On the afternoon of October 13, 1914, a bomb exploded in the northwest corner of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, sending deadly iron shrapnel flying through the room.

A stained glass window was shattered and an 18-inch hole (shown in the picture below) was blown into the floor. While the pews were partially filled with worshipers, there was only a single injury, to a boy whose head was grazed by a piece of flying metal.

That was the second bomb of the day; another explosive, downtown at St. Alphonsus Church on West Broadway, detonated a little after noon.

Such a disturbing attack in a public space would cause mayhem in the streets today. Yet this sort of terrorism was disturbingly frequent one hundred years ago, a tactic used by anarchist groups to sow discontent.

Many of the attacks were primarily aimed at New York’s financiers. For instance, on July 4, 1914, a brownstone exploded on the Upper East Side in the Yorkville neighborhood, killing members of the Anarchist Black Cross. The explosives had accidentally gone off and were intended for the home of John D. Rockefeller.

No arrests had been made in the St. Patrick’s attack. But detectives working with the New York Department of Combustibles were on the case, and, in March of 1915, they managed to thwart a second attack on St. Patrick’s with the help of a young detective named Emilio Polignani.

Polignani was only 25 years old. He had been a patrolman for only a few months when he was chosen in the fall of 1914 for a special assignment — to infiltrate anarchist circles and identify the perpetrators of the attack on St. Patrick’s.

His qualifications, according to the New York Times, were “his nationality, his newness to the force and most especially because Captain Tunney had decided that he had the nerve and the resource to carry him through tight places.”

St. Patrick’s Cathedral 1923

For four months, Polignani lived under cover (possibly not even allowed to speak to his wife) as Frank Baldo, attending anarchist meetings throughout the city, becoming familiar with several of the more radical members. It was in Yorkville that he became friends with an 18-year-old named Charles Carbone.

From the New York Times: “Carbone and Polignani became intimate and used to take long walks together, in which Carbone, according to the detective, inveighed against the rich and suggested bombs as a means of readjusting social inequalities.”

Polignani was even initiated into an anarchist group by swearing an oath administered “on the cross hilt of a dagger to bind him … to his comrades.”

Carbone confided to Polignani details of the botched July 4th bomb meant for Rockefeller. “I am an expert,” he said. “Nothing like that could happen to me.”

Forms part of: George Grantham Bain Collection (Library of Congress).

On Christmas the detective met another anarchist named Frank Abarno who later professed the wish to bomb St. Patrick’s.

Over the next two months, the three men walked along the East River and plotted a new attack at St Patrick’s, seen as the ultimate representative of both religion and wealth.

What Abarno and Carbone did not know was that Polignani sent pages from their bomb manual down to police headquarters.

Plans were finally hatched in late February to again bomb the cathedral. The men gathered explosive materials at a tenement on Third Avenue then wandering around the church the Saturday before, looking for a more effective spot in which to place an explosive. Their movements were closely followed by other disguised detectives, clued in by Polignani of the anarchist’s plans.

The new attack on St. Patrick’s Cathedral was planned for March 2nd. Abarno and Polignani left the Third Avenue tenement that morning with bombs placed under coats and armed with cigars to be used to light the fuses. (Curiously enough Carbone failed to show up; he was later arrested.) They headed towards the cathedral which was filled with hundreds of worshipers in the middle of morning Mass.

Luckily, Polignani had alerted his department of the details of the bomb attack. Waiting for them at St. Patrick’s were dozens of disguised detectives, so many that a Broadway theatrical costumer was employed to fashion the various false appearances.

“Of the fifty [detectives] stationed in the Cathedral,” said The Evening World, “[s]ome were disguised as women worshipers, two as scrubwomen, others as ushers.”

When Abarno prepared to light the fuse on the bomb with his cigar, one of the scrubwomen “suddenly straightened up and seized [Abarno] by the arm.” Another detective calmly strolled over to the lit bomb and pinched out the fuse. The Mass went entirely uninterrupted. (Read the breathtaking details of the capture here.)

Polignani kept up the facade for most of the interrogation, and his would-be conspirators were none the wiser. He argued with Abarno in jail, eventually getting him to talk openly about his involvement (to the delight of detectives who were listening in).

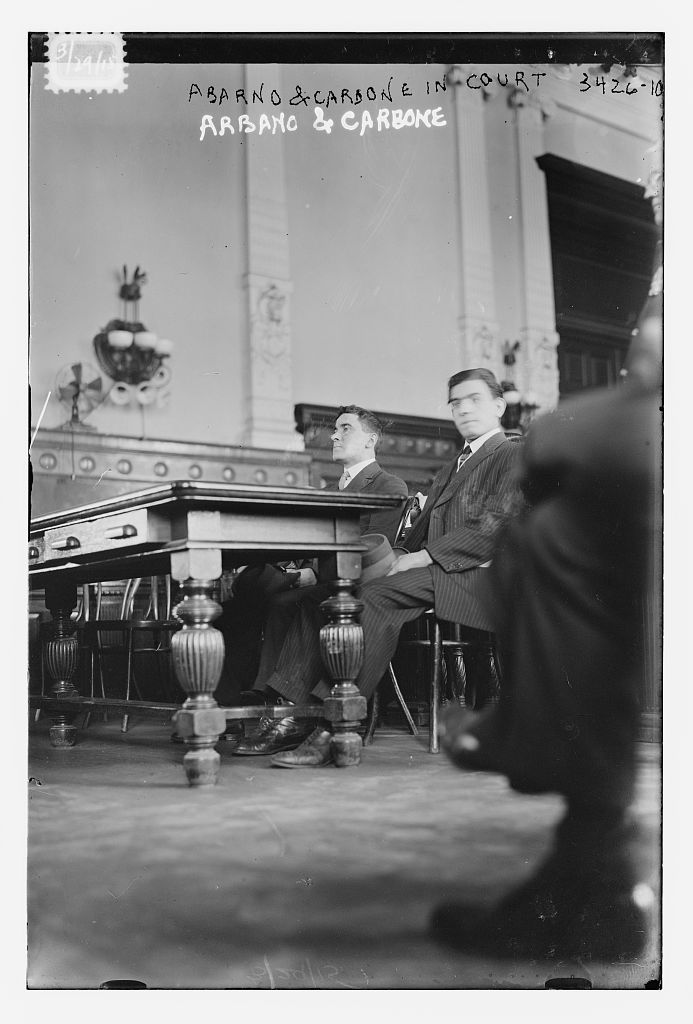

Abarno and Carbone both eventually broke down and were promptly convicted. They were both sent to Sing Sing in April where they both served six year terms.

Newspapers the following day declared “the episode was the culmination of one of the most intricate pieces of detective work ever achieved by the New York police.”

However the bombings would continue. The most dramatic incident would take place on September 16, 1920, with a bomb detonating on Wall Street, killing 30 people.

Forms part of: George Grantham Bain Collection (Library of Congress).

1 reply on “Terror on Sunday: The failed plot to blow up St. Patrick’s Cathedral”

My ex husband was Benjamin Carbone and his father was Geronimo Carbone were they related to Carbone