The World’s Fair of 1964-65 at Flushing Meadows-Corona Park was a major American event forward-looking in its intent and, in many ways, backwards in its practice. In particular, Robert Moses did not care for cheap carnival amusements, nor did he care for music or art that was particular edgy or controversial. Moses’ tastes ruled supreme over the Fair as he held veto power over any works that were in “extreme bad taste or low standard.”

There was no pavilion dedicated to art although several independent partners funded their own art displays. The New York State Pavilion presented the work of brand-new pop artists; an objectionable piece by Andy Warhol entitled Thirteen Wanted Men was eventually painted over (although it was the governor Nelson Rockefeller who objected in this case).

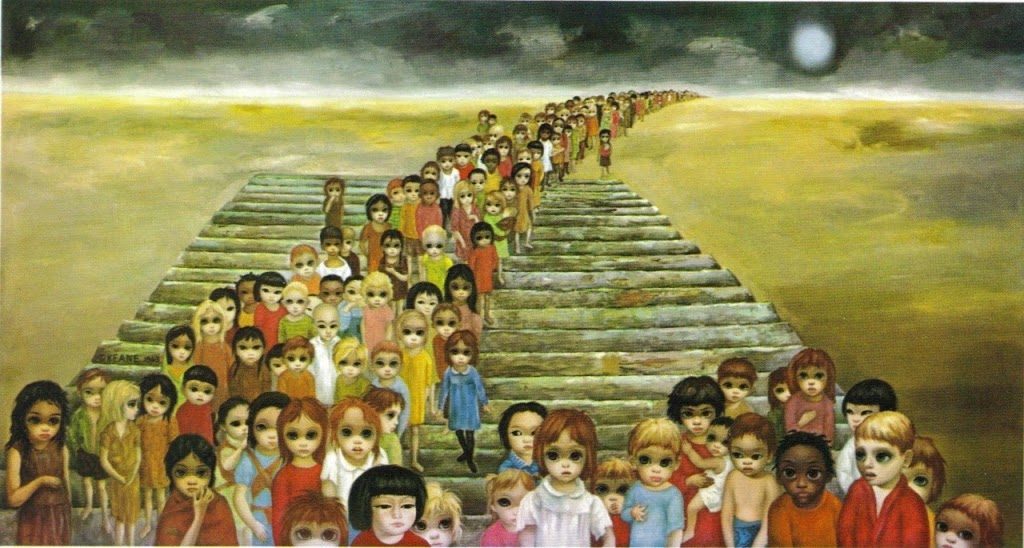

Moses did eventually throw out one surprising piece of artwork — Tomorrow Forever by Margaret Keane.

The Keane painting was to have been displayed in this building at the fair.**

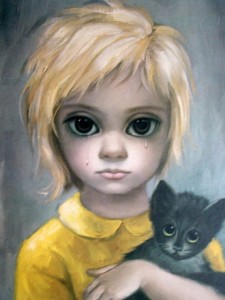

Keane was known for her bizarre and haunting images of children and animals with large, empty eyes. During the 1960s, her husband Walter Keane claimed to be the creator of her paintings. It was he who was announced as the painter of this macabre work, chosen in February 1964 to grace the Fair’s Hall of Education. The venue devoted to the future of schools would feature a scale model of an elementary school from the year 2000, a playground with “futuristic climbing structures,” and from the entranceway, the terrifying painting you see above.

The work by Keane, representing “something which would be symbolic for the aspiration of children,” was not exactly heralded as the pinnacle of artistic expression in 1964.

The New York Times’ art critic John Canaday could barely conceal his disgust at this “grotesque announcement,” adding, “Mr. Keane is the painter who enjoys international celebration for grinding out formula pictures of wide‐eyed children of such appalling sentimentality that his product has become synonymous among critics with the very definition of tasteless hack work.” [source]

To be fair, Canaday had only seen a photograph of the painting, which depicts an endless sea of soul-crushing zombie children rising out of a morose and barren wasteland. “That’s true,” he confessed to a Life Magazine reporter. “It’s normally a principle of mine never to judge just by a photograph, but in this case, it didn’t matter.”

Moses seemed to agree with Canaday, demanding the Hall of Education cancel the planned installation before it was even mounted. Thanks to Canaday’s protest, Moses’ office was inundated with letters from angry intellectuals and aesthetes. “[T]he perpetrators of this art burlesque,” wrote Joseph James Akston, “expose us to veritable scandal sure to incur ridicule and laughter of the whole civilized world with possible exception of Russians.” [source]

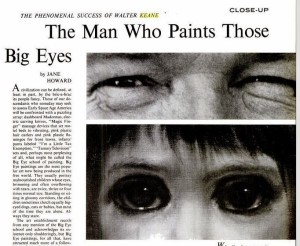

Keane, who of course didn’t paint the artwork attributed to him, nonetheless seemed to revel in the critical potshots. The following year, he issued a press releases from San Francisco and Tahiti, declaring himself “the American Gauguin.” Canaday would continue to take aim at Keane’s kitschy work. Imagine how Canaday felt when he discovered that Walter hadn’t even painted the works he so deliciously despised?

Margaret eventually left her husband and sued for rightful ownership of her artwork.

Below: From a Life Magazine profile in August 1965:

NOTE: I’m being a little irreverent in calling the painting “terrifying” as the artist clearly intended the subjects to be starving, sad children. However, the passage of time has been a little strange to Keane’s legacy. She is perhaps more beloved than ever — there’s a new Tim Burton film coming out this year — but the flagrant sentimentality of the work has given way to their spectacular kitsch value.

** The Hall of Education picture courtesy the blog Little Owl Ski which has a few other nifty World’s Fair pictures.