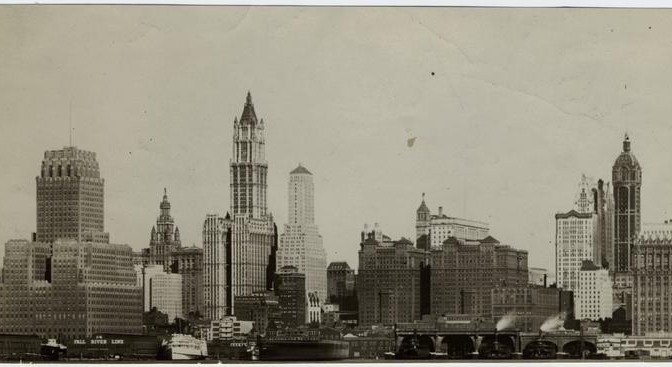

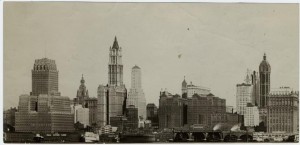

From this angle, you can see two of Cass Gilbert’s creation, the West Street Building and the Woolworth under construction. View of his Broadway-Chambers Building is obscured by the building to the left. (LOC)

It’s Woolworth Building week here in New York City! The lights of Frank Woolworth‘s treasured office tower were turned on in an official ceremony on April 24, 1913, and the building opened for business on May 1.

The five-and-dime mogul reached for one of America’s leading architects in planning his namesake tower. Cass Gilbert had distinguished himself in Minnesota before arriving in New York City in 1899 where he immediately went to work transforming the skyline.

Why was he given such a prestigious assignment to create the world’s largest building? Judging from his work in New York prior to the Woolworth job, there would have been few more qualified than Gilbert to create on a grand scale something so innovative, distinctive to Woolworth’s vision and in keeping with Beaux-Arts values of the day. Unlike another great architect of the day like George Post — whose greatest works have almost all completely vanished — all three of Gilbert’s early New York buildings survive.

Here’s the three buildings that helped him snag the commission for the Woolworth headquarters:

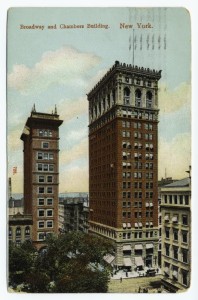

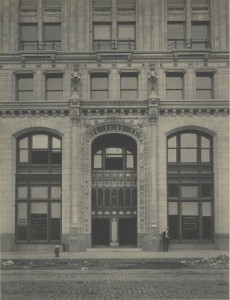

The Broadway-Chambers Building

277 Broadway

1899-1900

Gilbert’s designs for this sturdy tower with a lovely copper top (now, of course, oxidized to green, just like Lady Liberty) featured a mix of brick and terra-cotta, some polychrome, a rarity for its day.

The building’s new tenants required changes to Gilbert’s original plans. The Domestic National Bank on the second floor, who happened to employ a great number of women, required an increase of accessible women’s bathrooms. And the United States Life Insurance Company demanded several large safes be transported to upper floors and installed. Despite the changes, the structure was completed in a staggering four months.

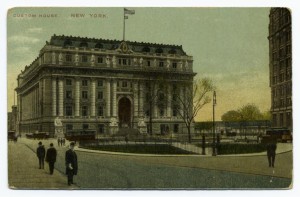

Alexander Hamilton Custom House

One Bowling Green

1902-07

The competition to replace the old Custom House at 55 Wall Street was the impetus that brought Gilbert to New York to create one of America’s finest examples of Beaux-Arts architecture. He was a heavily contested choice, as his designs beat those of New York firms like Carrere and Hastings (later to create a similar building for the New York Public Library).

The seven-story office — more like a monument, really — sits atop the location of old Fort Amsterdam, giving the location a sense of import with its four representative sculptures (by Daniel Chester French) of Africa, America, Asia and Europe. Today the structure houses the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian.

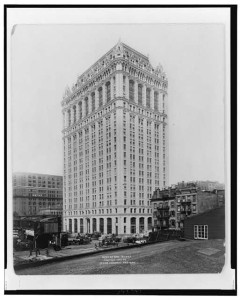

West Street Building

90 West Street

1905-07

But it may have been his 1905 commission to design a waterfront office building on West Street for ferry operator and asphalt king Howard Carroll that secured his reputation as a virtuoso of the skyscraper age. The building, to serve port and railroad industries of lower Manhattan, had Manhattan’s highest restaurant on its top floor. At the time, this was shorefront property; today it stands across from Battery Park City.

Gilbert would dabble in themes and styles with the West Street Building that would be further explored with the Woolworth Building. No other building shares as many features with the Woolworth Building as this one. Former rival John Carrere admitted, “If my opinion counts for anything I think it is the most successful building of its class.”

Below: the West Street Building, the side facing into Manhattan.

Pictures courtesy NYPL.

1 reply on “What a resume! Cass Gilbert’s three stunning prequels to the Woolworth Building”

The Manhattan skyline that appears in the first picture was a late 1920s picture (1927 or 1928) because in this picture appears the Art Deco Barclay Vesey of 1926 and, next to Woolworth Building, can see the Transportation Building of 1927.