You probably know something about the Civil War draft riots that kept New York paralyzed during the week of July 13, 1863. But New York only meant Manhattan back then. What about the rest of the future boroughs?

The conscription act initiated draft lotteries throughout the area as, by 1863, the Union struggled to fill its quota of volunteers. Many thought the state of New York had contributed enough; hundreds were already dead after two years of bleak and depressing battle.

Then there was that troublesome little exemption clause. Those chosen in the ‘wheel of misfortune’ could either find a substitute or pay a $300 commutation fee. According to the Inflation Calculator, that’s about $5,250.00 today. Look at your bank account. Could you afford to pay that?

People revolted violently when the drafts were held in New York on July 13. There were also seismic reactions in the surrounding counties as well, chain reactions of the anger quelling in New York. In the surrounding regions, local law enforcement were often better prepared to handle disruptions amongst their less concentrated populations. Even still, the horror of New York’s draft riots did spread.

The homes of many black residents on Staten Island were torched. According to historian Richard Bayles, “From its proximity to New York City this county could not help but feel every pulsation of popular emotion that disturbed the bosom of the city.” Mobs attacked black shopowners in Factoryville, surrounded a black church in Stapleton and threatened parishioners inside, and burned down a railroad station owned by Republican and Union supporter Cornelius Vanderbilt.

Residents from the village of Astoria and the farmlands of Sunnyside and Ravenswood could see New York burning across the water. But Queens County caught the loathsome riot fever when the draft commenced in nearby Jamaica, on July 14. Riled crowds gathered at dusk and nearly torched the village but for the intervention of a few Democratic community leaders.

The draft office in Jamaica was eventually destroyed and number of buildings filled with government property were vandalized. Rioters stormed one building and stole piles of garments intended for the battlefield. According to an 1882 history of Queens County, it was an apparel Armageddon, the rioters “taking out some boxes of clothing which they broke open, piled in heaps and set on fire. The largest pile, which they derisively called ‘Mount Vesuvius’ was about ten feet high.”

In Westchester County, towns along the Bronx River reacted similarly to their own draft lotteries, with rioters in Morrisania and West Farms destroying telegraph offices and yanking railroad ties from the ground. However, other local towns, like Yonkers, were successfully insulated from violence, due to better living conditions and the entreaties of an especially popular local leader, the Rev. Edward Lynch. A mass gathering on July 15th in the village of Tremont eventually snuffed out violence in the region.

Although it was one of the country’s largest metropolises, the independent city of Brooklyn never saw the intensity of violence that New York did. Indeed, some black New Yorkers escaping violence in the city fled to the countryside in Kings County, to places like Weeksville. However the county did see a good share of bloodshed and destruction, particularly in the Eastern District (the areas of Williamsburg and Greenpoint).

The Brooklyn Eagle, solidly Democratic and in quiet support of the anti-draft agitators, had this to say in a July 16th article, “We could fill columns of the Eagle with exciting stories of anti-negro demonstrations, threatened outbreaks, etc.. So far no disturbance has occurred in Brooklyn which two or three policemen could not surprise [sic]. There has been nothing like any attempt to get up a mob, or create a riot.”

This is preposterous, but even through the Eagle’s glossy lens, it’s apparent that violence never fomented to the degree that it did in New York. This, of course, would be of cold comfort to the dozens of black Brooklynites who did have to flee their homes and businesses that week.

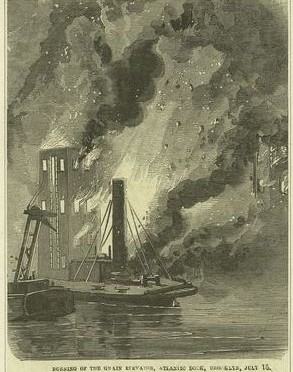

The most dramatic scene in Brooklyn took place before midnight on Wednesday, July 13, with the destruction of two large grain elevators in the Atlantic Basin, in Red Hook. (Pictured at top.)

The Eagle’s reasoning for the blaze demonstrates the reasonless chaos that typified violence in the latter days of the riots. It had nothing to do with racism or with drafts, but rather “[t]he fire was the work of incendiaries, supposed to be grain shovellers who recently had some trouble about a raise on wages, and who have always looked with feelings of animosity on these elevators because they dispensed with a large amount of manual labor.”

The burning elevators, facing into the East River, made a grim bookend to the burning structures across the water in New York. Luckily, within 24 hours, the riots would be calmed throughout the region.