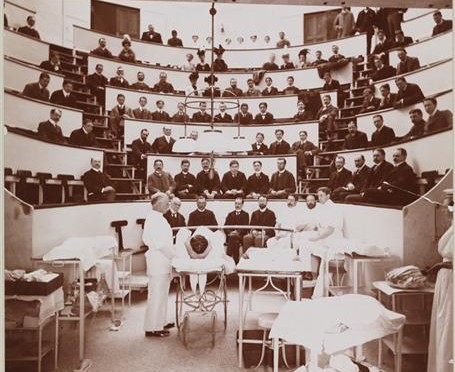

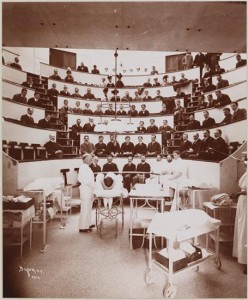

Syms operating theater at Roosevelt Hospital in 1900, perhaps one of the cleanest places in Manhattan! (Picture courtesy Museum of the City of New York)

It was not a fair fight.

In 1895, in celebrating the innovative new surgery building at Roosevelt Hospital, the New York Times decided to compare its revolutionary new features to an antiquated hospital, one that had been serving patients for decades in that metropolis right across the water — Long Island College Hospital in Brooklyn.

Upon its opening in 1892, William J. Syms Operating Theater, west of Columbus Circle, was a jewel in the crown of the Roosevelt Hospital complex, employing the latest antiseptic techniques, even using materials in its construction that were believed to be less germ prone — glass operating tables, a mosaic floor, iron chairs.

New rules of cleanliness were employed within its surgical theater. “[The visitor] will see everywhere signs of the most exquisite cleanliness. [He] will see no sign of haste or confusion, of dirt or litter, of human pain or suffering.”

Its appearance may be familiar to you if you’re watching the medical drama The Knick on Cinemax which depicts a medical theater of similar design.

Below: The inside of the Syms operating room from 1893: (Scouting NY)

In heralding this sparkly new institution, the newspaper decided to throw a vaunted, albeit older, one under the bus.

“In the operating theater of the Long Island College Hospital the conditions obtain [sic] today are more in keeping with the practices of half a century ago. The large and ugly theatre is fitted with wooden benches, upon which generations of students have done their whittling. The floor beneath the benches acts as a convenient and frequent receptacle for tobacco juice. The walls are tinted with a dirty, bluish color, and on the side nearest the operating table there is an ominous stain of seepage from the floor above.”

The description continues rather grotesquely — I’ll get to more of it in a second — but is it a fair characterization?

While disquieting to our modern understanding of cleanliness, in fact, the Brooklyn institution was certainly deteriorating, but probably in better shape than most places of this type in America in the 1890s.

The Tale of Long Island College Hospital

The story of Long Island College Hospital is the tale of the neighborhood of Cobble Hill, Brooklyn.

Well before south Brooklyn was urban-planned into a grid of respectable blocks, the area that is today’s Cobble Hill was called Ponkiesberg, much of it the farmland of a man named Ralph Patchen. Near the eastern edge of his property sat the ruins of the old Revolutionary War fort . [You may remember this fort from our ghost stories podcast from last year.]

Patchen’s farm was purchased by Joseph A. Perry, later known for his contributions for planning Green-Wood Cemetery. Â On this former lot he built a sumptuous mansion which stood at Henry Street, between Amity and Pacific (pictured below).

Meanwhile, on the edge of his property, two doctors recently arrived from Germany opened a clinic exclusively for Brooklyn’s small, but emerging German population. In the late 1850s, they and other prominent doctors sought to found a college hospital and purchased the Perry mansion in 1858.

From this old house sprang the roots of Long Island College Hospital. While the United States already had a few medical schools, this was America’s first college hospital — on-the-job training as it were, with students interacting directly with patients.

Below: Faculty and students of the medical school pose on the steps of the Perry Mansion, LICH’s principal structure in the mid-19th century

It was an institution quite well known for innovations in the late 19th century.

Many of America’s finest physicians passed through here at some point in their storied careers.

The clinician Austin Flint brought many European techniques to the school, including the stethoscope, a variant of which making its debut here. (Flint actually has a heart murmur named after him, too.)

In 1888 the Hoagland Laboratory opened on campus, providing facilities for both research and education that kept Long Island College Hospital at the forefront of medicine.

In many ways, it was still a respected institution in 1895, but they were often in debt and in desperate need of an upgrade.

Its conditions were probably not unlike most medical institutions of the day, but it paled in comparison to the spectacular new operating theater built for Roosevelt Hospital as a gift.

The Tale of Syms Operating Theater

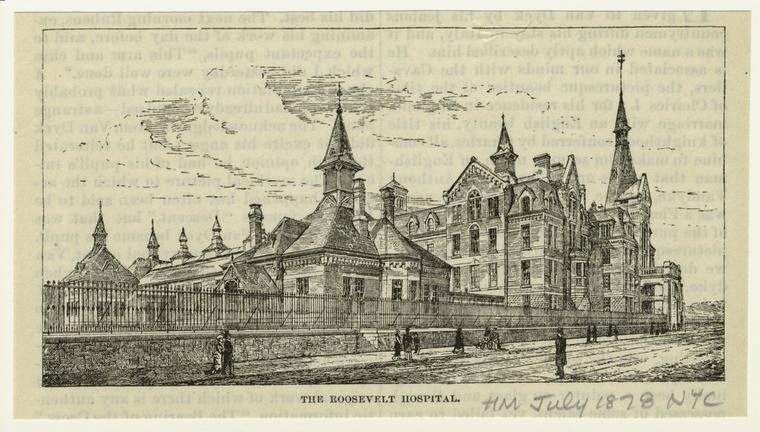

Roosevelt Hospital (pictured above) was born out of the generosity of James H. Roosevelt, a wealthy philanthropist confined to his manor for most of his life by illness. When he died, he bequeathed his entire fortune to the creation of a new hospital in his name. Roosevelt Hospital’s first building opened in 1871, over ten years after the opening of Long Island College Hospital.

