A genuine survivor: The building to the right was once the Strangers Hospital in the 1870s. This picture, by Berenice Abbott, was taken many decades later, in 1937. And the building is still around today! (Picture NYPL)

New York used to lump the sick, the poor and the homeless into one mass of needy unwanted. Since its founding, the city has struggled take care of the growing dual problems of poverty and plague, but in a way that kept the unwanted safely invisible to its wealthier classes.

With the rise of immigration starting in the 1840s, the problem became too pervasive to simply throw people into large catch-all institutions like Bellevue Hospital (which, in its early years, served as almshouse, hospital, quarantine, prison and morgue). Soon Blackwell’s Island became the solution, with a string of grim institutions lining the East River island.

Below: For those less ‘worthy’, a cold night might have meant sleeping in the local police station. In the illustration below (1877), the homeless are turned out into the street at morning’s light. (NYPL)

Another solution for the homeless arose in 1870s in the delirious days of the scandals of the Tweed Ring. John H. Keyser made his fortune in the growing new field of indoor plumbing; in fact, he seemed to be wildly successful at it, a sudden millionaire in an era were certain men — with certain connections — grew wealthy overnight.

Keyser may have had friends in high places, but he expressed an unusual need for the common man. Perhaps his outreach was a tad cynical; the poor he helped often voted the way Keyser preferred. But with the city facing a severe poverty crisis, even the baited gesture had beneficial results.

The plumber king operated a ‘Strangers Rest’ at 510 Pearl Street in 1869, a boarding house for vagrant men and women. The vagrant house was situated halfway between City Hall and Five Points, and it operated on that spirit as well, an abode of good will and a little favoritism. You could stay if you were deemed “worthy,” meaning either good behavior or an unofficial pledge of allegiance to the Democratic Party.

The following year, Keyser purchased a building for $8,000 owned by the New York Dry Dock Company and transformed it into the Strangers Hospital, a vagrant home and care center in the vastly crowded Lower East Side. The building is still standing today at 143-145 Avenue D. Across the street is the Dry Dock Playground.

The Strangers Hospital opened in January 1871 with dozens of bed in several wards, a reading room, Russian and Turkish baths, a recreation room, and a chapel, with walls made of “India rubber, to avert the absorption of any infectious materials.”

An opening day blessing announced its unique mission: “It is not intended for the benefit of the wealthy, who in times of sickness can command the comforts of a well-ordered home and the attendance of a skillful physician or surgeon. Nor yet the beggar, who leads a life of dissolute idleness, rotating in winter and in sickness about the charitable institutions of this city. It is intended for the succor and restoration of the deserving poor……strangers — strangers to the home of plenty and comfort in which they have been born and nurtured, and from which misfortune and disease have parted them.”

In other words, you were worthy if they deemed you to be so.

It was an odd differentiation. As an accommodation for up to 200 people, it served not only as a regular treatment hospital for the ‘deserving poor’, but as a convalescent home and halfway house. Most likely, you had to be recommended but a tenant in good standing and, as I mentioned, it probably helped if you were a Democrat.

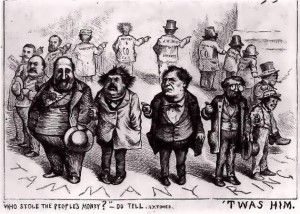

I underscore that because the Strangers Hospital didn’t last very long, closing in 1874. And this is why — Keyser was known as the ‘Ring Plumber’, a crony of William ‘Boss’ Tweed who enjoyed thousands of dollars in kickbacks and special favors. Tweed went to trial in 1873 for his crimes, and his cronies, although never formally charged, were disgraced.

Below: Keyser would have been one of the links of this chain of favoritism, envisioned by illustrator Thomas Nast

Contemporary sources of the day are not kind to Keyser, with one account call him “a real live Oily Gammon [arch-villian, from an English phrase which meant fatty ham], an Americanized specimen of the article — revised and improved in order to fit him to be a bright and shining light in the fraternity of which he is a member.”

By 1877 Keyser went bankrupt. Still, his obituary lists several more philanthropic efforts by Keyser, including a “free eating house” in Washington Square in 1888. From the headline: “Thousands were aided by Man Accused to Being Tweed’s Partner.” So whether or not his actions were sincere, he did manage to fund the feeding and caring of thousands of poor and sick New Yorkers. Where does such a legacy stand?

2 replies on “The Strangers Hospital: Your special home on Avenue D, brought to you by Boss Tweed’s plumber king”

Great writeup! Always glad to learn about NYC from the Tweed era.

One note: “The building is still standing today at 143-145 Avenue D” – the link takes you to a location in Queens.

Thanks! Corrected the link. Originally it tried to send me to an address in Texas….