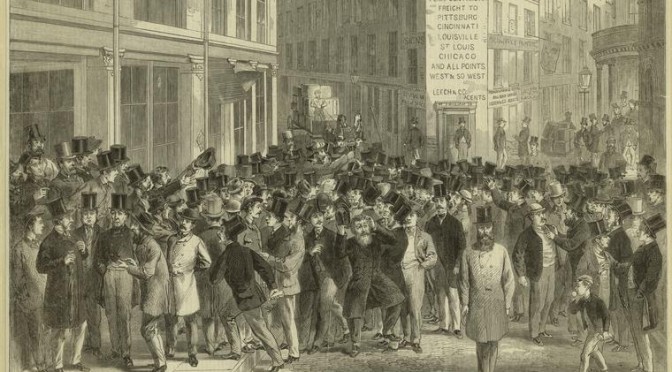

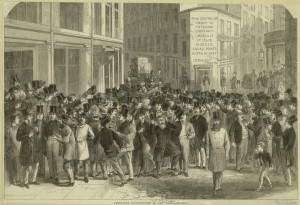

Wall Street’s curbside traders, in the throes of unregulated buying and selling.

From here until next Friday and the release of the next podcast, I’ll be posting stories from a particular, namely the year 1864. It’s one of the weirder years in New York City history.

You would think that having part of your city in ruins due to the Draft Riots in 1863 might demoralize a city. You might think four years of war, overcrowded slums, burgeoning street violence, and ever sophisticated methods of government corruption (via a newly empowered Tammany Hall) would send the city’s fortunes into a tailspin.

In fact, New York in 1864 proved the adage that war makes for good business. Still seen in some circles as a Southern ally, New York regularly traded with the South. And the city’s merchant class flaunted its wealth with new homes and imported fashion, even while making grand but ultimately shallow gestures to curtail its luxuries.

Wall Street was benefiting grandly, and an innovation in 1864 would change the way stocks would be traded, increasing the number of transactions and paving the way for American Gilded Age wealth.

Before 1864, shares were still be sold in a traditional auction format with comparatively few transactions during only two sessions a day. The previous year, the New York Stock And Exchange Board had changed its name to the New York Stock Exchange and had commissioned a beautiful new home at 10-12 Broad Street. The building would be completed a year later. But some radical traders, impatient with the stodgy board and its traditional method of selling, couldn’t wait for the new trading floor.

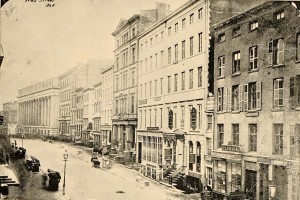

Below: The south side of Wall Street, circa 1864. At the far left of the picture is the Merchants Exchange building at 55 Wall Street. Broad Street and the Long Room would be to the right of the camera.

In 1864, these traders, operating as the Open Board of Stock Brokers, rented out another room at 18 Broad Street. (The current stock exchange building is at this address today.) The room is historically called ‘the Long Room’, although there are many long rooms associated with New York history, such as the long room of Fraunces Tavern and Martling’s Long Room, the birthplace of Tammany Hall.

In this Long Room — “a cockpit 145 feet long and 45 feet wide” [source] — traders broke out of the auction format and began a method of continuous trades, occurring all at once, throughout the day. A circus-like atmosphere prevailed, a claustrophobic display of activity that could be witnessed by curious onlookers from above. The layout presaged the modern trading floor, with various ports where multiple stocks could be traded simultaneously. Traders floated from spot to spot in a constant state of transaction.

Another feature that resembles today’s traditions was the Long Room’s exclusivity. Just as one may purchase a license to physically trade on today’s stock market floor, the Long Room also has annual fee for admittance. Another source says there was a lofty door fee of $50.

This single expansion of business exploded the stock market, increasing business tenfold. According to Jay Gould biographer Edward Renehan, “in the 1860s, the Regular Board might see $7 million in business on any given day, and the Open Board $70 million.”

The ‘regular’ stock exchange was seen as more reputable, but the continuous market — and the even shifter street corner traders (pictured at top) — was clearly making people wealthier. And naturally, this opening of financial floodgates encouraged hysteria and eventually vast malfeasance.

You can argue that America would not have become the nation it did without this accelerated alteration to the stock market, but you cannot argue that this ‘improvement’ made the industry more prone to speculation and outright manipulation.

For more information on the history of the stock exchange, check out our podcast on the New York Stock Exchange, newly ‘illustrated’ and up on our archive feed. Download it from here.

Top pic courtesy NYPL.