Many of you may remember New York’s sole Republican National Convention, held in 2004 at Madison Square Garden, celebrating the re-election bid of George W. Bush. Some may recall any one of New York’s three recent Democratic National Conventions — two (1976, 1980) for Jimmy Carter, and a rather memorable one in 1992 that placed Bill Clinton on the ticket.

Oh, but that’s modern politics! Conventions of the past — stodgy, contentious, male — are more fascinating artifacts, gentlemanly in tone, chaotic and raw in execution, and dominated by a mix of issues both eternal (war, debt, taxes) and outdated (slavery, territorial expansion).

Of New York’s five Democratic nominating conventions, the most infamous is certainly the 1924 gathering at Madison Square Garden — the old Garden, Stanford White’s palace on 26th Street — distinguished by rancor, the significant influence of an energized Ku Klux Klan and an exhaustive trek through 103 ballots only to settle upon a weak compromise candidate, West Virginian politician John W. Davis, who was crushed in the general election by Republican Calvin Coolidge. Within two years, the Garden would be closed and promptly demolished, as though in embarrassment.

But I find the first national convention, held in 1868, to be the most intriguing and telling of New York life in the mid-19th century, a convention so unusual that the eventual presidential nominee actually recoiled from accepting the nomination.

Four years prior, in 1864, a splintered Democratic Party had tried to replace Abraham Lincoln in the White House with his former Union general George B. McClellan. In New York, former mayor and now-Congressman Fernando Wood led a drive for new national leadership — even though he loathed McClellan — and called for an end to the Civil War with their ‘Southern brethren’. But opposition quickly withered after a series of Union victories, and Lincoln was re-elected.

Flash forward to 1868. Lincoln was dead, the Civil War was over and slavery was abolished. The current president Andrew Johnson aligned with Democrats over Southern inclusion, eventually leading to his impeachment and a serious damaging of the national Democratic brand.

To bring glory back to the White House, the Republicans hoisted forth as their nominee the hero of the war, Ulysses S. Grant. Perhaps the most famous man in America, Grant would eventually prove to be a mediocre president. But his reputation and charm were so great in 1868 that the Democrats knew they stood little chance to defeating him.

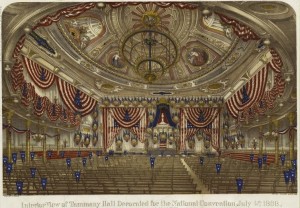

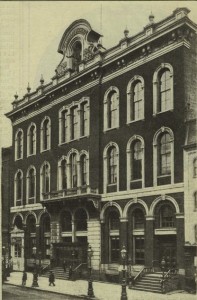

New York’s Democratic contingent — in particular, the political machine Tammany Hall and its leader William ‘Boss’ Tweed — controlled the national committee during this period and steered the convention to New York for the very first time in July 1868.

Their headquarters at 141 14th Street (at left) was sparkling new, ‘fresh from the builder’s hands,’ a lush multi-use venue with auditoriums, clubrooms and even a basement cafe, situated next door to New York’s poshest destination, the Academy of Music.

The convention was especially notable as it featured several Democrats from Southern states for the first time since the war.

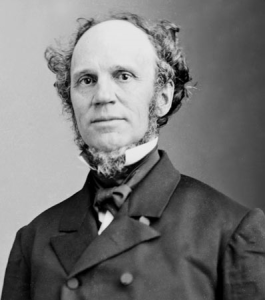

Delegates crowded into the main hall on July 4, and a roar of support greeted Democratic power player (and horse breeder) August Belmont, who gaveled in the proceedings. “I welcome you to this good city of New York,” Belmont declared, “the bulwark of Democracy.” Nearby smiled former New York governor Horatio Seymour (pictured below), president of the convention. Five days later, there were be far less formality and Seymour, in particular, would not be smiling.

On July 5th, the Democrats unfurled their official platform, embracing the return of the Southern states and harshly criticizing the Republican-dominated Congress: “Instead of restoring the Union, it has, so far as in its power, dissolved it, and subjected ten States, in time of profound peace, to military despotism and negro supremacy.” Certainly pleased with this particular inclusion was Tennessee delegate Nathan Bedford Forrest, grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan.

