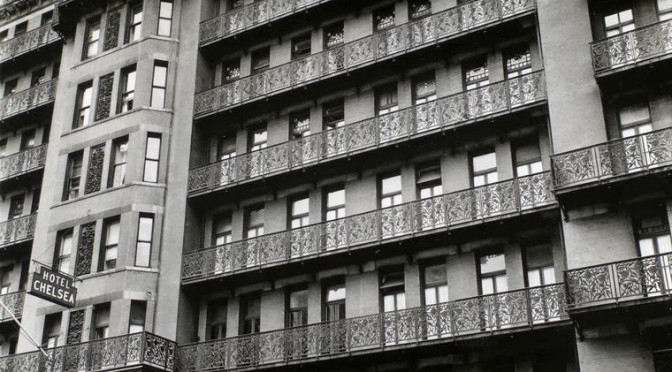

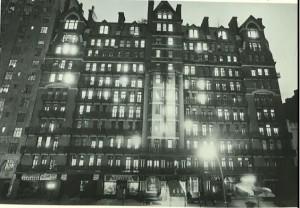

The Hotel Chelsea, August 1936, photograph by Berenice Abbott (NYPL)

Inside the Dream Palace

The Life and Times of New York’s Legendary Chelsea Hotel

by Sherill Tippins

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

Few places in New York exist with so many ghosts as the Chelsea Hotel. Oh, I don’t know if it’s really haunted, but the historical figures that have gained inspiration from their stays at this storied place have certainly left their mark. Â But with geniuses — with the pressure of being genius — also comes drama, escapism, and tragedy.

Sherill Tippins‘ new book on the Chelsea Hotel — aptly named Inside the Dream Palace — does double-duty as a hall of fame for great substance-abusing artists and writers. Â It’s a wondrous, colorful account of a unique social living experiment as it slowly dismantled its pretensions and became a rustic den of creativity, community and debauchery.

All the great tales are recounted here — from Dylan Thomas‘s death to Sid and Nancy‘s tragic evening — and a many new ones introduced. Â For all the names I expected to see (Henry Miller, Arthur C. Clarke, Thomas Wolfe, Patti Smith), there were a great many more that have surprising connections to this unique landmark.

I had such a fantastic time sampling the lives of the Chelsea’s various characters that I wanted to ask the author a few questions myself. Â Here’s Sherill Tippins, elaborating upon the hotel’s unusual origins, its tenacious spirit and uncertain future:

Reading of the original philosophies behind the Chelsea Hotel – the utopic, if somewhat simplistic notion of communal living of various types of classes – I kept thinking ‘Wow, imagine if somebody tried floating this idea today!â€Â What was it about this period and this project specifically that made people open to such a radical suggestion?

ST:  In the wake of Boss Tweed’s thefts, the long, deep recession of 1873, and the usual massive shift of wealth to the top one percent that followed (sound familiar?), the city’s social fabric seemed to many New Yorkers to be irredeemably destroyed.  People were so desperate for some kind of workable solution that New Yorkers from different economic classes started meeting in unprecedented ways – “bankers sitting next to bakers,†as one reporter put it in amazement – to discuss what had happened to the city and how it might start to recover.

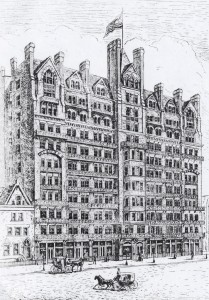

Into this critical moment in history walked the Chelsea’s architect, Philip Hubert. Basically, Hubert appealed to New Yorkers in the same way every successful idea man has in New York, before or since – via their pocketbooks.  (Below: The Chelsea, photographed by the Wurts Brothers, NYPL)

He introduced the concept of cooperative living – showing how much cheaper it was for New Yorkers to form a “club†to buy their own land, build an apartment house to their own liking, and share the costs of maintenance, fuel, and other services.  The new cooperative apartments were so appealing and cheap that the demand for them proved nearly insatiable.

Here was a way to bridge the stultifying divide that had opened up between classes in a society where status was determined by the size of an individual’s bank account, so that citizens felt compelled to isolate themselves, as Hubert put it, “to guard their dearly cherished state of exaltation.†New Yorkers who lived together, on the other hand, would have to converse and exchange ideas. Alliances would form, and perhaps these alliances would arm groups against the chicanery of the next Boss Tweed.

To create real diversity, Hubert had to make cooperatives not only practical but, in a sense, sexy.  He managed that feat with the Chelsea Association Building, set in the heart of New York’s racy theater district, at the intersection of all the new elevated railroad lines and equidistant from the Ladies’ Mile shopping district and the decadent Tenderloin.  To make life at the Chelsea even more enticing, he built a cooperative theater and a drama school to go with the cooperative, and invited in an assortment of artists, musicians, actors and writers to spice up the core population of businessmen, financiers, and working people.

You walk us very vividly through different decades of the Chelsea’s strange and storied existence. If you could re-visit a particular era of the Chelsea yourself, to which time period would you like to see? Its earliest days, the wild 60s, or another era?

ST:  Every time I’m asked this question I respond differently, because in fact I love every era at the Chelsea. Today, though, I’ll choose the Depression era as the one I’d most like to experience.

It was a surprisingly idyllic time at the hotel.  Room prices had lowered to a level that artists could actually afford, and secondly because many residents experienced a new kind of creative freedom as they were subsidized financially by the W.P.A. (“I can’t begin to tell you how rich everyone was,†one artist recalled.)

