Looking for an easy gift idea this holiday season? Our book The Bowery Boys Adventures In Old New York would make a pretty amazing present for the holidays. Give it to loved ones who like history or New York City or to those who simply enjoy books with lots and lots of old pictures. (We lost count at some point of the number of pictures. Well over 400 at least.)

Here are a few short excerpts from the book pointing out a few holiday themed moments in New York City history. Â You can buy the book at Amazon, Barnes and Noble or at your local bookstore. (In New York, among many throughout the city, you can try the Strand, McNally Jackson Books and Three Lives & Company — where we went in and signed a few!)

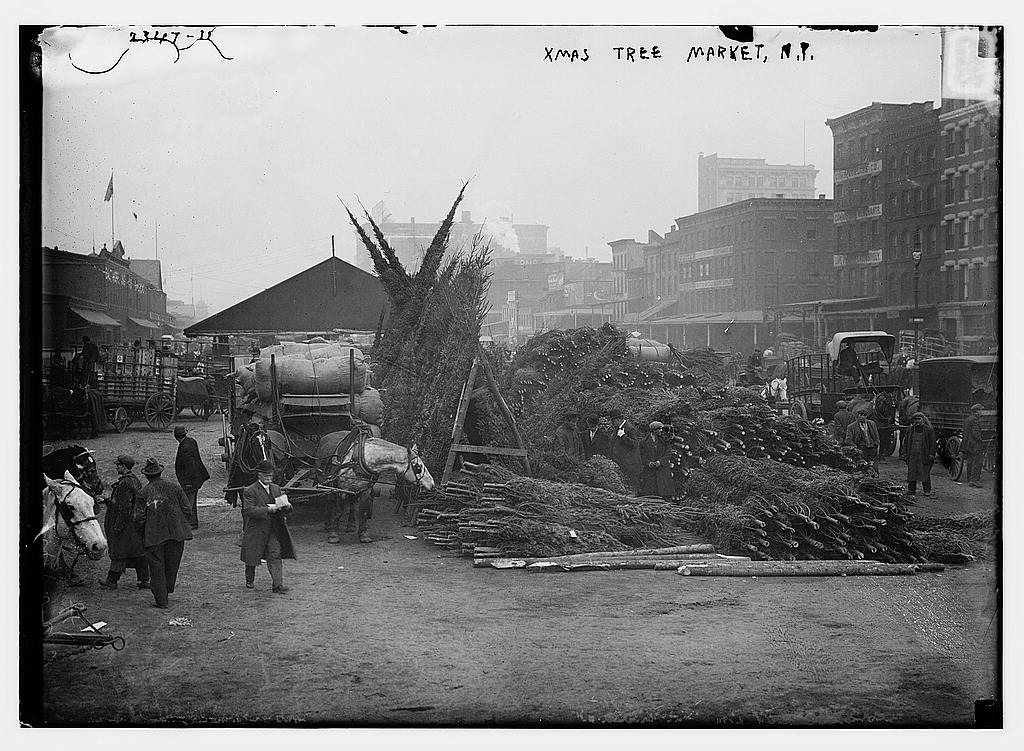

The First Christmas Tree Stand

Today’s cute little Washington Market Park sits on the spot of New York’s most important outdoor market of the nineteenth century. In the days before mass refrigeration and chain grocery stores, Washington Market was the place where New Yorkers came to buy their meats and fresh produce.

First opened in 1812, the market offered many residents their first encounter with exotic food items from across the country and around the world. (Today a Whole Foods one block away provides much the same function, albeit with higher prices and gluten-free options.)

But this market wasn’t just for edibles. In 1851 a woodsman named Mark Carr, living in the Catskill Mountains, chopped down a selection of fir and spruce trees, shoved them into two ox sleds, carted them over to Manhattan on a ferry, and set up shop in the market, paying one dollar for the privilege of selling his rather prickly merchandise.

Holiday revelers were thrilled to be spared the journey out of town, and Carr’s entire stock of evergreens sold out within the day. No surprise then that other farmers jumped on this evergreen opportunity, and within a few years the open-air Christmas tree market was born. (Chambers and Greenwich Streets)

A Present for the Lower East Side

“Little Flower†was the nickname of Fiorello La Guardia, New York’s short but forceful mayor, who during his tenure (1934–1945) introduced many vital housing reforms. The sprawling thirteen-building housing development known as LaGuardia Houses was completed in 1957, ten years after his death. A bust of La Guardia sits in the adjoining park—Little Flower Playground.

But the treasure here is the extraordinary relic located next to it. This is the former public bathhouse, called the Whitehouse, which opened on December 23, 1909, and was one of thirteen public bath facilities in New York.

It was built for the poor residents of Corlears Hook who lacked adequate water facilities, a function reminiscent of the ancient bathhouses of Rome. By the 1940s indoor plumbing had rendered the public bath obsolete, and so it was converted into a public swimming pool and gymnasium. Today it sits unused, a ruin from another time. (Madison Street between Clinton and Rutgers Streets)

Clement’s GiftÂ

As the story goes, on Christmas Eve in 1822, Clement Clarke Moore completed a seasonal poem to read to his young children. He penned the whimsical little tale—a throwaway, really, in comparison with his great and respected academic writings on Greek and biblical literature—from a desk at his comfortable, snow-covered mansion, which the family called Chelsea.

The home sat atop an old hill (near today’s modern addresses of 422–424 West 23rd Street), which looked out over Moore’s vast estate, stretching to the south from here.

According to legend, Moore had been inspired that day during an outing to Washington Market to purchase a Christmas turkey.

The poem, “A Visit from St. Nicholas†and often referred to as “’Twas the Night Before Christmas,†would eventually help shape the story of Santa Claus. His verses practically spelled out the jovial North Pole gift-giver’s physical appearance, which was then illustrated by New York–based newspaper and magazine illustrators like Thomas Nast and, in the twentieth century, the Coca- Cola advertising of Haddon Sundblom. Moore even named all eight reindeer.

Moore’s poem was published anonymously the following year, and he’d only take credit for penning it—at his children’s insistence—in 1844.