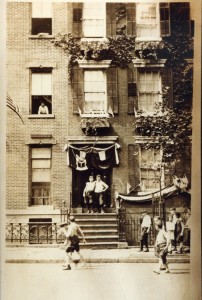

Children gallivant and pose for pictures outside 265 Henry Street, date unknown (Courtesy Henry Street Settlement)

FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION Until May 21st, you can vote every day in the Partners In Preservation initiative, a program that will award grant money to certain New York cultural and historical sites among 40 nominees. Having trouble deciding which site to support? I’ll be featuring a few select sites here on the blog, providing you with a window into their history and hopefully giving you many reasons to visit these places, long after this competition is done. Read about other candidates here.

Historic Site: Henry Street Settlement

Without perhaps intending it, social services pioneer Lillian Wald, in her desire to help thousands of poor immigrant women and children in the Lower East Side, also saved a rare and forgotten part of New York City history.

The modern Henry Street Settlement is spread throughout several buildings in the neighborhood, providing health care, shelter, job training and a host of services to the community. But it started out in just three adjacent Federalist-style townhouses on Henry Street, recruited into duty by Wald and her benefactor Jacob Schiff to stem the tide of disease and harm that threatened families in the world’s most densely populated neighborhood in the late 19th century.

A Different Lower East Side

As New York grew northward in the 19th century, wealthy landowners carved up their land with hopes of profit and a desire to foster New York’s next great elegant neighborhood. Revolutionary War colonel Henry Rutgers, who lends his first name to the street where the Settlement makes its home, sold off his property near Corlear’s Hook to businessmen with financial concerns along the Manhattan waterfront.

Below: An illustration from Forgotten NY, outlining the dividing line (literally, Division Street) between surrounding properties and Rutger’s own (in yellow). The buildings discussed are at Henry and Montgomery.

Many of the great shipbuilders lived in today’s Lower East Side (in the 1810s, it might have been called the Upper East Side) in fabulous residences within walking distance of the shore. Even by the 1850s, when the character of the neighborhood began to change, the mayor of New York Jacob Westervelt still resided at 308 East Broadway close to his shipyards. His neighbor at 281 East Broadway was city surveyor Isaac Ludlam.

Typical of the buildings that defined the neighborhood were 263 and 265 Henry Street, Federalist townhouses built in 1827. Its neighbor 267 Henry Street is a touch more ornate, with a different shade of brick in a Georgian Eclectic style.

Picturing these streets today lined with such buildings is requires a vivid imagination. That’s because of the sudden mass of immigrants who arrived in New York by the 1850s, moving into poorer neighborhoods along the waterfront and in places like Five Points. Most of the homes along once-elegant Henry Street were torn down and replaced with tenements. Later, many of those tenements were themselves replaced with blocks of apartment complexes in the early 20th century.

These three Henry Street buildings have survived (as well as a few others, including Ludlam’s old home) because they were repurposed by a woman of uncommon compassion, one of New York’s most important figures in health and social services.

Settling Down Lillian Wald first came to the city in 1891 as a student of New York Hospital’s nursing program. An intelligent and ambitious woman from Rochester, Wald quickly found purpose in one of the few respectable professions in the late 19th century where women could rapidly excel. She’s marveled at today as a person of extraordinary compassion. But in many ways Lillian was a modern entrepreneur, able to latch onto the progressive instincts of the day to solve the immediate social ills facing New York with great imagination and a bold lack of prejudice.

Lillian Wald first came to the city in 1891 as a student of New York Hospital’s nursing program. An intelligent and ambitious woman from Rochester, Wald quickly found purpose in one of the few respectable professions in the late 19th century where women could rapidly excel. She’s marveled at today as a person of extraordinary compassion. But in many ways Lillian was a modern entrepreneur, able to latch onto the progressive instincts of the day to solve the immediate social ills facing New York with great imagination and a bold lack of prejudice.

When Wald (at right) founded the Nurses Settlement in 1893, she was building upon the practices of altruistic Christian programs (like the Methodist missions into Five Points) that brought social services into the very heart of slum-filled, overcrowded neighborhoods. However Wald was Jewish, and her perspectives involving health care were profoundly nonreligious and ‘universalist’ for the day.

In that year she also met wealthy banker Jacob Schiff (who himself had immigrated to New York in 1865) who purchased the three Henry Street buildings for Wald to properly set up her nursing agency. From that moment, it became the Henry Street Settlement, housing a squad of nurses sent out into the neighborhood to tackle an ungainly number of health issues.

