Mayor Michael Bloomberg‘s latest crusade against sugary beverages in excessively large containers had me thinking about the origins of soft drinks. Most major brands of soda started in the South — Coca-Cola in Georgia, Pepsi in North Carolina, Dr. Pepper in Texas, Mountain Dew in Tennessee. Even the Big Gulp, an invention of the 7-11 convenience stores, originated in Texas. But those companies simply branded and perfected a kind of beverage made popular by the 19th century American soda fountain.

And for the roots of that bubbly innovation, we need to turn our attention — believe it or not — to the Manhattan neighborhood of Kips Bay.

Soda water, an English invention infusing regular drinking water with carbon dioxide, was considered a medicinal treatment during the 18th century. However bubbly water (or “charged water”) would eventually prove to have a variety of tasty uses — as a mixer for alcohol or ice cream, or even as a refreshing beverage itself, if mixed with wine, herbs or spices.

The first attempt to sell New Yorkers soda water came in 1809 when Yale professor Benjamin Silliman installed rudimentary fountains at two prominent locations — the Tontine Coffee House and the posh City Hotel (which opened in 1794). Both places attracted wealthy businessmen, and Silliman attempted to sell his carbonated mineral water, generated from a manual pump, as a wine mixer and as a healthy elixir on its own. Technical problems bedeviled Silliman — the pumps produced irregular carbonation — and he even ran up against false reports of the deadliness of chilled beverages. “Swallowing a large ice cube was thought to cause spasms of the stomach and fatal inflammation of the bowels.” [Darcy O’Neil, source]

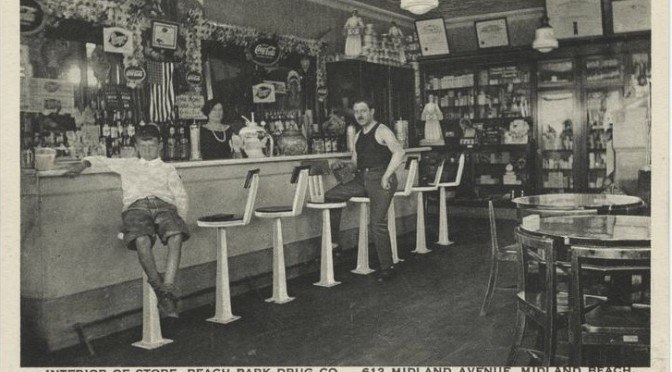

As a light beverage, soda water still had a way to go. But early American pharmacists were attracted to the supposed tranquil qualities of warm soda and slowly began installing fountains in their shops. Later, even when its curative properties were largely disproven, pharmacies continued to install soda fountains as a way to attract customers.

As a light beverage, soda water still had a way to go. But early American pharmacists were attracted to the supposed tranquil qualities of warm soda and slowly began installing fountains in their shops. Later, even when its curative properties were largely disproven, pharmacies continued to install soda fountains as a way to attract customers.

At right: A selection of soda fountains displayed at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition in 1876

In the mid 19th century, these early soda fountains were principally manufactured by two businessmen — John Lippencott in Philadelphia and John Matthews in New York. They would design rival soda fountain machines that would define the industry.

Although Lippencott trumped Matthews by first debuting machines that directly dispensed varied flavors, his New York rival eventually made the bigger splash.

Matthews was an English immigrant and former apprentice to lock maker Joseph Bramah, the inventor of the hydraulic press and an early developer of the indoor toilet. The young apprentice moved to New York in 1832 and set up his own modified water carbonation pump in a shop at 55 Gold Street.

The key to Matthews success was sophisticated equipment and one rather unappetizing-sounding addition — the use of ground-up marble chips to produce the carbonic acid gas for his water. Matthews procured these bits of marble from architects around the city and later even scooped up several barrels of the stuff from the construction site of St. Patrick’s Cathedral!

Matthews’ most famous employee was likely Ben Austin, a Southern freed slave who operated one of Matthew’s portable pushcart fountains and was known for testing the pump pressure by holding his thumb upon the instruments. “If this thumb was forced away by the pressure the fountain was charged,” wrote the New York Times, who recounted the story of ‘Ole Ben’ as though it were a folk tale.

John Matthews was a savvy operator, hiring inventors to streamline his equipment, then purchasing the rights to those inventions outright to mass manufacture. By the 1860s, he had moved production to a plant at 331-337 East 26th Street (at First Avenue) in old Kips Bay, employing over a hundred men to assemble the latest in soda-fountain technology.

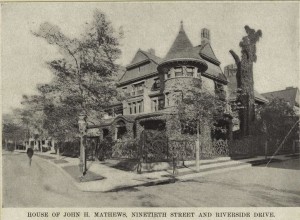

Below: The house that soda built — Matthews mansion on 90th Street and Riverside Drive (Picture spells his name wrong)

With improved technology came better flavors, more consistent carbonation and safer operation. (Early soda-water pumps tended to explode.) And of course greater distribution; fountains were installed not only in pharmacies, but in “hotels, saloons, restaurants” and even street corners. To offer energy and refreshment, some flavored soda waters were infused with exotic ‘healthy’ ingredients, including caffeine or cocaine.

By the time of his death in 1870, Matthews had become the face of soda fountains in the United States, the ‘soda fountain king’ and ‘the Neptune of his trade’, owning hundreds of soda fountains throughout the country. So associated was he with his product that he was interred in a fanciful and commanding tomb in Green-Wood Cemetery, abstractly resembling an old soda fountain and complete with gargoyles that — during rainstorms — dispense a steady flow of water.

His family stayed in the soda game, selling more than 20,000 fountains from this First Avenue factory the following decade. By the end of the century, descendants of the former rivals Lippencott and Matthews would merge with two other companies — like so many industries of this period — to form a virtual monopoly on the soda fountain business.

However, the future of soda would depend on its portability. The drink was still associated with medicinal qualities and people wanted to bring it home with them. Entrepreneurs elsewhere would refine soda for the purposes of bottling and selling for home consumption. While the soda fountain would thrive well into the mid-20th century, its destiny lay in glass bottles. Or, in Bloomberg’s case, large, 16-ounce containers.

Pictures courtesy NYPL, except for the Philadelphia photo, courtesy the Library of Congress

3 replies on “Soda City: NYC’s role in creating Bloomberg’s favorite drink”

Love this story! Thanks.

Great article, but you missed one important person.

Who was Dr. Brown?

I recently came across some books that look to be from John Matthews Personal library with his signature in them. They have the address of his house in New York and some chicken scratch here and there. Very interesting and one of the few articles I have found about how smart this guy was. Not sure what significance the books have, but pretty cool to go down the rabbit hole and find out how important this guy was.