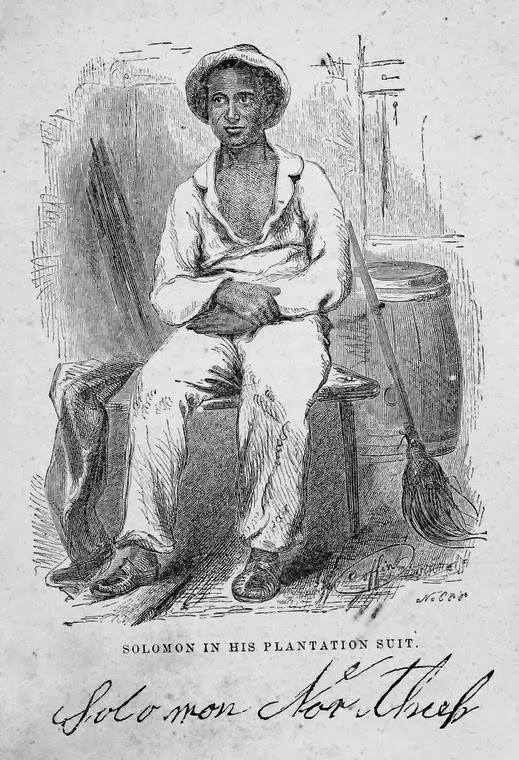

An engraving featured in Solomon Northup’s narrative Twelve Years A Slave, published in 1853.

The New York farmer and musician Solomon Northup was sold into slavery in 1841, tricked by two supposed members of a circus troupe, promising Northrup work in their traveling show. Instead, Northrup awoke in bondage, eventually smuggled to New Orleans where he faced years of cruel servitude under a variety of plantation owners. After regaining his freedom in 1853, he wrote the narrative Twelve Years A Slave, his harrowing account of his years in the South.

The book became a best-seller within Republican abolitionist circles, released a year after Harriet Beecher Stowe‘s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. It was certainly in the possession of Henry Ward Beecher, Harriet’s younger brother, who turned his Brooklyn pulpit at Plymouth Church into a sounding board for abolitionist ideas. (One hundred and sixty years later, the Oscar-nominated film version of Twelve Years A Slave, starring Chiwetel Ejiofor as Northup, played at Brooklyn Heights Cinema, located one block away from Beecher’s church.)

Northup and his family lived in upstate New York, but New York City proper plays a small but ominous role in his narrative. Lured by the promise of employment by two men named Brown and Hamilton, Northup travels from home in Saratoga, first to Albany, then to New York itself:

“They hurried forward, without again stopping to exhibit, and in due course of time, we reached New-York, taking lodgings at a house on the west side of the city, in a street running from Broadway to the river.”

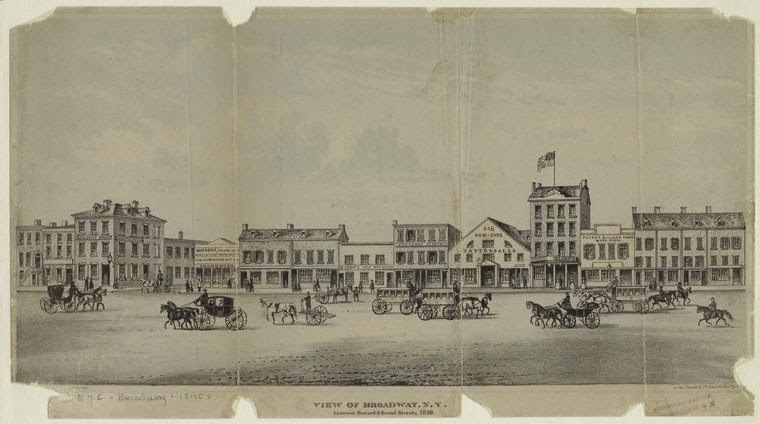

Below: A view of Broadway (between Howard and Grand Streets) in 1840. To the south of this view was Canal Street and Five Points.

