We once lived in a world when cocaine was in nearly everything — pain relievers, muscle relaxers, wine, fountain drinks, cigarettes, hair tonics, feminine products. It was therapeutic, a “nerve stimulant,” a natural remedy and an over-the-counter drug sold in a variety of forms and doses. The coca plant, to many, was “the most tonic plant of the vegetable world.” [source]

The coca byproduct popped up in a variety of medicinal and recreational forms in the 1880s. In particular, New Yorkers were wild about cocaine, especially those in the medical community.

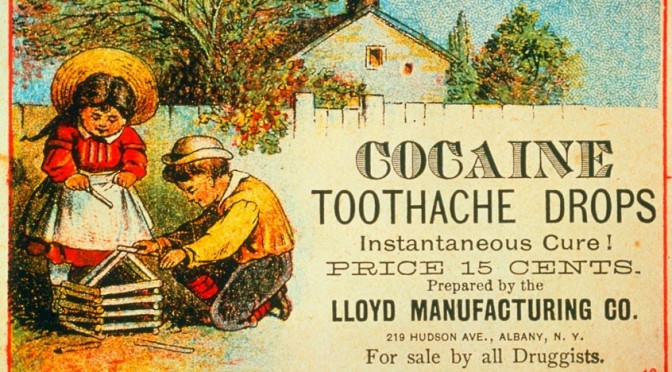

“The therapeutic uses of cocaine are so numerous that the value of this wonderful remedy seems only beginning to be appreciated,” said the New York Times in 1885. “The new uses to which cocaine has been applied with success in New York include hay fever, catarrh and toothache and it is now being experimented with in cases of seasickness.” They later report that even asthma could be eradicated by it.

Cocaine was the wonder drug of the early 1880s. Not only could it cure disease; it could also dampen the senses. In 1884, a doctor presented his findings at the College of Physicians and Surgeons (23rd/Park Avenue), heralding the successes of “anesthetic cocaine” in numbing patients during ear and eye surgeries. It was even given as a pain reliever to horses.

A cocaine ad touting its use for “female complaints, rectal diseases”:

By the 1890s, cocaine would be used as an anesthetic in a variety of cases, even injected directly into the spine. As a miracle solution, “[t]hen came cocaine to claim her crown.” [source]

There was even a cocaine district in lower Manhattan — around the cross streets of William and Fulton — where more of the drug was produced than perhaps any other place in the United States, by such manufacturers as McKesson & Robbins (95-97 Fulton Street) and New York Quinine & Chemical Works (114 William Street).

Below: Helmbold’s Drug Store on Broadway and 17th Street, in Ladies Mile, would have sold a host of cocaine-related products in the 1880s. (NYPL)

“Cocaine looked to be the saviour of doctors the world over,” wrote author Dominic Streatfeild in his book Cocaine: An Unauthorized Biography, “but, apart from its use as an anesthetic in surgical procedures, it was not really curing anything; it was just making people feel great for awhile.”

By the mid-1880s, there seemed to be little doubt of cocaine’s habit-forming qualities, but there were some notable holdouts. William A. Hammond, the Surgeon General for the United States during the Civil War, didn’t think so, frequently experimenting upon himself and later batting away concerns from some notable Brooklyn doctors.

“At first I injected one grain and experienced an exhilaration of spirits similar to that produced by two or three glasses of champagne,” he told a newspaper in 1886.

But medical professionals soon grew weary as their hospitals and asylums soon filled with cocaine addicts, many who supplemented their habits with opium or morphine.

“No medical technique with such a short history has claimed so many victims as cocaine,” reported the New York Medical Record in 1887.

Sometimes it would be the doctors and nurses themselves that were trapped “in the clutches of cocaine.” (The Cinemax show The Knick depicts this disturbing conflict within its main character, Dr. John Thackery, who at a certain point injects the drug straight into his penis and between his toes.)

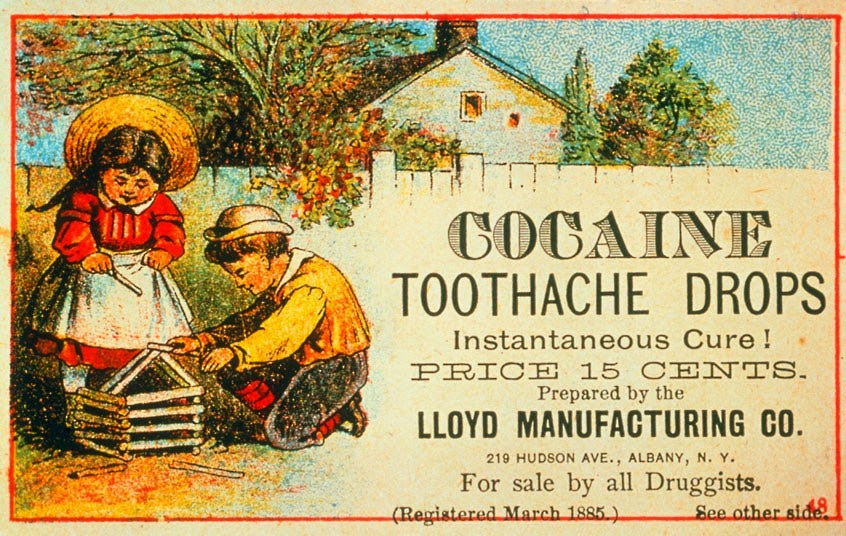

At right: A 1900 ad for an at-home drug therapy program provided by the St. James Society. Interestingly, this was located on Tin Pan Alley and near the heart of the pre-Times Square theater district!

