New York City Hall and its brand new water fountain, in 1846, courtesy Currier and Ives (LOC)

KNOW YOUR MAYORS A modest little series about some of the greatest, notorious, most important, even most useless, mayors of New York City. Other entrants in the Bowery Boys mayoral survey can be found here.

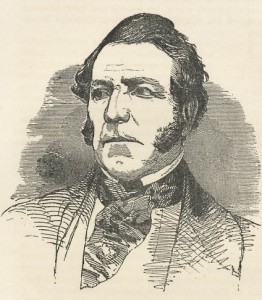

Mayor Andrew H. Mickle

In office: 1846-1847

New York City has had many useless and incompetent mayors. To be fair, that legion of forgettable and unspectacular men is bloated by the ways in which mayors were chosen in the early days.

Before 1783, mayors were assigned to the city by the governor of the New York colony. The hand-picked mayor presided over a board of aldermen that were elected by the people. He operated at the behest of the British crown, often overseeing a group very much opposed to British rule.

This curious arrangement carried on even after the Revolutionary War, with New York governors continuing to assign mayors to the city until 1821, when the Common Council (today’s City Council) received the authority to appoint mayors themselves.

The role of mayor was not powerful at this time. Before 1821, they were essentially a mouthpiece for the will of the state government. After 1821, mayors were beholden to the Common Council for their very existence. The job frequently went to well-liked merchants with unsullied reputations, uncontroversial men who rarely rocked the boat.

When the New York state charter was amended in 1834, mayors became popularly elected. (The first was Cornelius Lawrence, in a violent, chaotic election.) But this did not necessarily alter the quality of office holders. Mayors now became the puppets of both powerful council members and thriving political machines like Tammany Hall. Corruption ensured that the position of mayor be considered a valuable but neutered prize.

Further minimizing their role in 1834 was the reduction of the mayoral term to one year (until 1849, when they were given two). Even the most savvy and adroit politician would wither in frustration under these limitations. Men questing for substantive political power sought other prizes. The office of mayor became, in essence, a beauty pageant.

And thus enters into the picture one Andrew H. Mickle, tobacconist and mayor of New York City from 1846 to 1847.

Andrew was born in 1805 to a Scottish couple in New York’s Sixth Ward, the future Five Points. Of course, this was in the era when Collect Pond was being drained, and new residences around this area weren’t yet considered notorious slums. However it seems later biographers gave his back story a bit of that Five Points patina. “He was born in a shanty in the ‘bloody aude Sixth’, in the attic of which a dozen pigs made their habitation,” claimed Gustavus Myers.

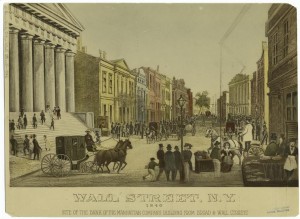

As a young man, he began working for the tobacconist George B. Miller at Water and Wall Streets. He would eventually fall in love with Miller’s daughter, marry her, then take over the business entirely.

Below: Wall Street in 1846. Mickle’s tobacco shop would have been located in the distance, near the tree. (NYPL)

A 40-year-old tobacco seller might not fit the profile of mayoral candidate today, but it did in 1845. The mayor of New York at the time was sugar manufacturer William Havemeyer, who had actually tried doing something in office (namely, reforming the Common Council), to the consternation of Tammany.

With a surge of immigration adding new voters, Democratic leaders looked for a relatable candidate, somebody who was “one of the people,” but one with little political motivation. These were the years of the Native American party, a drive to flush America of the thousands of Irish immigrants who were arriving in New York. Mickle, though fully unsuited for a life of politics, represented the opposition, the surge of new voters and the core of the Democratic party.

It also helped that Andrew, with his modest upbringing, was known as the son-in-law of a popular tobacco concern, one that many political men visited on a weekly basis.

But if we are to believe the eyewitness of Nathaniel Hubbard, Mickle’s entry into city politics was engineered almost entirely by a different source — his mother-in-law.

Mrs. Russell* was one of the most powerful women in early Tammany Hall history. She was known, according to Hubbard, for giving her employees the day off at the tobacco counter, “a holiday for electioneering purposes,” the writer claims.

