Millions and millions of hours of television and film have been made within the five boroughs since the invention of the camera. But have you ever wondered where the very first roll of film was ever shot?

That distinction most likely goes to a nondescript rooftop studio built atop a building at 1729 St. Marks Avenue in Brooklyn. Of course in 1894, Brooklyn wasn’t yet a borough of New York proper, but would be within five years. So I think it’s fair to grant it the title of New York’s first ever film shoot, or at very least, Brooklyn’s first movie.

The idea of moving pictures was barely a decade old by then, still very experimental and produced under controlled environments. Europeans like Eadweard Muybridge had already captured the movements of animals by the early 1890s, and the Lumieres Brothers would have completed the development of the cinematograph, the first successful motion picture camera to gain widespread acceptance in Europe.

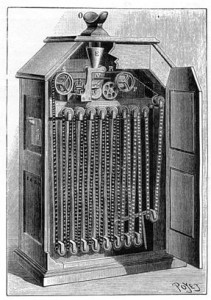

In America, engineers working for Thomas Edison began experimenting with film devices as early as the late 1880s out in his Black Maria studio in West Orange, New Jersey. It was William Kennedy Dickson‘s work for Edison which produced the Kinetoscope, a cabinet peep-show where a rapid flipping of cards created instant movement. An observer would hunch over the box, looking into a view-finder to witness the amazing visual trick contained inside.

In 1893, a completed Kinetoscope made its debut to the world at the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences (the precursor to the Brooklyn Museum). Observers there were treated to the very first American film, Blacksmith Scene.

Above: A poster for a series of Edison kinetoscope films, including a boxing movie or ‘Fight Picture’ (Courtesy LOC)

But that’s not Brooklyn’s only stake in early American film history, thanks in part to another of Edison’s employees named Charles E. Chinnock.

The London-born inventor came to Edison as a telephone electrician and soon moved on to work on other key projects, including the lighting of lower Manhattan via the Pearl Street Station in 1882. Chinnock excelled so ably at his management of the station that, as legend has it, Edison paid him a bonus of $10,000 right from his own pocket. As the electrical grid expanded throughout Manhattan and into the future boroughs, Chinnock was put in charge of the Edison Electric Illuminating Company of Brooklyn, preparing Brooklyn for its own electrical lighting grid.

Like so many of Edison’s employees, Chinnock fell out with the inventor-mogul and left to pursue his own electronic concerns, including the creation of his very own version of the Kinetoscope. In fact, Chinnock would be a minor competitor of Edison’s for the New York Kinetoscope market in the 1890s. While Edison would strike first, Chinnock’s machines would eventually grace the saloons of Coney Island and the lobby of the Eden Musee on 23rd Street in Manhattan.

So obviously, Chinnock would need his own films to exhibit, as Edison would certainly not give permission for his. Chinnock lived in Brooklyn at this time — in a townhouse at Sixth Avenue and St. John’s Place in Park Slope — so it would make sense that his own makeshift film studio would be nearby.

At right: One of Edison’s kinetoscopes. Chinnock’s would have looked quite similar.

In November of 1894, Chinnock began making films for his own version of the Kinetoscope. The place was a rooftop at 1729 St. Mark’s Avenue, a couple miles east from his home, at the edge of today’s neighborhood of East New York.

Chinnock’s rooftop studio was probably similar to Edison’s Black Maria, a small black-walled room built to capture as much natural light as possible. The filming space was very small and could accommodate only a couple subjects. For this reason, boxing became a popular subject of early films because it was compact, thrilling, full of movement and — for its day — rather bawdy.

Edison has already filmed a boxing match, so Chinnock decided to do the same. Two boxers unknown today in the annals of sport — James W. Lahey and Chinnock’s own nephew Robert T. Moore — were chosen to compete, and their battle was captured sometime that November in 1894. The film would have been quickly produced and distributed to Kinetoscope operators.

No copies of the Moore-Lahey faceoff exist today. However, this Edison film featuring the Glenroy Brothers was made just a couple months prior to Chinnock’s old film, so this gives you a good idea of what it could have looked like:

Chinnock continued to rip off Edison films, with his own blacksmith scene, a few dancing girls and even a cock fight.

A few months later, the Latham Brothers, another competitor of Edison’s, filmed another boxing match between Young Griffo and Battling Charles Barnett at Madison Square Garden. This movie holds the distinction of being the first film projected for a paying audience vs. Chinnock’s the soon-to-be-unfashionable kinetoscope.

Chinnock, of course, is no household name. He was eventually run out of the film business by Edison and others. He died in his Park Slope home in 1915.

Chinnock’s real failure may have been a simple one — instead of humans boxing, he should have had cats do it. Just a few months before Chinnock put his nephew in the ring, Edison placed two cats in a ring against each other at the Black Maria studio, in what must certainly be the world’s first LOLCATS video.

In fact, these two were a popular vaudeville act of the day — Professor Welton’s Boxing Cats, named Corbett and Mitchell.

For more on this era of film history in New York City, check out our 2010 podcast NYC and the Birth of the Movies

Chinnock picture courtesy Victorian Cinema

1 reply on “The curious tale behind the first film ever made in Brooklyn”

How wonderfully appropriate for this week as the Left Coast will share the “O’s” with the world this weekend.