Many years later, another wealthy benefactor — gun merchant William Syms — benefited from a successful operation at Roosevelt Hospital and donated most of his fortune to the hospital, with the specific intent of building a new operating center.

When Syms Operating Theater opened in 1892, the press trumpeted its sleek innovations in sanitation, creating a brightly lit, aseptic environment previously unseen except in a few places in New York.

It was perhaps the cleanest place in Manhattan or, at least, it was touted as such.

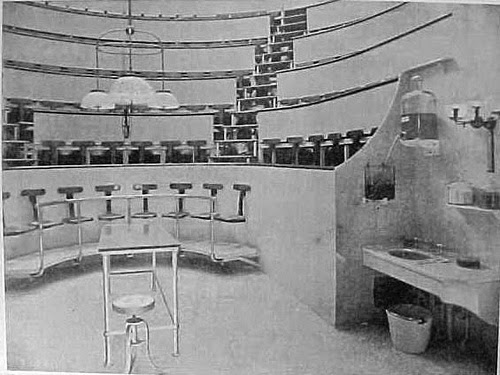

From a citation by the Landmarks Preservation Commission: “Aseptic operating rooms were bright, clean, hard, undecorated spaces; they were the ‘high tech’ spaces of their day.”

Below: The sleek interior of the Syms Operating Theater, 1925. (Picture courtesy Museum of City of New York)

This was not simply for the health of patients and staff. A building of such profound innovations — such as a moat around the basement for thorough drainage — was meant to ease the tensions of New Yorkers who considered operating rooms barbaric and even obscene.

Disturbing descriptions

The administrators at Long Island College Hospital could not have been thrilled when they picked up the New York Times on April 27, 1895.

Right there on the front page was a horror story with their historic institution as a backdrop.

“It is from this upper floor that foul and inexpressibly nauseating odors are wafted through the operating theater at all times, because it is there that the students of the college and hospital practice anatomy on eighteen or twenty decomposing cadavers.”

The reporter noted the routine delivery of dead bodies from room to room and the grim procedures of dissection witnessed by dozens of disinterested students.

“In spite of the rising temperature, which should render dissection almost impossible in a building exclusively devoted to the purpose, it is plain from the stench that the hot weather had not stopped the students of Long Island College Hospital.”

Due to the proximity of the autopsy theater to regular patients, “whatever ills result from breathing such a tainted atmosphere must be shared to a lesser extent by the surgical patients of the hospital.”

Sepsis was an omnipresent and growing.danger. As if to confirm this, the hospital refused to provide its mortality records.

The renown doctor Alexander Skene, perhaps the best known physician at the hospital, blamed a lack of funding for the institution’s woes.

“The people of Brooklyn are to blame in some measure because they do not give the hospital the financial support it needs and merits,” said Skene. “The school is very prosperous, while the hospital is very much the reverse.”

(Skene, a leader in the field of gynecology, died just a few years later. Today you can find him in bust form in Brooklyn’s Grand Army Plaza.)

Aftermath

The regents of Long Island College Hospital responded with disbelief, even outrage. “I am there everyday, and I never feel any smell,” said a chairman. “We have the plans all ready for a new operating room … but we have no money.”

Fortunately, the hospital and its patients were rescued from further embarrassment by Caroline Polhemus, the wife of one of the hospital’s regents Henry Ditmas Polhemus.

When her husband died that year in 1895, a society matron donated a sizable chunk of her fortune to create the Polhemus Memorial Clinic (pictured at right) in her husband’s honor.

All autopsies for educational purposes were moved to the top floor of the clinic, across the street and far away from the hallways regular hospital.

The building is still around — you can see it here — although it is no longer associated with the hospital.

The Syms Operating Theater served Roosevelt Hospital for several decades before it, too, was declared inadequate.

That building is also still around however; Scouting New York has a nice feature on its current whereabouts, a must-see stop on any New York medical-inspired walking tour.

It’s safe to say that both hospitals are held in high regard in the annals of medical history.

But while Roosevelt Hospital is still going strong.– it’s now an affiliate of Mount Sinai — the end is near for Long Island College Hospital, as the community and staff fight to keep it open after years of battles with its owner the State University of New York.

Follow along at Curbed for the latest developments on the LICH front.

![[Roosevelt Hospital, Sym's Operating Room.]](https://boweryboyshistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/MNY68242-300x242.jpg)

1 reply on “The tale of two hospitals: Enjoy the “inexpressibly nauseating” aromas of Brooklyn’s oldest operating theater”

This is fascinating history about the hospitals in NYC. The standards of cleanliness have certainly changed immensely from what they were a century ago. It’s a welcomed sign of progress we might not always think about.