An airplane crashing into Central Park? Believe it or not, in the early days of flight, these sorts of stories were somewhat frequent, although in this case, the pilot and passenger got out okay.

Quote from newspaper coverage. From the New York Evening World, March 6, 1916:

“Alexander H. Thaw, the millionaire aviator, and John Kane, his mechanician, dropped 4,000 feet with a hydroaeroplane into a tree in Central Park this morning. Â The machine was almost a total wreck but both aviators slid to the ground with hardly a scratch. Â Thousands who had witnessed the flying machine drop from its dizzy height rushed into the park expecting to find the two flyers crushed to death.”

The New York Times puts the plane even higher in the sky!

“While circling the heavens, hoping to get some glimpse of Governors Island, the gasoline in the biplane’s tank gave out and the engine stopped. Â The youthful aviator did not lose his head, however, but started volplaning to the earth in long spirals, both he and Kane on the lookout for a safe landing place.

Soon they were about to pick out Central Park, and Thaw guided the biplane to the sheepfold, where it is likely he would have landed without mishap had not the left wing of his machine caught in a tree. The car tipped then, but neither occupant was thrown out, and the biplane came to rest on the earth, with both wings badly broken, the tipping having broken the right one against the earth.”Â

The airplane crash would have startled not just Central Park’s human patrons, but the actual sheep of Sheep Meadow (pictured below in 1910, picture courtesy Museum of the City of New York)

From the Evening World:

“Thaw and Kane found they had no broken bones and when they were surrounded by the crowds that had watched their fall they were ruefully gazing aloft at their broken bird.

‘Well it might have been worse,’ remarked the young aviator and then he set to work to have the hydroaeroplane taken out of the tree and shipped back to Garden City [to Roosevelt Field on Long Island].”

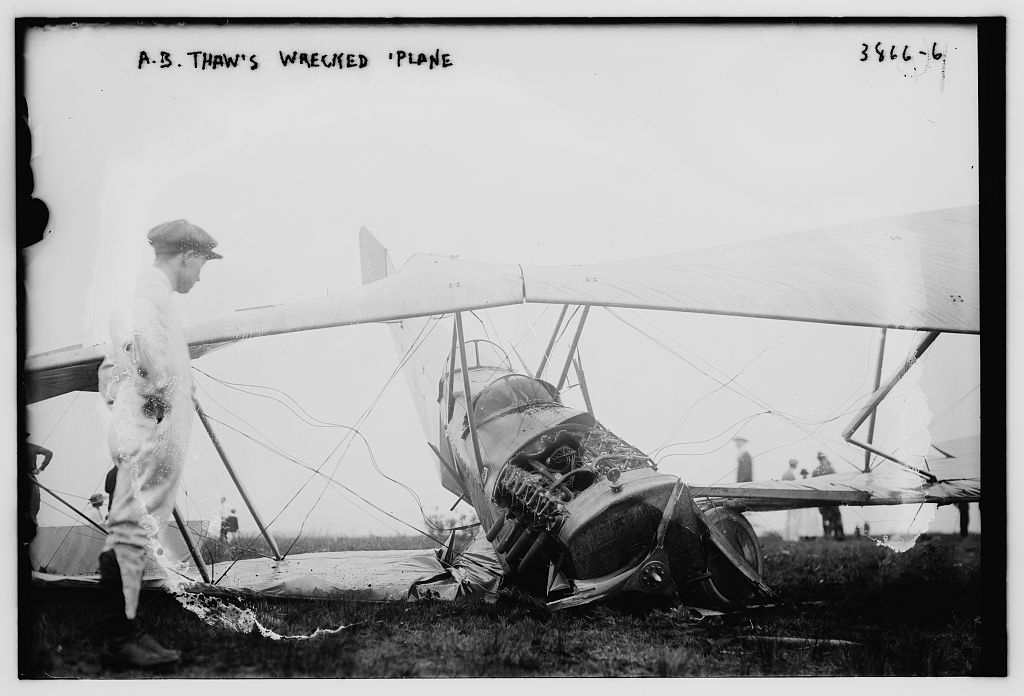

A photograph (from the Library of Congress) of the dramatic aftermath:

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Thaw would distinguish himself as one of America’s boldest and bravest young flyers, entering into America’s inaugural aviation service during World War I. Tragically he was killed in France on August 22, 1918, when his plane experienced engine failure. He was not as lucky then as he was on that day in Central Park. Â “The engine trouble developed at an altitude of 2,000 feet and the machine when it fell struck a number of telephone wires and collapsed, upside down.” [source]

His brother William Thaw was also a pilot and became renown during World War I. He’s generally considered to be the very first American aviator to engage in battle during the conflict. Thaw survived the war and died in 1934 a decorated hero.

And if you’re wondering about that last name Thaw. Yes, indeed the murderer of Stanford White — Harry K. Thaw — is indeed from the same family.