New York Fashion Week, the city’s twice-yearly celebration of couture and runway, traces its roots to a 1943 press week event at the Plaza Hotel, organized by publicist Eleanor Lambert. But there had been a variety of one-off ‘fashion weeks’ or American fashion events in the years between the wars. In 1934, the Mayfair Mannequin Academy, a local modeling school, even petitioned Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia to declare an official New York Fashion Week as a way to encourage American designers who worked in an industry dominated by Paris.

But well before any of those events, New York’s most famous runway show took place on the street — the Sunday promenades along Fifth Avenue. It was especially robust during Easter with wealthy women trying to outdo each other in latest styles from Europe. Newspapers covered Easter Sunday with the same fervor as a modern fashion show, noting colors, hem lines, and even the plumage flagrantly bursting from hats.

While there was no dedicated ‘fashion week’ one hundred years ago, there was heightened and excited attention to of-the-moment fashion trends. So here’s a little thought experiment — what would an actual Fashion Week in 1915 look like?

There would in fact be fashion-related events at Madison Square Garden (in its original location off of Madison Square) so let’s put this imaginary Fashion Week there:

An End to Bondage

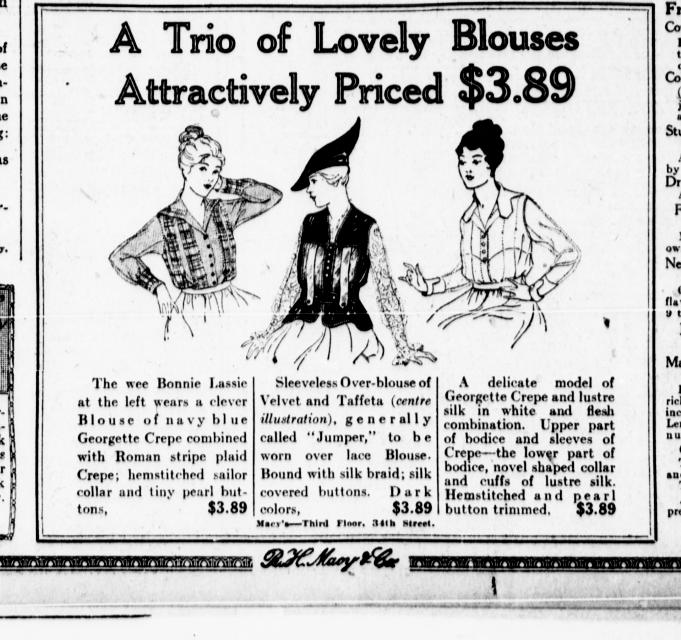

Women’s fashion would be affected by the war in Europe in many ways. Travel restrictions put an end to the constant flow of fashion queues from Paris. New ideas that were strictly American could begin influencing the way women dressed here.