“I supposed my journey was at an end, and expected in a day or two at least, to return to my friends and family at Saratoga. Brown and Hamilton, however, began to importune me to continue with them to Washington. They alleged that immediately on their arrival, now that the summer season was approaching, the circus would set out for the north. They promised me a situation and high wages if I would accompany them.

Largely did they expatiate on the advantages that would result to me, and such were the flattering representations they made, that I finally concluded the offer.”

Northup agrees to accompany them further north to Washington DC. It would be there that Northup would be drugged and sold into bondage by his two nefarious companions. But before they leave New York, they suggest that Solomon perform a certain task, curious given the subsequent events which occurred:

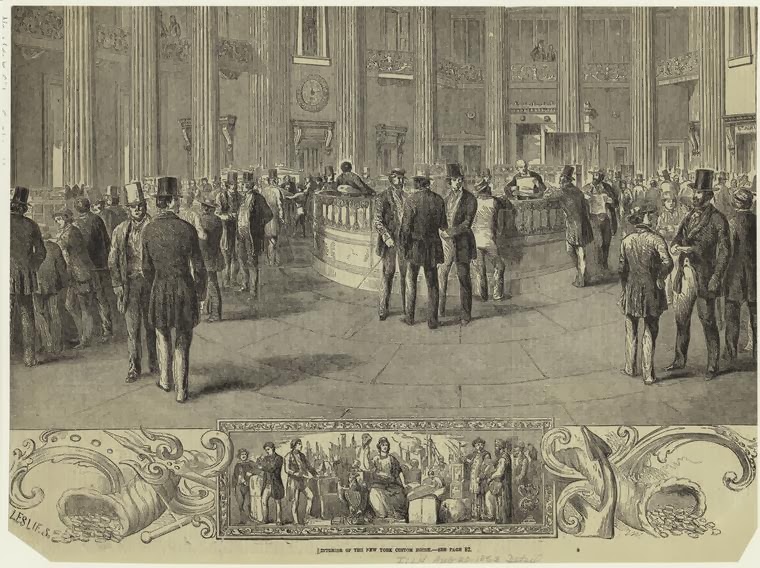

“The next morning they suggested that, inasmuch as we were about entering a slave State, it would be well, before leaving New-York, to procure free papers. The idea struck me as a prudent one, though I think it would scarcely have occurred to me, had they not proposed it.

We proceeded at once to what I understood to be the Custom House. They made oath to certain facts showing I was a free man.”

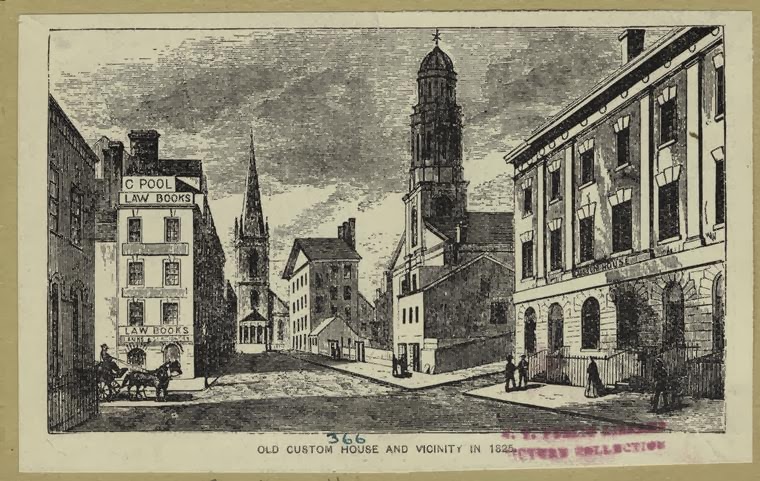

Why is there a little confusion in Northrup’s statement regarding the Custom House? Perhaps because the building he would have visited — at 22-24 Wall Street — was in its final days as New York’s Custom House, an office which had grown far too small for the task. The following year, New York’s new Custom House would have at last been opened at the other end of the block — the building that is today’s Federal Hall.

