Everything changed in the spring of 1977 with the transformation of an old opera house into the superstar disco spectacular Studio 54, epitomizing the notion of nightlife as a headline-grabbing celebrity wonderland. One night at 54, music manager Howard Stein met Swiss restaurateur Peppo Vanini (the ex of actress Victoria Tennant), and the two cooked up a scheme to match the club’s glamour in another midtown location.

Stein purchased the old porn theater and remade it into the discotheque Xenon, although Xerox might have been a better name, for it adhered closely to the Studio 54 formula of flashy nights, big celebrities and kitschy showmanship (cannons with colored feathers, a neon X above the dance floor).

Being just slightly lesser a club than 54, you actually did stand a chance of getting in if you happened not to be a bold-faced somebody. But Stein would occasionally stand at the door himself “weeding out the detested middle class from the very rich and the colorful poor,” according to a New York Magazine profile.

Below: the club, during the day, in the 1970s:

Still, Xenon had its day, and on a typical hot summer night in 1979 or 1980 you might stumble into private parties hosted by Michael Jackson, Woody Allen, Lauren Bacall, Ben Vereen, or Pele. Inside you might hear deejay Jellybean Benitez.

Although people often stripped down to bikinis on the dance floor, you had fewer naked Grace Jones moments; Xenon “combined the craziness of Studio 54 with the comfort of Regine’s” according to one source, Regine’s being the more elegant nightclub entree owned by French chanteuse Régine Zylberberg.

With the end of disco came the end of Xenon, in 1984, and a brief attempt at turning the space into a rock ‘n’ roll venue called SHOUT! It lay mostly dormant, hosting temporary parties, until the early 1990s, when in a flash of inspiration, the Roundabout Theatre renovated the worn, abused little stage, combining all eras of its history to transform it into the Kit Kat Club, a cabaret venue fit to re-stage, naturally, Cabaret. That version, starring Alan Cumming and the late, wonderful Natasha Richardson, would go on to win the Tony for Best Musical Revival in 1998. Incidentally, that same year, a devastating construction crane accident next door closed the block for weeks, and Cabaret would be forced to move uptown — to the former Studio 54.

Suddenly, all its prior incarnations seemed to enjoin to create its most successful reinvention yet. After Cabaret left, the hot off-Broadway show Urinetown moved in; that bawdy musical took three Tonys in 2003.

And then, they demolished it.

Saving the landmarked front exterior — with Henry’s name emblazoned along the top — the rest of the building was scrapped in a massive construction project that eventually put the Conde Nast Building to its west side and the Bank of America building to its north, to which a new theater was attached, using that old exterior and renamed the Stephen Sondheim Theatre. In the fine tradition of Henry Miller himself, the stage has features two shows — a revival of Bye Bye Birdie, and the Dame Edna musical All About Me — both flops.

For some great recollections of the glory days of Xenon, check out the website Disco Music. Featuring one commenter who says: “There’ll never be a club like it again. Pinball machines would drop out of the neon heavens and land next to dancers gyrating to ‘Funky Town’ by Lipps. Not to mention the fake snow (clearly an homage to the abundant cocaine passing through nostrils by one and all) that dropped on you, sticking to your favorite nylon shirt.”

2 replies on “Xenon and the strange journey of a Broadway theater: Noel Coward, Fellini, porn, disco, ‘Cabaret’, Dame Edna”

This is a fantastic post! Thank you so much you guys are really great. This theatre is a capsule of Times Square New York in the 20th century. Keep them coming!

”

Below: the club, during the day, in the 1970s:”

I don’t agree that

http://www.songwriting.net/blog/topic/lyrics