Everybody sees Coney Island a little differently. Most people know it for the amusements but not everybody has the same feeling about them. One person craves the beaches, the food. Another prefers a stroll along the boardwalk, fireworks, an evening Cyclones game. Others live nearby, too familiar with the swelling weekend crowds. And some people — and this seems like blasphemy — have had their fill of Nathan’s hot dogs.

Coney Island has always been a Rorschach test of class, morals and taste, an escape from the city for more than 150 years. (In the 19th century, it was an escape from two cities, as Brooklyn was independent then and had not yet subsumed Coney Island within its borders.)

Coney Island has always been a Rorschach test of class, morals and taste, an escape from the city for more than 150 years. (In the 19th century, it was an escape from two cities, as Brooklyn was independent then and had not yet subsumed Coney Island within its borders.)

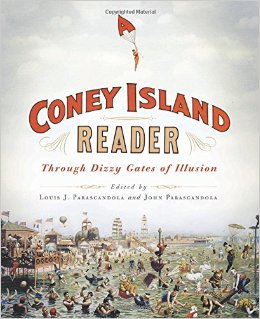

It’s never been considered a bastion high culture, although its degrees of middle- and low-brow have been vibrantly written about from the very beginning. Â In The Coney Island Reader: Through The Dizzy Gates of Illusion, edited by Louis J. and John Parascandola, we get a time machine through its many iterations, thanks to the observations of dozens of writers.

I don’t think of Coney Island as a particularly literary destination, and yet here we have some of their greats chiming in to describe the lusty pleasures of Brooklyn’s beach-side getaway.

We begin with Brooklyn’s greatest voices — Walt Whitman. “Yes: there was a clam-bake — and, of all the places in the world, a clam-bake at Coney-Island! Could moral ambition go higher, or mortal wishes go deeper?” Â He’s writing in 1847 when the area is a barely developed destination.

Jose Marti, the poet and Cuban revolutionary, is overtaken by its magic. “And this squandering, this uproar, these crowds, this astonishing swarm of people, lasts from June to October, from morning until late night, without pause without any change whatsoever.”

Today’s Coney Island amusement district is vastly smaller than the one which greeted Stephen Crane in 1894. Â “We strolled the music hall district, where the sky lines of the rows of buildings are wondrously near to each other, and the crowded little thoroughfares resemble the eternal ‘Street Scene in Cairo’.”

As Coney Island grew larger in the early 20th century — with its three principal amusement parks Dreamland, Steeplechase and Luna Park — it pulled thousands more to its whimsical attractions.  It’s almost  hilarious to picture Russian writer and dramatist Maxim Gorky sitting inside the Dreamland ride Hellgate, with its hellish flames “constructed of paper mache and painted dark red. Everything in it is on fire — paper fire — and it is filled with the thick, dirty odor of grease. Hell is badly done.”

The Coney Island Reader combines literary observances with social commentary and documentary accounts featuring interviews with the impresarios themselves.  In a 1909 magazine article by Reginald Wright Kauffman, George C. Tilyou, the owner of Steeplechase Park, proclaims, “To sum up my opinion of the whole thing, we Americans want either to be thrilled or amused, and we are ready to pay well for either sensation.” (George’s brother Edward is represented here with a vivid essay called “Human Nature with the Brakes Off — Or: Why the Schoolma’am Walked Into the Sea.”)

More contemporary observations of the fictional kind are represented by Kevin Baker (who also contributes the forward), Josephine W. Johnson and Sol Yurick (from the novel which inspired the film The Warriors).

This is perhaps the only book in history that features the writing of e.e. cummings and Robert Moses. One saw saw “[t]he incredible temple of pity and terror, Â mirth and amazement,” the other “overcrowding at the public beach, inadequete play areas and lack of parking space.”

Ah, Coney Island. It’s what you make of it.

The Coney Island Reader

Through Dizzy Gates of Illusion

edited by Louis J. Parascandola and John Parascandola

Columbia University Press

Top image: Luna Park at night, 1905 (polished up image courtesy Shorpy)

1 reply on “The literary Coney Island”

Did you ever see Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s book of poems, “A Coney Island of the Mind”? Though none of the poems specifically reference CI, they do evoke the beauty, gaudiness and grotesquery of the place. One example is called, ironically, “The World Is a Beautiful Place.”

Also, on the cover of the original printing of the book is the photograph of Crystal Palace you have on this website.