Theodore Roosevelt in 1908, in a rare shot with his pince-nez lowered.

Checking the mailbox was a frightening experience for some New Yorkers almost a century ago.

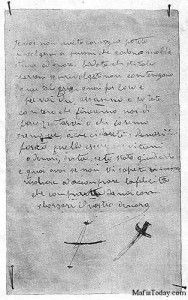

Some found extortion notes — threatening letters, demanding large sums of money or else — courtesy Italian gangsters collectively referred to in the press as The Black Hand. Most of the targeted addresses belonged to newly arrived wealthy Italian immigrants, often celebrities or successful business owners. Famed tenor Enrico Caruso was even a victim of the Black Hand’s extortion in 1920. “I laugh, ho ho, to show me myself that I fear not,” the singer claimed, although he ended up paying one extortion threat before calling the police after he received a follow-up.

Some found extortion notes — threatening letters, demanding large sums of money or else — courtesy Italian gangsters collectively referred to in the press as The Black Hand. Most of the targeted addresses belonged to newly arrived wealthy Italian immigrants, often celebrities or successful business owners. Famed tenor Enrico Caruso was even a victim of the Black Hand’s extortion in 1920. “I laugh, ho ho, to show me myself that I fear not,” the singer claimed, although he ended up paying one extortion threat before calling the police after he received a follow-up.

At right: A typical extortion letter attributed to the Black Hand (Courtesy Mafia Today)

The Black Hand was already a frightening and well-publicized threat by 1913, although the number of incidents were probably less than the press would have its readers believe.

It was under this apprehension, on Valentine’s Day 1913, that a Mrs. Douglas Robinson arrived at her husband’s real estate office on the Upper East Side to open his mail.

Inside one envelope was a single ‘blood-red’ card, which very simply stated:

“This is the red card to remind you that I have not forgotten. When you receive a black card, you will know that the end is at hand. The Master Mind”

What Mrs. Robinson did not know is that this threatening note had been sent to thousands of New Yorkers that very day. And that it had been preceded just a few days before with another ominous card:

“This is to remind you of an incident in your past, and of my enmity. When you receive a red card it will mean I am drawing near. The Master Mind.”

According to the New York Tribune, 40,000 New Yorkers had received such cards in the mail that month. Had Mrs. Robinson known this fact, she might have found safety in numbers and cautiously went about her day. Instead, in a panic, she reached for the telephone and called New York’s police commissioner.

Except not the current commissioner, the ineffectual reformist Rhinelander Waldo. Instead, she called up New York’s most famous police commissioner (from 1895-97), a man who still lived in New York and, oh yes, had been the President of the United States for a few years — Theodore Roosevelt.

Except not the current commissioner, the ineffectual reformist Rhinelander Waldo. Instead, she called up New York’s most famous police commissioner (from 1895-97), a man who still lived in New York and, oh yes, had been the President of the United States for a few years — Theodore Roosevelt.

The Colonel was still licking his wounds from an unsuccessful bid the previous year at reacquiring the presidency, as the head of the newly formed Bull Moose Party. You may wonder how the wife of a real estate broker would have the ready ear of an ex-President, but it is here that I reveal that Mrs. Douglas Robinson (which is how she’s presented in press accounts of this incident) is in fact Corinne Roosevelt Robinson, Theodore’s younger sister. (Pictured at left in 1920, picture courtesy LOC)

“Leave it to me,” he assured his sister and promptly called up detectives Hyams and Hughes to investigate the matter.

Going only upon Roosevelt’s description, the two detectives began scouring the streets for clues. They were certainly quite proud to be working on a case personally passed to them by Roosevelt — probably the most famous New Yorker in America. Their only liability was that they were working only off of Roosevelt’s information — and his sister had overlooked one rather big piece of information.

While wandering through midtown Manhattan, the detectives struck up a conversation with Edward Gireaux, a booking agent of John Cort, one of America’s leading theatrical impresarios. A Seattle entrepreneur enriched by the Klondike gold rich, Cort, unlike his competitors Klaw & Erlanger and the Shuberts, specialized in promoting a national circuit of legitimate theater. No musicals for the Cort Circuit! (The Cort Theatre, on West 48th Street, is still hammering out dramas to this day.)

The detectives were only too eager to tell Mr. Gireaux of their mysterious case, delivered to them by Roosevelt directly. It was only when they informed the agent of the details of the crime that Gireaux must have smiled to himself.

He produced a stack of the very same ‘blood-red’ cards from his pocket. Perhaps he was passing them out to passers-by. The detectives now saw the entire printed content of the card:

“This is the red card to remind you that I have not forgotten. When you receive a black card, you will know that the end is at hand.

I will see you at the Harris Theatre. — The Master Mind”

‘The Master Mind’, starring Edmund Breese, was a ragged melodrama about “a dominant personality in a band of criminals,” premiering that week at the Harris Theatre at 254 W. 42nd Street. The cards had been nothing more than a slightly inappropriate bit of viral marketing.

Below: Newspaper advertisement for the Master Mind. ‘Even the police were thrilled!’

And it worked! The Master Mind played for several months despite some tepid reviews (“headachy to follow“) and was later turned into a film starring Lionel Barrymore. You can read a contemporary novelization of the play here, featuring such delectable bon mots as “You have made your own beds! Now you shall lie in them. Understand that, please! I have said it — I, the Master Mind!”

The star of the play Breese would himself go on to the silent pictures and co-starred in the Oscar-winning All Quiet On The Western Front in 1930.

As for Theodore Roosevelt, he would publish his autobiography in 1913 and by year’s end would embark on a lengthy journey to South America. Corinne Roosevelt Robinson would later dabble in politics herself, backing Warren G. Harding in 1920 and even recording this radio message in support.