Desiring a bit of power for herself, Mrs.Russell essentially bribed Tammany Hall. “She sent a letter to the rulers of Tammany with a pledge to give them $5,000 on condition they would nominate and elect her son-in-law to the office of mayor of this city,” wrote Hubbard.

At right: The first Tammany Hall, at Frankfurt and Nassau Streets, their first official home after moving from Martling’s Long Room

Perhaps it says something about the office of the mayor that Tammany Hall took the bait willingly, placing this non-entity Mickle at the top of the ticket. Political machines, especially in the early years, felt strongly about holding offices, with few concerns about who went into them.

Hubbard describes Mickle as “an uneducated man,” with abilities of “a very common order.” But in 1845, perhaps, a man of middling skills could properly govern, if he represented the right things. And so Andrew Mickle was resoundingly elected, receiving more votes than his competitors in the Whig and Native American parties combined.

For somebody accustomed mostly to cigars, Mickle did not embarrass himself in his new task. Tammany Hall was pleased with their purchase; Mickle would be considered a “tried and conservative Democrat.” Hubbard would only say that Mickle “passed through his duties … quite satisfactorily to the political party which elected him.” [source]

He exhibited no amount of political acumen, nor was any required of him. The city prospered of its own accord under Mickle. Telegraph poles began appearing in this city in 1846, connecting New York with Albany and Washington DC, and New York’s first great department store, owned by A.T Stewart, opened that year, just a block from City Hall. Richard Hoe‘s innovation of the rotary press that year revolutionized journalism.

Mickle encouraged the construction of a new workhouse and insane asylum, leading eventually to Blackwell’s Island becoming a sort of one-stop for all of New York’s undesirable industries. After the Great Explosion of 1845, Mickle also saw to developing New York’s fire-fighting infrastructure, although it would remain in the hands of private operators until the 1860s.

He announced his retirement at the end of his term in 1847 and retired once again to the world of tobacco, officially renaming the family business A. H. Mickle & Sons. He remained well-liked in Tammany circles up until his death in 1863.

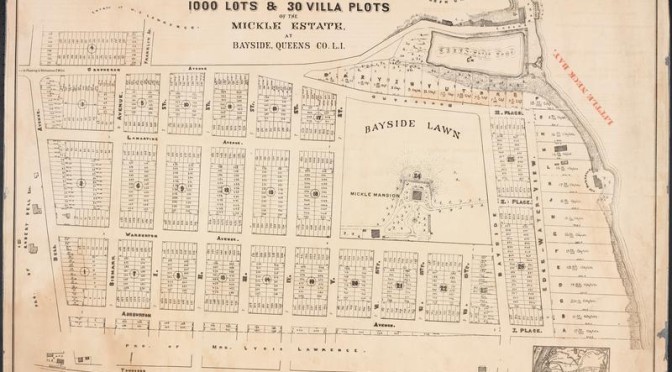

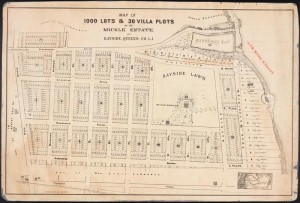

As a curious side note to his later life, Mickle took up residence in the area of Bayside (today, the neighborhood of Bayside, Queens), “situated on one of the most commanding elevations in that section of Long Island.” His spacious manor here was called Bayside Lawn. Many years after his death, in October 1890, the mansion was destroyed in a fire.

Below: A map of the Mickle estate (MCNY)

*I have no clue why she’s Mrs. Russell and not Mrs. Miller, but I’m still researching this fact.

EDIT: An earlier version of this story stated that Mickle was preceded as mayor by Philip Hone. In fact, it was William Havemeyer.

2 replies on “Meet Andrew H. Mickle, perhaps the least qualified man to ever serve as the mayor of New York City”

Wow! Less qualified than David Dinkins?

[…] history blog Bowery Boys writes about Andrew H. Mickle, a son of Scottish immigrants, downtown tobacco merchant, and an unremarkable Tammany puppet who […]