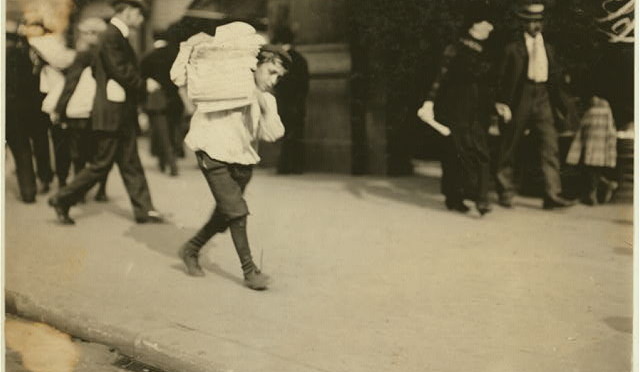

The grueling life of a Brooklyn newsboy, taken by Lewis Hine, 1910 (Library of Congress)

The new Disney-produced Broadway musical ‘Newsies‘ puts melody to the events surrounding the Newsboys Strike of 1899. For one week that summer, young newspaper sellers fought back against their employers’ unfair pricing schemes, turning their former street corners into places of mass protest. [You can hear all about in our 2010 podcast on The Newsboys Strike of 1899.]

But did the producers of the Broadway show realize they’re opening their new musical on the anniversary of another significant strike?

The organized disobedience of 1899 was only the grandest of New York’s newsboy strikes. Despite their youth and inexperience, newsies fought back on several occasions throughout the late 19th century. While the image of the street-smart, scrappy whelp was a stereotype often relayed by the newspapers themselves, in some cases, journalism’s youngest workforce used its hot-blooded pluck to great advantage.

With the growth of New York after the 1850s came a fierce competition among its many dozens of newspapers, leading to lamentable and unfair business practices aimed at those who actually sold their product. After all, selling newspapers was a grueling job with low financial reward. Adults looked elsewhere for higher paying work, so in the era before substantial child labor laws, newspapers often employed younger New Yorkers, mostly boys. And children, cynical publishers believed, were a pliable workforce.

The independence the job required initially appeared to discourage any kind of organization, and newspapers felt they could systematically underpay their ‘freelance’ sellers, often pitting groups of newsboys against each other. A newspaper across the East River, in the pre-consolidation city of Brooklyn, made just such a mistake in March of 1886.

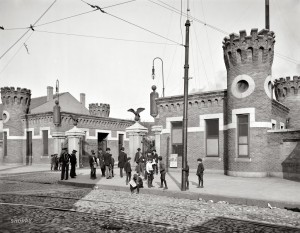

Above: Determined Brooklyn newsies hang around the Brooklyn Navy Yard (at Sands Street) looking for potential buyers. 1903 Picture courtesy Shorpy

Brooklyn Takes Sides

The Brooklyn Times employed newsboys all throughout the city of Brooklyn, a fast expanding metropolis by the mid-1800s. Originally just the area we consider Brooklyn Heights and the Fulton Ferry, the burgeoning city grew to absorb many Long Island towns along the bay. In 1854, it also expanded to include the independent city of Williamsburgh (today’s neighborhood drops the -h) and Bushwick. These new additions were often referred to as the Eastern District.

However, the city of Brooklyn had a good deal more expansion ahead of it and would eventually swell to include many towns south and southeast of its original borders, an area referred to back then as the Western District, including areas like Bay Ridge, Red Hook, and many others. (This is a tad confusing today as many of these areas were later called South Brooklyn; the Eastern/Western distinction makes sense of you orient it with ‘true north’.)

In an effort to expand sales into the newer regions of Brooklyn, the Times made a unique deal to Western District newsboys. They would receive stacks of newspapers at a lower cost (one cent per paper) than those sold to Eastern District newsboys (one-and-a-fifth cent per paper). The Times publishers believed this would boost sales by encouraging the Western District newsies to “push sales vigorously in new directions.”

Above: Newsies gathered near the Brooklyn Bridge. Courtesy NYPL

Riot on South Eighth Street!

Oh, but when the Eastern District newsboys found this out the following day! On March 29th, according to a report by the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, a hundred newsboys, armed with sticks and stones, stormed the Times distribution offices at South Eighth Street and tried to prevent two wagons of newspapers from heading to the Western District. A whip-wielding wagon driver and arriving police officers thwarted the boys, but one of the trucks was later overturned at the area around today’s Brooklyn Navy Yard.

Many Williamsburg newsies refused to sell the Times, even defying orders of older, more compliant newsboys. Wagons filled with papers were continually attacked on their way south. Any regular newsboy caught selling the Times was set upon by other boys, often roving bands “backed by a number of roughs.” The Daily Eagle reports of some young newsies hiding newspapers in their jackets, selling them to customers in secret, for fear of reprisal.

The Brooklyn newsboy strike lasted for a couple days. Like the later newsboys strike of 1899, the key to success came from adult newspaper sellers at regular newsstands. Once a few of them joined the boycott, the Times agreed to lower their wholesale cost to just one cent per paper for newsboys in both areas of Brooklyn.

By April 1, 1886, newsies returned to their street corners, their hands stained with the ink of the Times and glowing with the satisfaction that their efforts might reward them with a little extra money that day.

SIDE NOTE: It’s probably a good guess to say that many of these young workers lived at the Brooklyn Newsboys Lodging House at 61 Poplar Street, which opened its doors in 1884, one year before the opening of the Brooklyn Bridge.

3 replies on “Before ‘Newsies’: The Brooklyn Newsboys Strike of 1886”

Thanks for this excellent article just in time for the May 1st General Strike!

http://strikeeverywhere.net/

I’m a new listener and enjoy what you guys do very much. Thanks for everything.

Amazing story