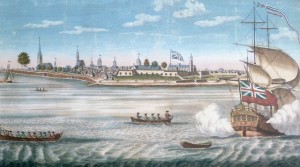

The harbor in 1730, with a view of New York’s Fort George by the engraver John Carwitham

The harbor in 1730, with a view of New York’s Fort George by the engraver John Carwitham

It was 270 years ago this week that a truly foul period in New York history began, starting with a host of fires sprouting up throughout lower Manhattan and ending with several black residents of the city hanged and accused of treason, a reign of terror known as the Conspiracy of 1741 (or the Negro Plot of 1741), a hellish inquisition fueled by hysteria, racism and rumor.

Believing that local slave and freed blacks — along with white ‘traitor’ conspirators — had conspired to wreck havoc in the city, the authorities gathered up suspects and accused them of crimes based on scant evidence. In the end, over 30 people were executed for their part in this supposed ‘conspiracy’. Modern historians are unsure such a plot existed at all, and if it had, most of the executed would still have been innocent of wrong-doing.

This violence, which kept the city in a grip of heightened suspicion for most of the spring of 1741, have often been called New York’s version of the Salem witch trials.

For a rich description of these events and some measured speculation to its cause, I direct you to Jill Lepore’s excellent book from a few years ago New York Burning, one of the few books that turned on my enthusiasm for New York City history.

The reason I’m bringing this up today is that St. Patrick’s Day — or rather, the Catholic Feast of St. Patrick from which the holiday derives — actually figures into the story. Just like the modern holiday, it appears that both Catholics and non-Catholics took part in the March 17th celebration, and in particular, the imbibing. According to ‘Gotham’ by Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, soldiers at their posts at Fort George on March 18th were “recuperating in their barracks from their hearty celebration” the night before. Essentially, an epidemic of hangovers.

As a result, the fort was scantily patrolled that morning. As guards slept the morning away, unknown arsonists stole into the fort and set fire to several buildings inside, including the old governor’s house, once the home of Peter Stuyvesant (who, trust me, never would have allowed this to happen). The blaze quickly spread to the chapel , the soldiers barracks, and even to buildings outside the fort perimeter. It might have blossomed into a raging inferno that would have consumed the city had it not rained and doused the blaze from spreading further. (Thank you St. Pats!)

Had the men at Fort George been more alert, perhaps they would have identified the mysterious culprit. Not only would it have prevented the fire, it might have clamped down the later hysteria and prevented further arson from occurring throughout the next few weeks. The alleged ‘conspiracy’, either real or imagined, might not have materialized at all.