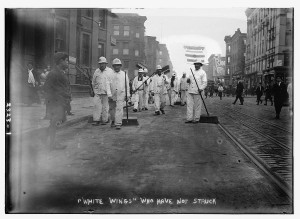

Above: a typical scene during the Garbage Strike of 1911

New York street cleaners and garbage workers (sometimes referred to as ‘ashcart men’) went on strike on November 8, 1911, over 2,000 men walking off their jobs in protest over staffing and work conditions.

More importantly, that April, the city relegated garbage pickup to nighttime shifts only, and cleaners often worked solo. This may have been acceptable in warmer weather, but winter was approaching. At a union rally that evening, a union representative proclaimed, “A 200-pound can was a mighty big load for one man to lift into a garbage wagon ……. [Our] men are already falling ill with pneumonia and rheumatism and … they demanded the right to work in the sunlight and the warmer weather of the daytime.”

By Nov. 11, garbage was heaped along street corners, and coal ash swirled into the street, creating a blackened, smelly stew in the streets. The city brought in temporary workers to carry off the more egregious piles of filth away, but harangues and violence by union protesters required they be protected by police.

New Yorkers had lived through such a strike before, as recently as 1907, but strikers found little public support this time around. Newspapers, little sympathetic to the strikers, highlighted the growing threat of disease and the perceived selfishness of the workers. “The right to strike of public employees, who enjoy the advantage of being listed in the civil service, is more than doubtful,” said the New York Times.

During bouts between strikebreakers and police, over two dozen people were injured and one man was even killed by a falling chimney. Meanwhile, Mayor William Jay Gaynor was resolute in rejecting the cleaners demands. The efforts of the workers failed, and many went back to their jobs the next week, some heavily penalized for their participation in the strike.

Below: the city shipped in workers from out of town to sweep the streets during the strike