But the Democrats made room for the consideration of progressive causes too, such as a call for women’s suffrage. Seymour read aloud a plank from the Women’s Suffrage Association written by Susan B. Anthony and co-signed by Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

But the Democrats made room for the consideration of progressive causes too, such as a call for women’s suffrage. Seymour read aloud a plank from the Women’s Suffrage Association written by Susan B. Anthony and co-signed by Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

Anthony appealed to their quest for dominance. “It was the Democratic party that fought most valiantly for the removal of the ‘property qualification’ from all white men, and thereby placed the poorest ditch-digger on a political level with the proudest millionaire. And now you have an opportunity to confer a similar boon on the women of the country … a new talisman that will ensure and perpetuate your political power for decades to come.”

The request was greeted warmly by the room before being respectfully dismissed altogether.

Things grew less harmonious when the balloting for president began. Several candidates were submitted, even the disgraced Andrew Johnson. For several arduous ballots, the leader was George H. Pendleton, who had been the vice presidential hopeful under General McClellan. But it immediately became clear that the factions within the party were in no mood to settle quickly.

Pendleton’s lead had weakened by the 13th or 14th ballot, leaving two key candidates — Thomas Hendricks, an Indiana politician, and Winfred Scott Hancock, a Union general that seemed an attractive challenger to Grant. But neither could approach the two-thirds needed to snatch the nomination.

A stalemate called for a third candidate, somebody that all could agree with, while at the same time, an individual that was absolutely nobody’s top choice. It was at the podium that delegates found their man — Horatio Seymour.

He was horrified. Seymour wanted to retire and had previously rejected calls to run for national office. Privately he must have considered the pitiful chances of running a lengthy campaign against Grant. But delegates greatly respected the former governor, a bastion of cool Democratic leadership who had been an opponent to the federal draft during the war. He had also been partly responsible for the Draft Riots, emptying the city of federal militia days before the draft was to begin that July.

He was horrified. Seymour wanted to retire and had previously rejected calls to run for national office. Privately he must have considered the pitiful chances of running a lengthy campaign against Grant. But delegates greatly respected the former governor, a bastion of cool Democratic leadership who had been an opponent to the federal draft during the war. He had also been partly responsible for the Draft Riots, emptying the city of federal militia days before the draft was to begin that July.

Still, their were few ready options for the Democrats. When a delegate from Ohio suddenly declared “against his inclination, but no longer against his honor” to put forth Seymour as a suitable compromise, the room followed suit. On the 22nd ballot, Seymour was enthusiastically declared the Democratic nominee for president.

The only one not enthusiastic about it was Seymour. “I said to them that I could not be a candidate [and] I meant it.” [source] He left the convention in a huff, only to begrudgingly accept the nomination back at Tammany Hall the following day.

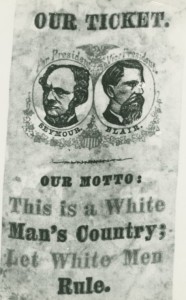

Seymour threw himself into the campaign with vice presidential choice Francis Blair Jr. (whom Seymour barely knew and hardly liked). As evidenced by the campaign poster above, they weren’t afraid to use the Southern racial divide to appeal to voters. But no matter; they lost soundly in the electoral vote to Grant and vice president Schuyler Colfax.

Perhaps the real objective of the convention wasn’t to sway a national crowd, but to energize New Yorkers. Democrats swept into local and state offices, including Boss Tweed’s own choice for governor John T. Hoffman.

Below: Democrats rally in Union Square in support of Seymour and other local candidates, October 5, 1868

Pictures courtesy of New York Public Library

1 reply on “Tammany Hall hosts the city’s first Democratic Convention: Susan B. Anthony, the KKK, and a reluctant nominee”

In my research on my great-grandfather, Soapy Smith I came to the conclusion that politics in the nineteenth century was more important to the average person than it is today. I believe the reason being is that once one side won an election, whether local or national, the losing side could expect to lose their positions and see immediate changes, unlike today’s slow legal process. The elections were also more prone to violence when compared with today’s process.

In 1898 Colorado’s Silver Republicans had two angry factions of the same party vying for the same location to hold their function in Colorado Springs. Rather than debate the issue the men drew guns and shot at one another. One of Soapy Smith’s old friends and Soap Gang member, Joe Palmer, had a rifle bullet score his cheek and “took a piece from the end of his nose.”

Many men of the nineteenth century only befriended their peer party members. It is interesting to note that the combatants in Tombstone’s famed gunfight near the OK Corral, were separated by party affiliation, The Earp’s being Republican’s and the “cow-boy’s” being Democrats. It is no coincidence that the Republican based Epitaph newspaper chose to side with the Earp’s, were as the Democratic based Nugget newspaper favored the “cow-boy’s.”