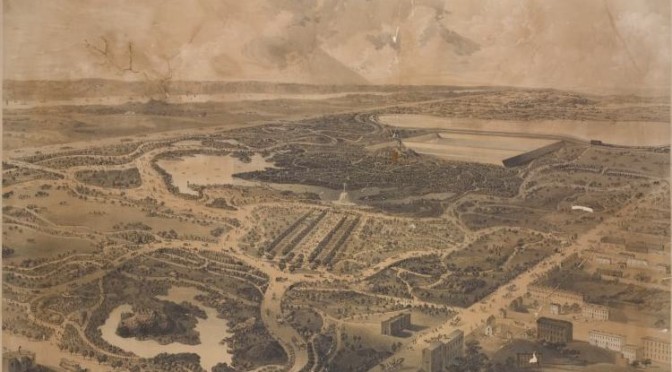

A depiction of Central Park from 1864. The conspirator’s cottage hideout would have been near the southeast corner. (Courtesy NYPL)

The year 1864 wasn’t as pivotal to New York City as 1863 (with the Draft Riots), but it is one of the stranger years I’ve ever come across in studying the city’s history, culminating in the failed attempt by Confederate spies to burn Manhattan’s hotels.

There is one important context about the attempted burning that we failed to mention. You couldn’t just walk around New York City in late fall 1864 if you were a Southerner. Because if intelligence claiming a potential attack on the city, any resident of the South had to register with the city. Our eight Confederate spies, of course, neglected to do this, and although they did indeed wear disguises and shuffle among different hotels to avoid detection, there is no evidence to suggest they disguised their voices.

A few other non-war events from 1864 that were not mentioned in the show:

Central Park was open to visitors but was far from completion. The new public space still felt remote to some New Yorkers — of the human kind, that is. People had begun abandoning unwieldy pets or livestock by securing them in one particular area of the park, in the southeast corner. In 1864, it became an officially chartered menagerie of animals, one of the first official American zoos.

Also that year — and quite against the original designs of Olmsted and Vaux — Central Park received its first statue. The honoree? William Shakespeare.

The area surrounding Gramercy Park was well established by Manhattan’s elite. Years after the disgrace of having a brother by the name of John Wilkes Booth, famed actor Edwin Booth would open his Player’s Club here. But further down on Irving Place, on 18th Street, a modest grog shop opened in 1864 on the ground floor of a building called the Portman Hotel. Drinkers there were certainly gossiping about the war and the Confederate attack on New York. The tavern has survived through various name changes and more than a few drunken artists and writers (including, most notably, O. Henry). You may know better today as Pete’s Tavern.

Some young men spend 1864 holding baseball bats, not rifles. The Brooklyn Atlantics were certainly one of the most well-known ball teams of the mid-19th century and one of the founding members of America’s first baseball league. And in 1864, the team played an undefeated season to capture national championship. (To be fair, to the team they bested was Eckford, also a Brooklyn team.)

For More Information: For a nice overview of New York City during the Civil War, seek out the out-of-print The Civil War and New York City by Ernest A. McKay. Nat Brandt’s The Man Who Tried To Burn New York takes a closer look at Robert Cobb Kennedy, one of the Evacuation Day conspirators. For a look at the conspiracy from the larger context of the war, check out Clint Johnson’s A Vast And Fiendish Plot. And of course, the excellent website Abraham Lincoln and New York, presented by the Lincoln Institute, is worth a look.

The Show Must Go On: And finally, in full, here is P.T. Barnum’s letter to the New York Times regarding the attempt by Robert Cobb Kennedy to burn down his American Museum.

“To the Editor of the New York Times:

In view of the announcement in the morning papers of the attempt to fire my Museum last night, as well as other public buildings, I wish to state the following facts:

Everyday from sunrise until ten o’clock P.M., I have eleven persons continually on the different floors of the Museum, looking to the comfort of visitors, and ready at a moment’s warning to extinguish any fire that might appear. From 10 o’clock at night until sunrise, I have from six to twelve persons in the Museum engaged as watchmen, sweepers, painters, &c.

I always have a large number of buckets filled with water on and under the stage, and a large firehose always screwed on to be used at a second’s notice. I never allow an uncovered light in the Museum, and I heat by steam from a furnace in the cellar.

As a proof of the efficiency against fire, I submit the fact that instead of “slight damage” being done to the Museum last night, as reported by a morning paper, so speedy was the extinguishment of the flames arising from the liquid ignited on the stairs, that not even a scorch is visible.

My own sense of security is proved by the fact that I never insure for one-third the value of the Museum property.

For the safety of visitors in the lecture-room, I long ago opened nine different places of egress, so that the lecture-room, if filled with visitors, could be emptied in from three to five minutes, and the spacious openings to the street in Broadway and Ann street, render mine, I think, as safe a place of amusement as can be found in the world. The Fire Marshal and insurance agents will corroborate this statement.

Very Respectfully,

P. T. BARNUM

AMERICAN MUSEUM, Nov. 26, 1864″

2 replies on “Notes from the podcast (#128): The Conspiracy of 1864”

I wondered about the disguises. Weren’t they more likely to be considered suspicious with their fake moustaches than to be recognized as Confederate spies?

My impression is that only some wore disguises, and for only part of the time. The conspirators each changed hotels a few days at a time. Since they were in the city longer than anticipated, some may have thought that might have been suspicious and changed their appearance. Also they were young and unexperienced.

On the day of the fires, many of them were quite conspicious because of their appearances or actions. I would have thought something else would have given them away more quickly — their accents. But truth be told, there were many Southerners in the city.