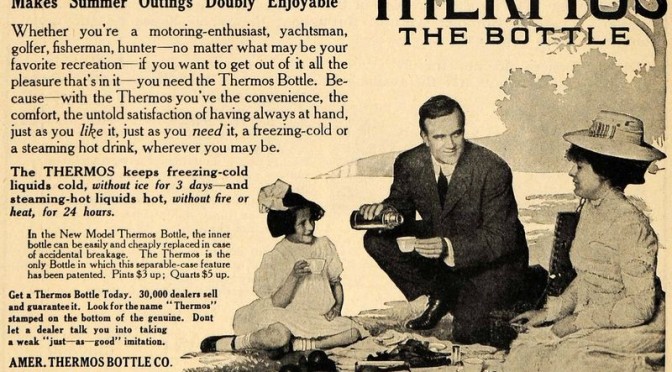

A charming family enjoys its insulated beverages — just as they like it, just as they need it — in an ad from 1909.

The invention of the vacuum flask in 1892 (by Scottish chemist Sir James Dewar) does not rank high among mankind’s most remarkable inventions, but its longevity relies on being a steady companion. The first gas-operated motor vehicle debuted in Massachusetts the following year. In an era before disposable containers, the vacuum flask came along at exactly the right time. Now, people could travel long distances of their own accord and drink a hot beverage along the way. In the 1890s, the road trip was born.

Believe it or not, Dewar was not a member of the family that produced the famed Scottish whiskey, although I suspect much of that intoxicant has been stored in Dewar’s vacuum invention. Like many inventors, Dewar was not terribly business-savvy, and he failed to properly patent and profit from his own creation, unsuccessfully taking rivals to court.

One of those competitors, the German glass blowers Burger and Aschenbrenner, ran away with the industry. They loosely named their revised vacuum flask after the Greek word for ‘heat’ and began producing the Thermos for local use in 1904. Two years later, William B. Walker, an American visiting the Munich-based Thermos plant, became enamored of the magic container and obtained a license from the Thermos company to bring the product to America the following year.

Walker opened the American Thermos Bottle Company in 1907, producing the containers out of a small factory in Brooklyn, in the shadow of the Manhattan Bridge. (Today’s DUMBO neighborhood, 31 Washington Street, to be precise. The building is all condos today, so that means one or more people are living in an old Thermos factory as you read this.)

His timing could not have been more divine. Auto dealerships began popping up around Times Square, driving a market for accessories. New York’s continuing construction boom — paired with less advantageous lunch-break privileges — suggested new uses for the Thermos.

But most likely it was Walker’s clever marketing strategies that made the Thermos a desirable product. As seen in the advertisement at top, the Thermos brought the family together. It was traditional. At the same time, it was a marvel of invention, at an affordable price. An ad (at right) that ran 100 years ago today, in the New York Tribune, heralds its appropriateness as a Christmas present. “It does just what everyone wants done — it keeps coffee, tea, soup, etc., hot for 24 hours.”

Walker soon expanded the Thermos company. While his marketing and distribution team moved to a swank office near Madison Square (1171 Broadway), his production facilities moved to Chelsea in 1910, to 232 West 18th Street, with additional entrances on West 17th Street. “The building will hereafter be known as the Thermos Building,” proclaimed the New York Times.

The product began popping up in truly odd places, all engineered for the maximum of publicity. Most of the 200,000 New Yorkers who lined Broadway for an “automobile carnival parade” in 1909 observed one prize-winning vehicle — a car in the shape of a Thermos bottle. (The Thermos car below is from the 1909 Vanderbilt Cup races, in Long Island. I imagine it must be the same vehicle. Pic courtesy Vanderbilt Cup Races.)

The Thermos made a stout companion during the era of exploration. E. H. Shackleton had one during his 1909 voyage to the South Pole, as did Robert Peary on a his similar expedition north. The Wright Brothers allegedly had one on their early planes. Back on Earth, so did the President of the United States that year, William Howard Taft.

Christmas shoppers along Ladies Mile, not far from the Thermos Building, would have found a wide selection of sizes. According to Charles Panati, “A quart-size Thermos sold for $7.50; the pint size for $5.00.” Those are appliance prices; according to the Inflation Calculator, a $5 Thermos in 1910 is equal to a $115 product today. (I don’t know what that ad above is talking about with its $1.00 Thermos.)

Demand soon required larger facilities, and the Thermos company moved out of the Thermos Building. But not before a disaster that struck on May 1, 1913, a fire that quickly swept through the structure, rather unsettling in light of the Triangle Factory Fire that occurred just two years before. Luckily, most of the Thermos employees were out to lunch, and a hero, “Samuel Gumps, a negro elevator man” rescued employees from the top floors. Although “several girl employees” were forced to escape to the rooftop.

The Thermos company moved its headquarters to Norwich, Connecticut. Today the building is a basic residential address, its Thermos Building name long forgotten. (As the building cuts through the block, it’s known today as 245 West 17th Street.) On the 18th Street side, it’s just next door to Barney’s Co-Op. Perhaps they sell Thermos there?

By the way, I love that in the early days of this product, it was sometimes marketed as ‘Thermos, the Bottle.”

1 reply on “The Thermos Building, keeping it hot (and cool) in Chelsea”

[…] blog post on the website The Bowery Boys: New York City History, (“The Thermos Building, Keeping it Hot and Cold“) describes some of the ingenious marketing that Walker employed to make Thermos the huge hit […]