George Bellows: Retrospective

Metropolitan Museum of Art

November 15, 2012-February 18, 2012

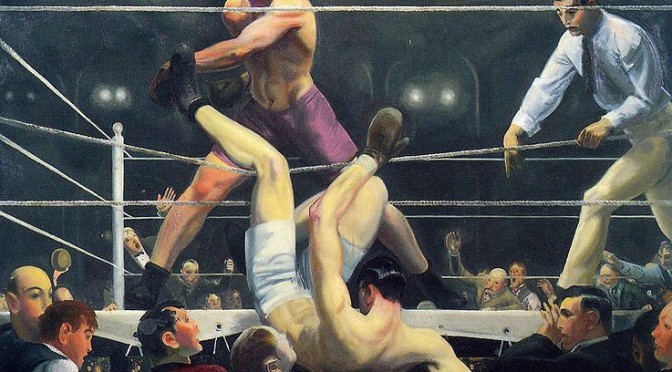

George Bellows was a member of the Ashcan School, the New York-centered realist art movement of the early 20th century. The so-called ‘Apostles of Ugliness’ — at least, according to critics — included John Sloan, Robert Henri and eventually Edward Hopper. Even the photography of Jacob Riis is considered indicative of the bold Ashcan style. Bellow’s painting, in particular, are representative of the movement, using dramatic, almost geometric styling to depict everyday settings that were raw, lurid and sometimes unsettling..

But after a century of photography and film and decades of modern art, Bellows work now seems rather far from real, almost hallucinogenic. A romantic abstraction, the manipulation of light to evoke the senses of the flesh. The imperfections of his subjects, while sometimes ghastly, are flawless ones.

That was my personal impression of the Metropolitan Museum of Art‘s amazing new retrospective of the work of George Bellows, a stunning collection of oil paintings and drawings, most steeped in the rough and tumble of early 20th century New York City.

His subjects include lean boxers in the basement of Sharkey’s Saloon on the Upper East Side, naked East River swimmers, fiery preacher Billy Sunday (Bellows paints Sunday’s upper Manhattan revivals), strolls along Riverside Park, and the excavations of Penn Station. Collected together, you’ll notice many of the images derive their motion from confident broad strokes, slightly distorted and blurred body frames, and a framework that’s almost photographic.

My favorites surprised me with their use of radical light, like his blinding-white winter scene in Battery Park (below) and his stark-green, twisted views of a Newport, R.I., afternoon. The show makes a point of keeping his weirdest work — inspired by not-quite-true stories of World War I atrocities — confined to one room.

Bellows did seek to expose the ruddiness and chaos of urban life, but it wasn’t just for its inherent ugliness that he found it so irresistible. It’s no surprise to find that his home and studio at 146 East 19th Street happens to be on the so-called “Block Beautiful,” Gramercy Park‘s most diversely gorgeous street. There’s even a painting of his elegant home, with his printing press clearly seen on the top floor.

Bellows died prematurely in 1925 at age 42 at the height of his talents, abundantly clear in the exhibition’s final room. It literally feels like an unfinished show, not by fault of the museum, but at the clear superiority of the final paintings.

I still personally think John Sloan is New York City’s greatest painter, but, thank you Met, you’ve almost changed my mind.

By the way, there’s another new show with a connection to New York City history you should check out while here — African Art, New York, and the Avant Garde.