The celebration of April Fools Day traces back to the Middle Ages and possibly as far back as the Roman era. In the mid-19th century, the unofficial holiday for pranks provided a good excuse to attack political opponents.  Here are a couple samples of writing from New York publications from this period which I’m quoting at length because I’m a fan of the almighty air of jadedness that pervades these articles. Also — use of the words “operose” and “gew-gaws”:

From the New York Times, April 2, 1861:

“There is a time for all things, we are told. Every dog will have his day, and all fools must have theirs. All fools; and which are the wise ones? Let him among us who is most perfect in wisdom, play the first prank.

And the 1st of April in each year, is the day of all others by common usage consecrated to folly. If there are more senseless acts committed within its twenty-four hours than on any other single day of the three hundred and sixty-five, it has a record not much better than JAMES BUCHANAN’s.*

It is the anniversary on which half-witted people endeavor to make others appear to be so; and they labor to draw forth an ill-advised word or act from them much upon the principle that gave birth to the adage, “Set a thief to catch a thief.”

The custom of late years, it would seem, like an irreverent Dutchman, has more of breaches than observance. Little children honor it, and always will honor it, and may be excused for honoring it; but they who are at years of discretion should put away childish things.

We detest April Fool’s Day. We do not believe in it, and have not believed in it since — yesterday.

To be frank, the writer of this, in the pursuit of pabulum, yesterday, was “sold,” fooled, taken in, deluded, deceived, swindled at every step. He was sent on “Fool’s errands” to distant parts of the City by hypocritical friends whom he told to their double faces afterwards, when they taunted him, that if he had been on “Fool’s errands” it was their errands that he had gone to perform.

Then shameless little urchins threw tempting parcels in his path, and when he stooped to pick them up, behold! they were up before he could pick them, dangling high in air, pendant by cords from windows, from which deriding faces looked down upon him. And his pockets were turned inside out, and placards were hung on his back, or suspended from his coat-tails, and when, losing his way, he civily asked the name of a street. — “No you don’t,” was the answer. “April fool!”

And so, after a day spent in anxious but unrequited efforts to get leisure to write of it, he sat down late, and weary, and concluded to take revenge upon the reader, and say to him simply, “April Fool!””

* In 1861 James Buchanan was at the end of his presidency. He was also a Democrat and thus unfavored by the Republican-leaning New York Times of the mid-19th century.

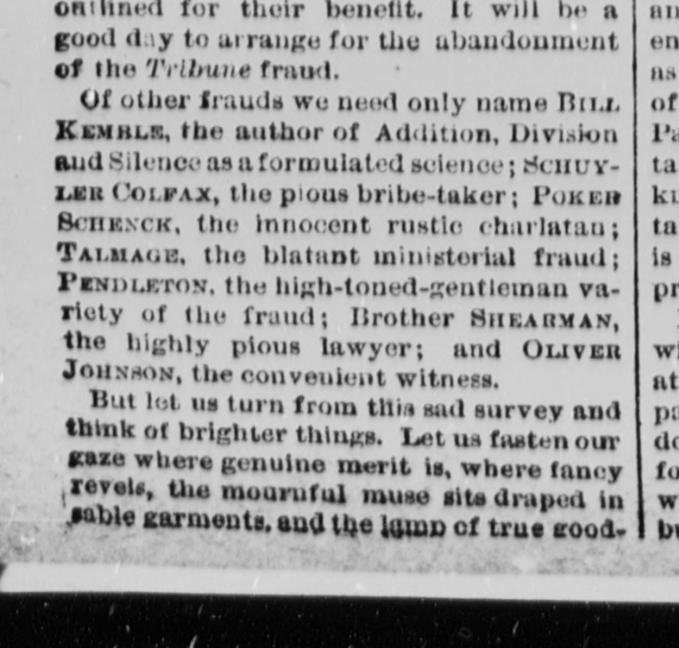

Other newspapers used the holiday as cover to rail against political opponents. Â Â On April 1, 1876, the New York Sun ran down a list of so-called April Fools, calling out some of the biggest names in politics. An excerpt:

“We cannot better celebrate this day dedicated to fools and folly, than by considering some of the principal frauds, humbugs, charlatans, hypocrites and fools who infest the country, and dwelling for a moment on their history and prospects.

They are a large and thoroughly self-satisfied company, recruited from various ranks of society and armed with impudence, pretension, cant or simple stupidity. They like to be observed and entertain a low opinion of those who criticize them.  They think they out to be permitted to practice their trade unmolested by impertinent scrutinizers of their shoddy materials, short weights and other tricks of deception.

Today let us celebrate the glories of their enterprising company, carefully abstaining from any word or suggestion to which they can fairly take exception.”

Among their list of the greatest fools in 1876:

“Ulysses S Grant**Â — “cannot strictly be called a fraud. His practice of greed is open, and he believes in it. Â Once of the very lowest estate, a social wreck and failure, he was lifted by a bloody war to the high ground of eminent position where all men could see him. Â If ever a man had reason to be thankful for the happy fortune which enabled him to get out of the mire and to stand in clean places, it’s Grant.

Hamilton Fish — “is a pompous sailor, replete with the airs of an operose and ostentatious respectability …. and in fact, Fish is one of the hollowest of frauds.

Henry Ward Beecher*** — “the cheekiest fraud,” “old and unblushing in licentiousness, he takes the part of a manly fellow and a holy man, and with variations of buffoonery, plays it to the entire satisfaction of the brethren. Â But paint and gew-gaws cannot cannot hide the foulness underneath. Â His reputation is gone, and he lives on lies and perjuries.

