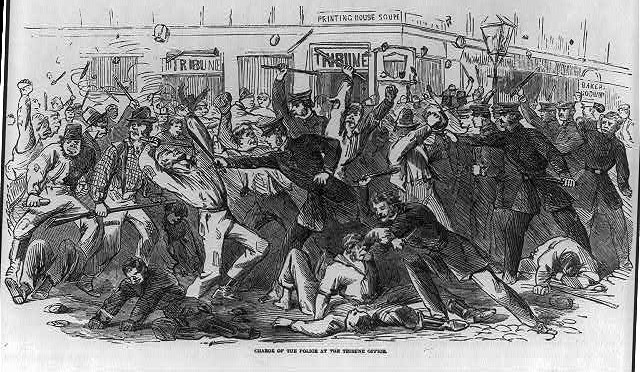

Police try to restore order in front of the New York Tribune building, a pro-Lincoln publication being attacked by rioters.

Why are there no permanent remembrances of any significant kind in New York City to the Civil War Draft Riots? It was the most grave, the most tumultuous event in New York City history between the Revolutionary War and September 11, 2001. Doesn’t it merit some mention?

The leading answer, of course, is that New Yorkers don’t end up looking very good. This isn’t New York’s finest moment; in fact, it’s probably its worst. Many of the hundreds who died during that week were rioters, lawbreakers, killers. The racism of many was laid bare, exposed brutally. On the first day of rioting, firemen — the Black Joke Engine Co. — were actually complicit in kicking off the violence. Even the leaders of the period had ulterior motives.

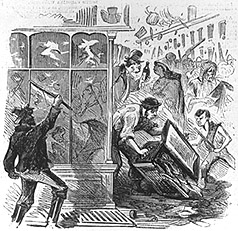

At right: The Black Joke firemen help plunder the draft office

For almost five days, the angered and the desperate rampaged through the streets of New York. The violence was only superficially fueled by anger over the actual conscription act, an excuse to vent other frustrations, some understandable, others reprehensible. For several days, nobody was safe — from the moment the Ninth District Draft Office was incinerated on Monday morning to the final sweep of barricaded streets by state militia and federal troops on Thursday night.

It’s a complicated, ugly, confused time in New York City history. But how does a city acknowledge a self-inflicted tragedy? Who wants to remind America of how duplicitous many New Yorkers were during the Civil War?

The Draft Riots are a nuisance of fact, sometimes serving to obfuscate the sacrifice of the many thousands of New Yorkers who gave their lives in service of the Union Army. New York holds up its reputation as a melting pot, as a place where people of different ethnicities co-exist, if not always peaceably. The images of the Draft Riots — black families fleeing the city in terror, lynched bodies from trees and streetlamps — serve only to remind you that the spirit of inclusiveness is merely a modern notion and possibly a mirage.

Anniversaries are important. They reflect how we want to present our past and illustrate our present frame of mind. On the one hundredth anniversary of the sinking of the Titanic, people re-watched the James Cameron movie and took a (strangely morbid) memorial voyage along the same watery path the original ship was to have taken. On the centennial of the Triangle Factory Fire, hundreds marched through the street and chalked memorials on the sidewalk in front of the homes of the victims.

On America’s bicentennial, New York briefly awoke from its bankrupt, gritty slumber to present a shimmering display of patriotism featuring Queen Elizabeth, festive parades, and battalions of ships in the harbor. Every September, we revisit the horror and suffering of the attacks upon the World Trade Center because the idea of forgetting about it is simply unimaginable.

The Draft Riots fit none of the criteria of something we’d like to remember. It’s for that reason we should.

Today we remember the Civil War in iconic terms, good and evil, right and wrong. The Draft Riots presents a nuanced reinterpretation of that story line. It places New York City not outside the significance of the battlefield, but squarely within it. The Union was not united, but an assortment of different viewpoints. That Lincoln and the Union Army succeeded is even more remarkable when you realize the dissension from within.

For that reason, I hope one day the city of New York will take upon itself to memorize this event in the same way it has so many others. Until then, I’m at least grateful to those various private institutions around the city who will ensure that future New Yorkers will continue to be stunned, horrified and otherwise amazed at the extraordinary events which took place in this city on July 13-16, 1863.

———–

According to this article from the New York Times in 1963, there were once three temporary plaques placed in significant places for the centennial marking — at Fifth Avenue between 43rd and 44th (site of the Colored Orphanage), Third Avenue and 46th Street (site of the Ninth District Draft Office) and, oddly, at Tenth Avenue and 46th Street (site of the home of Willy Jones, the first person chosen in the draft lottery). I do not believe these plaques to still be in existence, but if you know otherwise, please email me.

Here’s a few ways to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the Civil War Draft Riots over the next few days:

Reading: I highly recommend Barnet Schecter‘s “The Devil’s Own Work: The Civil War Draft Riots and the Fight To Reconstruct America“. For a more academic analysis, you can also try “The New York City Draft Riots: Their Significance for American Society and Politics in the Age of the Civil War,” by Ivar Bernstein.

Exhibit: There are no Draft Riot exhibits currently in New York, but the Metropolitan Museum of Art has two must-see shows about the Civil War that would make a fine substitute — ‘The Civil War and American Art’ and ‘Photography and the American Civil War‘

Discussion: The Museum of the City of New York is presenting a panel discussion on Monday, July 15, with a superb line-up, including Craig Stephen Wilder, filmmaker Ric Burns, historian Joshua Brown and author Kevin Baker. Check here for more information.

Podcast: Then of course there’s our 2011 podcast on the Civil War Draft Riots. You can find it on iTunes or download it from here. And I’ve finally uploaded it onto SoundCloud, so you can listen to it right here!

And if you’d like more information on how the Draft Riots affected the future boroughs of New York City, you can check out my article on Huffington Post: The Many Civil War Draft Riots: Violence From 150 Years Ago, in New York and Beyond.

NOTE: If you know of any events relating to the Draft Riots, please email me and I will include them in the list above. Thanks!

1 reply on “It’s the 150th anniversary of the 1863 Civil War Draft Riots. Why should we care?”

Perhaps the Draft Riots were the high-water mark, if you will, of sheer terror in the streets of New York, which no one was immune from– but if you want a horrifying needless tragedy with several times more loss of life, and devastation of an entire community, you’d have to say the General Slocum shipwreck. The Riots may have scared people, but they were in fact escapable for those not directly in its path. The Slocum, sadly, was not escapable for most of those aboard, and a wholesale emptying of many tenement buildings in the Tompkins Square neighborhood was a much more solemn reminder of the sheer random chance of a death, of a sort to be dreaded, inexplicably befalling the seemingly undeserving.