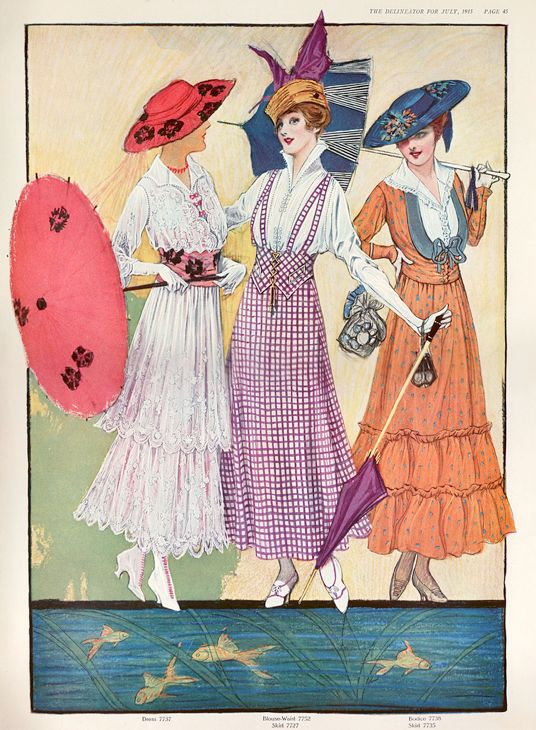

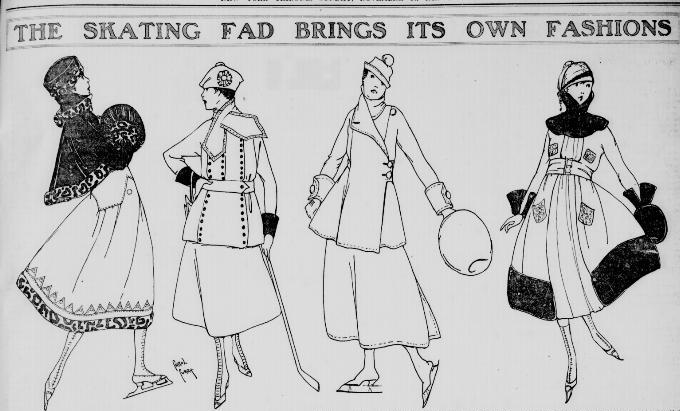

The growing independence of women also allowed for a looser, more comfortable style. Gone from the streets were the dreaded hobble skirts, limiting the ability of women to take long strides. (Anything for fashion!) What audiences might have seen in 1915 were skirt styles that opened up at the bottom, allowing for freer movement.

These would come to be called ‘war crinoline’, essentially a precursor to a modern conservative skirt and described as bell-shaped, a “very full calf-length skirt” requiring extra fabric to attain its flowy, romantic look.

This would seem to be antithetical to wartime thinking — when lifestyles were often pared back — but these larger gowns were touted as practical fashion and thus ‘patriotic’ in their intent. The role of women in wartime, many thought, was to simply look their best. At least, this was the line many fashion designers took during the era.

Revolutionary Undergarments

While some women would continue to subject themselves to the corset, the practicalities of life soon led to its unpopularity. In 1914, Carisse Crosby, a well-connected society heiress from New Rochelle, received the patent for a revolutionary new form of support — the modern bra. Called the backless brassiere, the invention further facilitated a departure from stiff and uncomfortable silhouettes.

Crosby (really named Mary Phelps Jacobs) was a well connected society woman and would have been milling about the crowd at Madison Square Garden. In 1915 she married the Boston Brahmin playboy Richard Peabody and eventually moved to Manhattan when she became pregnant with his child.

The Gradual Straight Line

Perhaps the boldest fashion transition in the 1910s was the subtle shift from curvaceous, hour-glass forms to a straight, shapeless silhouette. While the war crinoline still required a narrow waist for some of its dramatics, competing styles leaned towards sleekness. This was an evolution from the Empire waist which had gained a resurgence earlier in the decade.

Rise of the Dangerous

The predominant form of women’s fashion in the 1920s — the boyish flapper with sleek dresses and short hair — would rise from the edgier look of the ‘vamp’, best embodied in the late 1910s by film and stage actress Theda Bara. This took the reformed instincts of woman’s fashion to its extreme. Sexuality became more overt and stylized, from bold makeup to exposed flesh. This was certainly not the look of your average lady on the street, but soon slight shades of the vamp style would eventually seep into everyday fashion.

The Popularity of Make-Up

It was unseemly of women to paint their faces with too many cosmetics during the late 19th century. But by the mid 1910s, women were influenced by actresses and dancers, and taboos against wearing cosmetics were relaxed. The natural pale complexion so desired a decade earlier gave way to a kind of democratization that only makeup could provide. Women were allowed to heighten the drama in their faces and mask the imperfections.

In 1915, two major forces in women’s beauty opened salons on Fifth Avenue — Elizabeth Arden and Helena Rubenstein. Both heavily influenced by the Parisian fashion aesthetic, elite New York women flocked to their shops. Within a decade, these two entrepreneurs would be the anchors of a burgeoning and highly lucrative beauty industry.

Hints of the ‘Little Black Dress’?

Black was not worn by women of gaiety and glamour. It was strictly the hue of mourning during the Gilded Age and rarely made an appearance in actual evening wear. However in an imagined fashion show in 1915, you may have seen a slight hint of it here or there, although not very practical and only as part of bold ‘vamp’ styling of its time. It might have seemed edgy and even a bit bizarre, something only a worldly woman might have worn.

It would take another decade — and the influence of Coco Chanel — to bring the black dress into fashionable prominence. It would eventually becoming one of the defining looks of the New York woman.

Driving Attire

The continued popularity of the automobile required specific sorts of fashion to protect the clothes from dust. These items found their way into regular wear. This article from an August 1, 1915, issue of the New York Sun proclaims the return of the smock. “The smock is worn in the garden and on the golf links.”

Still A World of Hats

One taste that didn’t wander far was the love of hats. While flamboyant hats still topped many society ladies head, styles eventually became a little serious with nautical and even military influences.

Even the school girls got into the act of fashion! Here’s a pair from the first day of school in 1915….