Jay Gould — “is a great fraud, but he was a fool in buying the [New York]Tribune, hiring the young editor as a stool pigeon, and building the tall tower.****

There there’s this whole paragraph:

**He was at the end of a scandal-ridden presidency, and his cabinet was known for a bevy of corruption charges.

***His adultery trial had sullied his reputation the previous year.Â

****Gould, his connections with Tammany Hall well publicized, had bought the Tribune, a rival to the New York Times, in the years before he began amassing railroad property.

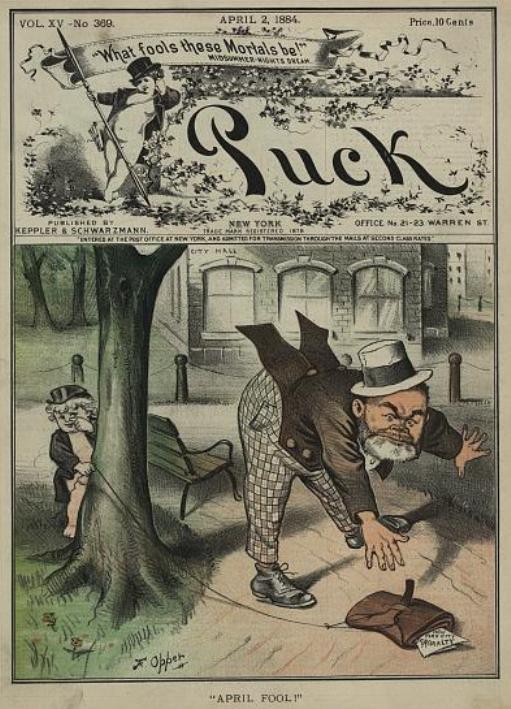

Puck Magazine courtesy the Library of Congress

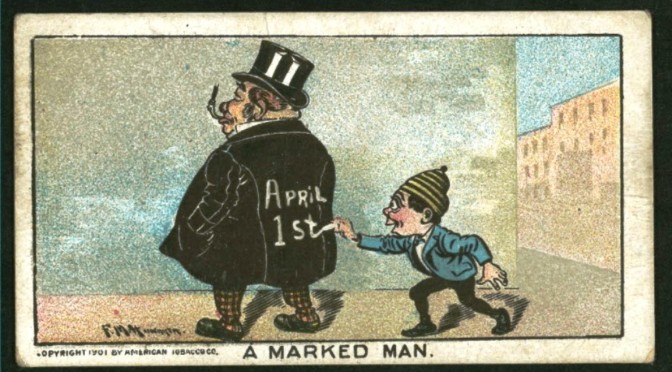

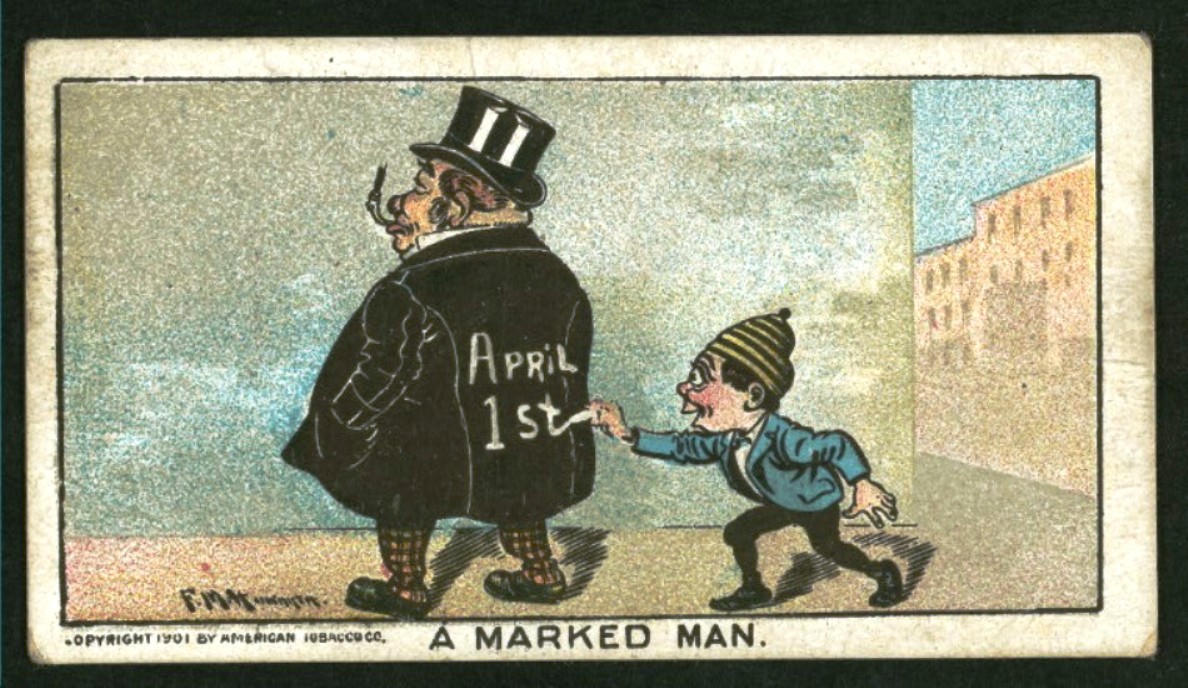

A Marked Man illustration courtesy New York Public Library