In an era where poor patients were often turned away from standard hospitals, Wald and her team of extraordinary women provided care for free, often risking their own lives to enter squalid tenements and exposing themselves to many illness that today have been completely eradicated. (One of her nurses, Margaret Sanger, would later become America’s leading birth control advocate.)

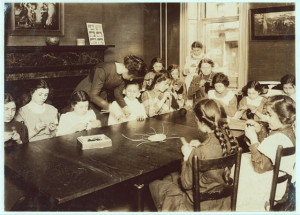

The Settlement had no problem making the former Henry Street residences into working clinics. The rooms still felt like a home in its decor, a respite for many visiting patients. The nurses lived upstairs in rows of small bedrooms, most of which today have been turned into cozy offices. The most lively (and historically important) room at the Settlement was the dining room, with large mahogany tables where Wald entertained a wide variety of guests, from poor patients to the great thinkers and Progressive voices of the day.

Below: A knitting class in the famous Henry Street dining room, May 1910. The fireplace at left is still very much intact. [LOC]

Beyond Borders

The Henry Street Settlement soon expanded its mission statement to generally improve the quality of life in the Lower East Side. Concerned that neighborhood children had no place to play, Wald set aside her courtyard to become one of New York’s first playgrounds in 1902.

Below: The location of the playground, just behind the Henry Street structures.

Wald frequently held meetings here for strikers rallying against the women’s garment industry. In 1909, she invited both white and black guests for a dinner, organizing a group that would soon grow to become the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (the NAACP).

An excerpt from her 1915 book ‘A House On Henry Street‘ illustrates the racial politics of such a seemingly simple dinner party:

“At the time of the first convention of the organization, [the NAACP] formed to further better race relations in this country, the occasion promised to be almost too serious unless some social provision were made.

I suggested a party at the House, but even the organizing committee was fearful. ‘Oh, no!’ they protested. ‘It won’t do! As soon as white and colored people sit down and eat together there begin to be newspaper stories about social equality.’

‘But two hundred members of the conference couldn’t sit down,’ I submitted. ‘Our house is too small. Everybody would have to stand up for supper.’ ‘Then it would be all right,’ they said with relief, and the party was successful.”

Above: One of the two original dining tables. Wald hosted hosted dozens of intellectual luminaries in this room, including Jane Addams, Eleanor Roosevelt, Jacob Riis and Theodore Roosevelt.

Wald would become a leading figure for New York social programs, often enlisted by the city to bring improvement to the city’s other public services. (In 1902, Henry Street’s Lina Rogers become the very first school nurse.) The Settlement even become an important venue for the arts with the debut of the Neighborhood Playhouse theater in 1915. The tradition lives on at the Abrons Arts Center, another part of the Settlement that continues to be a critical part of the Lower East Side cultural community. (At right: A flyer for a WPA meeting, between 1936-41, LOC)

Wald died in 1940, but her Henry Street Settlement has only expanded in the years since her passing. Today they have facilities in over a dozen buildings throughout the neighborhood, expanding their focus to include job training, mental health services, adult education, a shelter for victims of domestic violence and even a computer lab.

Wald died in 1940, but her Henry Street Settlement has only expanded in the years since her passing. Today they have facilities in over a dozen buildings throughout the neighborhood, expanding their focus to include job training, mental health services, adult education, a shelter for victims of domestic violence and even a computer lab.

Those original three buildings, housing mostly administrative offices today, are still a wonderful expression of an early era of New York history. Traces of that history sits next to the practicalities of office life; in one room, an original kitchen hearth and brick oven from the original tenants sit next to a couple photocopiers. Employees sit at laptops in Lillian Wald’s original bedroom with its spectacular sleeping porch overlooking the former playground.

The Henry Street Settlement hopes to use the Partners In Preservation grant money to combat the challenges of keeping their nearly two-centuries old offices in working order, to upgrade and prepare these old rooms for many more decades of providing a little more life to the Lower East Side.

Disclosure: I have partnered up with Partners in Preservation as a blog ambassador to help spread the word and raise awareness of select historical sites throughout the tri-state area. Though I am compensated for my time, I have not been instructed to express any particular point of view. All opinions expressed here are strictly my own. And since writing about New York landmarks is kinda my thing anyway, I’m thrilled to share my love of these places!

2 replies on “Henry Street Settlement: From the doors of old townhouses springs the compassionate heart of the Lower East Side”

Thanks for this lovely post about the Henry Street Settlement. I admire their work but didn’t know much about their history. I love how you present New York City history as relevant to our present moment. Keep up the great work!

It’s so lucky for me to find your blog! So shocking and great! Just one suggestion: It will be better and easier to follow if your blog can offer subscription service.