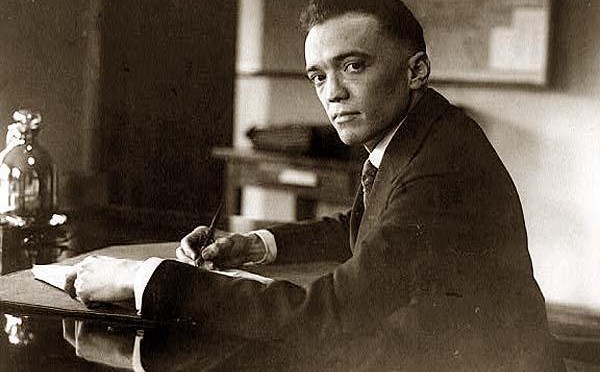

Work hard, play hard: The FBI director in his early days

There are at least three scenes in the new Clint Eastwood-directed J. Edgar Hoover biopic ‘J. Edgar’ set in New York, one of which might surprise you.

The first features Hoover on Ellis Island, but he’s hardly there to greet new arrivals. The FBI director’s early career was spent ferreting out and deporting anarchists, and his biggest target was Emma Goldman. On October 27, 1919, Goldman was put on trial at Ellis — in the film, the Statue of Liberty stands at odds in the background — and she was eventually expelled from the United Statues using a tenuous interpretation of the status of her American citizenship.

The second scene, depicting the rural Bronx of 1933, typified Hoover’s career in the 1930s as a stiffly facaded embodiment of law enforcement. Here the movie envisions the arrest of Bruno Hauptmann, accused kidnapper of the child of Charles Lindburgh. Hoover’s interest in the case represented an expansion of federal powers for the agency, even if Hoover’s actual involvement is questionable.

But it’s the third view of old New York that I found more intriguing. Hoover was a teetotaler early in life and demanded his agents aspire to clean, moral living. So its interesting that he — and his companion Clyde Tolson — were regular habitues at New York’s hottest nightclub of the 1930s — the Stork Club.

Sherman Billingsley, a former bootlegger, would have been made Hoover’s enemy list during Prohibition. Instead, he regularly hosted the FBI director as his swanky club at 3 East 53rd Street (at Fifth Avenue).

Hoover schmoozed here with people who were useful to him, journalists like Walter Winchell who assisted with the capture of most-wanted criminals from his banquette in the Cub Room. The unscrupulous columnist was instrumental in the surrender of Louis “Lepke” Buchalter, leader of the mob’s assassination unit Murder Inc., and helped play up the image of Hoover’s G-Men to his millions of readers. In return, Hoover sometimes provided Winchell with FBI employees as bodyguards or drivers.

Winchell and others considered the Stork Club an invaluable nexus of social connections, and Hoover too made it his hangout when he was in town, often downing champagne and chatting with glitterati. The director was so associated with the nightclub in the 1930s, Tolson at his side, that adversaries sometimes called him ‘the Stork Club detective’.

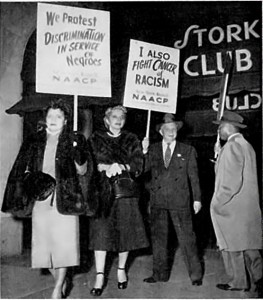

In a telling incident a few years later, in 1951, iconic entertainer Josephine Baker was denied service at the Stork Club. She filed a complaint with the police department, and supporters organized a protest outside the nightclub (pictured at right). When it was recommended that Hoover intervene on the behalf of Baker, he replied, “I don’t consider this to be any of my business.” [source]

Here’s a collection of photos of the Stork Club with musical accompaniment. Mr. Hoover appears in one image around minute 2:40:

Stork Club logo courtesy Daddy O’s Martini blog