From a cursory perusal of newspaper from the late 1890s, one can find a notable doctor or two succumbing to drug addiction almost once a month. “COCAINE KILLS A DOCTOR,” blared a headline from January 2, 1898. Another physician “WAS CRAZED BY COCAINE.” went another in 1895.

The euphoria over cocaine was over. The number of cocaine addiction cases blossomed through the 1890s, just as moralists and social reformers were looking to eliminate vice from city streets. In 1893, the first law aimed at cocaine (along with morphine, opium and chloral) made it available only by prescription which, like so many later pharmaceuticals, was merely a speed bump for the serious user.

Hysteria soon followed. Cocaine was associated with crime, with occultists, with loose women, with poor people, with African-American, Asians and Jews. Here’s a rather startling quote from a druggist in 1895: “[W]ith the exception of a few abandoned white women, its use is confined almost exclusively to the colored folk.” (Several years later, the New York Times took this assertion to the next level.)

Meanwhile, newspapers seemed only concerned with the numerous rich, white addicts. And, of course, the many innocents who were lured by dealers on the streets and playgrounds.

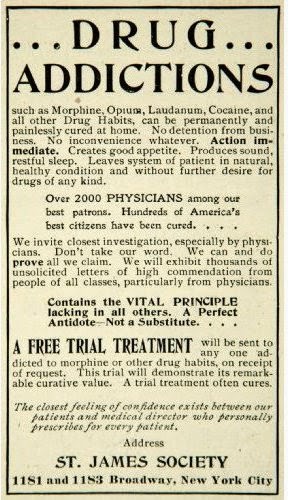

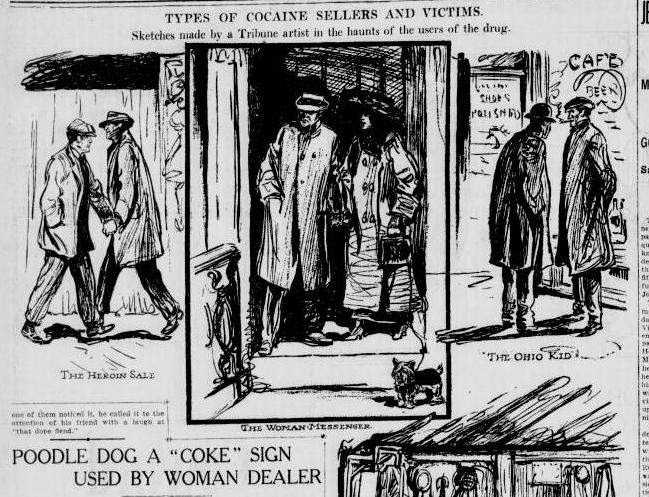

Below: An illustration from the New York Tribune, 1912. A 1907 law prohibited most sales of cocaine over the counter, creating an illicit ‘street market’. The Tribune dramatically displays the ways in which cocaine and other drugs were sold. Note the headline underneath it!

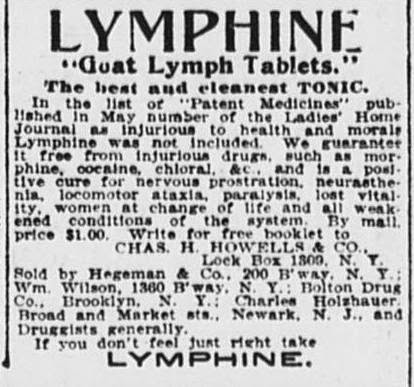

Although still a legal substance, most products began advertising themselves as an alternative to cocaine. In 1895, you might find products that touted cocaine as a pain reliever; ten years later, medicines were now proclaiming they were cocaine-free.

Below: A 1904 ad for “goat lymph tablets” reminds its readers that its free of “injurious drugs.”

It would take several years to make cocaine entirely illegal. During the 1910s, those who wanted it could make arrangements with a pharmacist, forge a prescription or, when all else failed, just rob the warehouses which stored cocaine.

In 1911, the drug was now a “poisonous snake,” “the perfect intoxicant of the devil,” its original uses in the United States now entirely forgotten and replaced with safer, less addictive alternatives. (Dentists, for instance, would discover Novocaine.)

A series of local and federal laws in the mid-1900s assured that cocaine and other habit-forming drugs would be ushered off the market within the decade.

The Harrison Narcotics Tax Act, passed in 1914, imposed stiff taxes on coca and opiate products, virtually eliminating any legal market for the drugs and insuring its manufacture and distribution be driven underground.

And just in time, too, for Prohibition was just around the corner!

1 reply on “The cocaine fiends of the Gilded Age: New York stages an intervention for its over-the-counter drug problem”

Medicine was in its infancy so thankfully there was something! If it wasn’t abused though I could still go out and buy some really good ‘tooth tablets’, ‘cough syrup’, and ‘analgesic cream’