This was the era when the residents laid down a set of “house rules†that have been followed, more or less, ever since: don’t interrupt people during work hours; don’t visit without an invitation; don’t hit up famous neighbors for a job or a connection, and so on.  With their privacy protected, working artists felt comfortable socializing after hours: Edgar Lee Masters entertaining Thomas Wolfe in his suite, Masters and the artist John Sloan listening to music on the Victrola together, Van Wyck Brooks dropping in for cocktails with Sloan….  It was from these interactions that a real, lasting Chelsea Hotel culture was born—a culture that would nurture generations of artists in the decades to come.

From ‘Dream Palace’: “The artist Brion Gysin and his close friend William Burroughs arrived to market their new invention, the Dream Machine.”

You’ve written about so many iconic writers and artists, both in this book and in your past projects. And this is really a story of icons, as they pass through this extraordinary landmark.  But I greatly enjoyed stumbling upon some of your rather obscure figures here, those fairly forgotten today. Any particular individuals that you newly discovered in your research that were a particular favorite of yours?

ST: Â One of the most fascinating longtime Chelsea Hotel denizens, who is known surprisingly little considering his cultural contributions, is the anthropologist-musicologist-artist-filmmaker-occultist Harry Smith (at right). Â Smith created The Anthology of American Folk Music, a collection of powerfully resonant American blues, ballads, gospel, and other songs that helped inspire the 1960s folk music movement and that inspired Bob Dylan in particular.

At the Chelsea, in his role as house magician, Smith provided the Yippies with a magic spell for levitating the Pentagon and Leonard Cohen with a love spell to seduce the singer Nico. (It failed, sadly.) Smith was also an experimental filmmaker, considered a genius by the underground film community; his films were designed to affect viewers neurologically, presumably altering their state of consciousness as a path toward further evolution. In the 1970s, Smith created a film, Mahagonny, based on the opera by Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht and featuring such Chelsea Hotel residents as Patti Smith, Robert Mapplethorpe, and Allen Ginsberg—a film intended to communicate to all cultures, regardless of language or location, humanity’s troubled state.

There are others I found captivating, even if they weren’t known outside their small circles of admirers.  In fact, I would have included hundreds more if I’d only had the pages to contain them.

There’s also a large amount of tragedy associated with the Chelsea, from the most famous events (Dylan Thomas and Sid Vicious, of course) to even the footnotes of history, those known only for their awful ends. For instance, the woman who cut off her hand and jumped off the roof. (I went back and read that sentence like six times!)  Did you sense any particular reason for this in your research? Is it just the density of dramatic figures that stayed here?Â

ST: I’m so glad you asked that question, because I’ve asked it myself so many times!  Unfortunately, I’ve never come up with a definitive answer, but I can give you my hypothesis.

Somehow, from the beginning—according to the letters and other writings in various archives—the Chelsea has always felt feminine to those who have lived in it.  Feminine and maternal, like a mother welcoming her children into her arms.  I would imagine that if one were in a state of existential despair or psychological extremity, one might look for comfort to an architectural (archetypal?) mother figure, particularly as one made the ultimate decision to end one’s life.

I’m thinking of Frank Kavecky, the impoverished young artist who was robbed on the subway of funds he was holding for the Hungarian Sick and Benevolent Society.  Discovering his loss, he went straight to the Chelsea – checking into a room for the afternoon, locking the door, settling himself into a rocking chair, and shooting himself in the head.

And Almyra Wilcox, the well-to-do visitor who overdosed on pills while writing a love letter to someone she knew she’d never see again. She was found dead the next morning, unfinished letter in hand.  Reading these stories, I think, if I were ready to do myself in, I might choose the Chelsea.  Wouldn’t you?

Photo by Claudio Edinger (courtesy Ed Hamilton/Living With Legends)

The fate of the Chelsea Hotel remains undecided, sitting empty, “like a corpse in its niche on Twenty-Third Street.â€Â If you could somehow dictate the future of the Chelsea yourself, what would you like see happen here? A return to its transient roots or an entirely new purpose altogether?Â

ST:  Of course, the obvious desire would be to bring back the old days, with the former co-owner Stanley Bard managing the Chelsea and his son, David Bard, waiting in the wings. But since life is about moving forward, I would hope that the new owner, Ed Scheetz, will respect the Chelsea’s traditional function as fully as he claims to do.

The new owner has some intriguing ideas for the “new†Chelsea: creating a small, urban MacDowell-colony type program in which a half-dozen artists would enjoy free room and board, along with space on the ground floor to display or perform finished work.  He has shown me his plans for placing large, expensive rooms next to small, relatively cheap ones, to encourage a mix of people in the traditional Chelsea Hotel way.  He has assured me that he intends to maintain the building as a hotel, with the much-needed circulation of daily visitors from around the world, along with permanent residences whose occupants can pass on the community’s memories and values.

All of this sounds wonderful. The challenge, as always, lies in making this culture both “real†and affordable. It’s ultimately my hope that Ed Scheetz will be willing to go so far as to make the Chelsea the loss leader of his collection of New York hotels, if that’s what it takes to keep the life of the Hotel Chelsea going.

_______________________________________

Sherill was also on the Leonard Lopate Show on WNYC, talking about the book. Here’s the show (and thanks to Chip Pate on Twitter for pointing this out!):Â

Other recent selections from the Bowery Boys Bookshelf:

1 reply on “The wonder of the Chelsea Hotel: ‘Inside the Dream Palace’ — an interview with author Sherill Tippins”

With all due respect to all types of life styles, how do you expect a 78 year old dowagger to live next to a Sid Viscious type. That’s just one example of the “traditional function.” I’m all for getting along but some “mix of people” will never get along. Who’s going to be the judge of the contents? Multiculture and tolerance has limits.

Love the Bowery Boys!