The Williamsburg waterfront was a wall of industry over one hundred years ago and of a most combustible kind.

Manhattan had waterfront industry as well, but it was leveraged with rising skyscrapers. For instance, from the Williamsburg Bridge — not a decade old in 1912 — one could see the nearly-completed Woolworth Building emerging from the downtown skyline. When one turned to the Brooklyn side, however, you were greeted only with towers of belching smokestacks from warehouses and factories, dark, sooty and noxious.

Immediately north of the bridge was the Domino sugar plant, a remnant of William Havemeyer’s century-old sugar concern. Nearby were the oil tanks and plants of Standard Oil, coal yards, concrete warehouses, gas reservoirs and even a marine freight terminal, with storage warehouses with grain and hay. Many workers of these factories actually lived close by in tenements along Kent Avenue.

And right in the middle of all that was the United Sulphur Company*, at Kent Avenue and North 10th Street. On the afternoon of November 25, 1912, an explosion here at the sulphur plant threatened to destroy the entire waterfront.

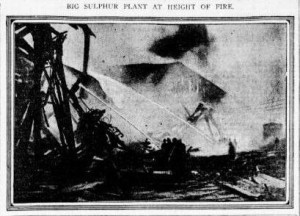

At right: Headline from the New York Tribune, November 26, 1912

Imagine both the sights and the smells of an exploding sulphur factory. Over 5,000 tons of crude sulphur were ignited, created a blast so powerful that some employees were literally blown into the river. Others were trapped in “suffocating fumes” and collapsed.

Newspaper reports made note of various acts of “unselfish heroism” as trained employees “plunge[d] into the yellow glare, shot with blue sulphur flame” to rescue unconscious co-workers.

Two more explosions spread the fire over three blocks, showering fiery embers into the hay bales over at the Brooklyn Eastern District Terminal building and endangering the nearby oil and gas tanks.

Fire alarms rang throughout the entire city, as firefighters from other boroughs soon arrived to help combat the blaze. This was the second time in history that a ‘borough call‘ — essentially, all hands on deck — had ever been made since the consolidation of New York in 1898.

The first would have been fresh on the minds of firefighters rushing to the scene — the devastating blaze at the Equitable Building (in Manhattan, at 120 Broadway) which had killed six people that January. It appears the borough call was not yet in place or was simply not called in 1911, when the fire at the Triangle Factory Fire killed 146 workers.

“This was the hardest fire of its sort I ever experienced,” said New York fire chief John Kenlon of the blaze. Taking seven hours to fully extinguish, the inferno was made worse by the billowing sulfurous fumes which knocked out more than a few firemen and at least four fire horses.

One benefit of the burning sulphur: it smelled so rancid that residents of tenements in the surrounding neighborhood fled early from the smell. A good thing, as the flames eventually destroyed a tenement on Berry Street. A local saloon also caught fire from wisps of burning hay.

Below: An almost abstract photo of the fire from the Tribune.

Hundreds of spectators watched the blaze from the vantage of the Williamsburg Bridge, the sulphur created a thick curtain of smoke; the New York Times claimed that “the flames showed like dancing green sprites through the fog of gas and smoke.”

Unbelievably, despite dire headlines — ‘DEAD IN RUINS OF BROOKLYN FIRE‘ — it appears there were no deaths due to the blaze, but dozens of injuries. It was a true test of the consolidated New York Fire Department, and one they ably passed.

*’Sulfur’ is the more preferred spelling today, but as the original company used the British spelling ‘sulphur’, I have continued that spelling throughout the article for consistency.

Top illustration courtesy New York Public Library