Below: Northrup and his associates would have entered the building at the far right of this illustration (which depicts Wall Street in 1825)

“Some further formalities were gone through with before it was completed, when, paying the officer two dollars, I placed the papers in my pocket, and started with my two friends to our hotel. I thought at the time, I must confess, that the papers were scarcely worth the cost of obtaining them – the apprehension of danger to my personal safety never having suggested itself to me in the remotest manner.”

Below: The interior of the New York Custom House, 1853

All images courtesy New York Public Library

After its publication in 1853, Northup’s account would be available for sale in certain New York bookstores for several years. But keep in mind New York’s divided loyalties to the South; it would not have been a universally popular read here in the city.

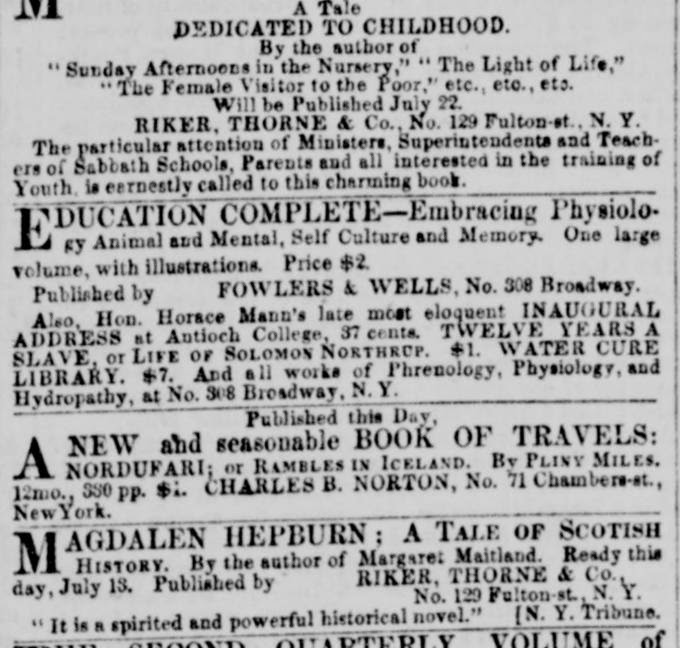

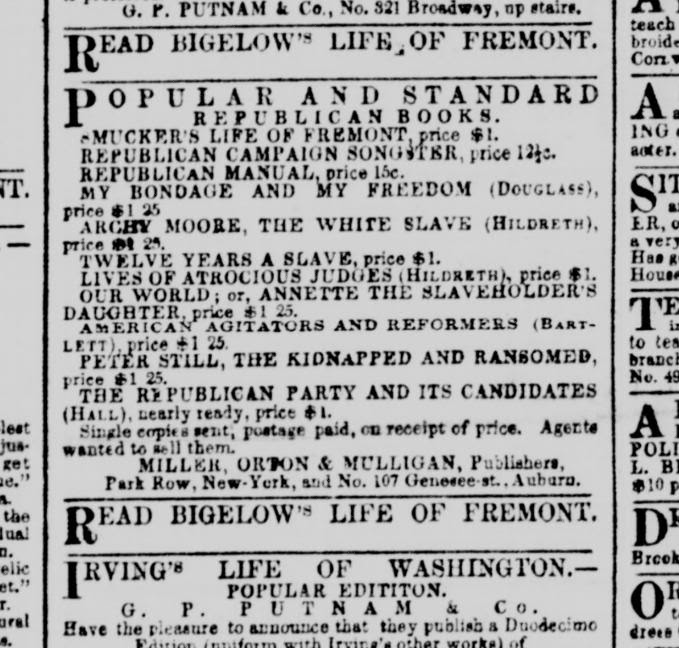

Below: the book for sale in 1854 at a bookstore at 308 Broadway, and in 1856, at a Park Row bookseller, both ads from the New York Daily Tribune