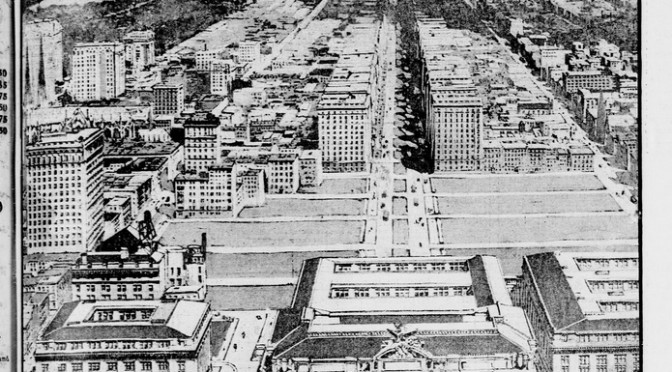

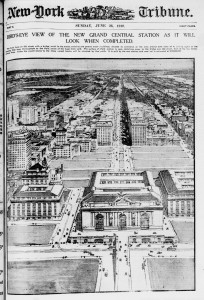

Continuing the celebration of Grand Central Terminal’s 100th anniversary, here’s a look at the proposed street plan which was run in the New York Tribune on June 26, 1910.

“The front faces on 42nd Street, with a bridge crossing that busy thoroughfare to the Park Avenue slope. Under the vacant blocks to the north lie the tracks, switches and mechanisms of the huge train yard. The surface of these vacant blocks will be occupied by fine buildings, devoted to commerce or to the arts.

Park Avenue is seen stretching away to the north. It is split by a new station and runs around both sides of it, joining again at the bridge over 42nd Street. Cost of this new terminal is estimated at $180,000,000.”

This was the beginning of the ‘Terminal City’ plan, a group of linking buildings with similar design. Sadly, many of those buildings were never built, and those that were have been torn down during the furor of the midtown skyscraper boom.

The plan below shows Terminal City from a different angle, and with new features:

The uniformity intended for Terminal City stands in stark contrast to the multiplicity of towering structures in the area today. In particular, the graceful New York Central Building (today the Helmsley Building) would finally rise to Grand Central’s north in 1929. The decidedly ungraceful Pan Am Building (today the MetLife Building) was planned during the late 1950s, when commuter travel by train decreased and Grand Central was considered an antiquated relic.

But it’s not what you see that New Yorkers marveled at back in 1910. It’s what you didn’t see. “[A]ll of this machinery of this vast terminal — the signals, the tracks and the hundreds of trains — will never be seen from the street,” proclaimed the 1910 Tribune article. “They will be less in evidence than the engines at the heart of an ocean liner.”

Electric trains afforded such a disappearance from street level, creating an entirely new boulevard from 45th Street to 57th Street. In some serious understatement, the Tribune continues, “These changes will revolutionize the character of this part of the city. Along the new part of Park Avenue will be constructed a mile and a half of imposing apartment houses.”

Spectacular apartment complexes would appear on Park Avenue, but mostly above 57th Street. Commerce would eventually fill in the block below, bringing the most innovative skyscrapers of the 1950s, structures like the Seagram Building at 52nd Street and the Lever House at 53rd Street, buildings which toyed with the city’s zoning laws and created new public spaces.

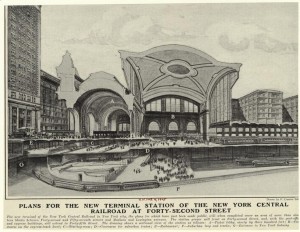

Below: A cross-section plan of the new structure, created in 1905, focuses on what would have focused on the terminal’s most magnificent secret — the buried tracks and public spaces.