The subtitle to Kay S. Hymowitz‘s engaging and often provocative new book The New Brooklyn: What It Takes To Bring A City Back is a bit of a misnomer.

Brooklyn is not back in any conventional sense of the word. It has not returned to any kind of sense of normalcy or financial stability. In fact, Brooklyn has never felt more granular, a borough with newly formed and slightly unstable multiple personalities. If it were a person, you might medicate it.

Brooklyn is back — for many, safe, vibrant and livable —Â but it is also beyond. It’s in a category all to its own.

Below: The new Williamsburg

Brooklyn is also my home. I live two blocks from a row of millionaires to the east and two blocks from working class residents in a housing project to the west. Retail options are frayed and deeply unsatisfying to all — expensive boutiques next to drug stores with lines down the block. No grocery stores in sight. A few blocks away lies the Gowanus Canal, a perilously grim body of water that now, in 2017, attracts glassy chemical films on its surface and luxury condos at its banks.

The past two decades in Brooklyn have been transformative in a way that few places in the world have experienced. This is certainly the most tumultuous era for the borough since it was dragged into the embrace of Greater New York — via the Consolidation of 1898.Â

It can be one of the greatest places to live in the United States. It can also be a frustrating, hopeless place. Its dysfunctions are legion. The pockets of Brooklyn which foster great cultural changes are never far from others that are (intentionally or otherwise) closed to any sort of change.

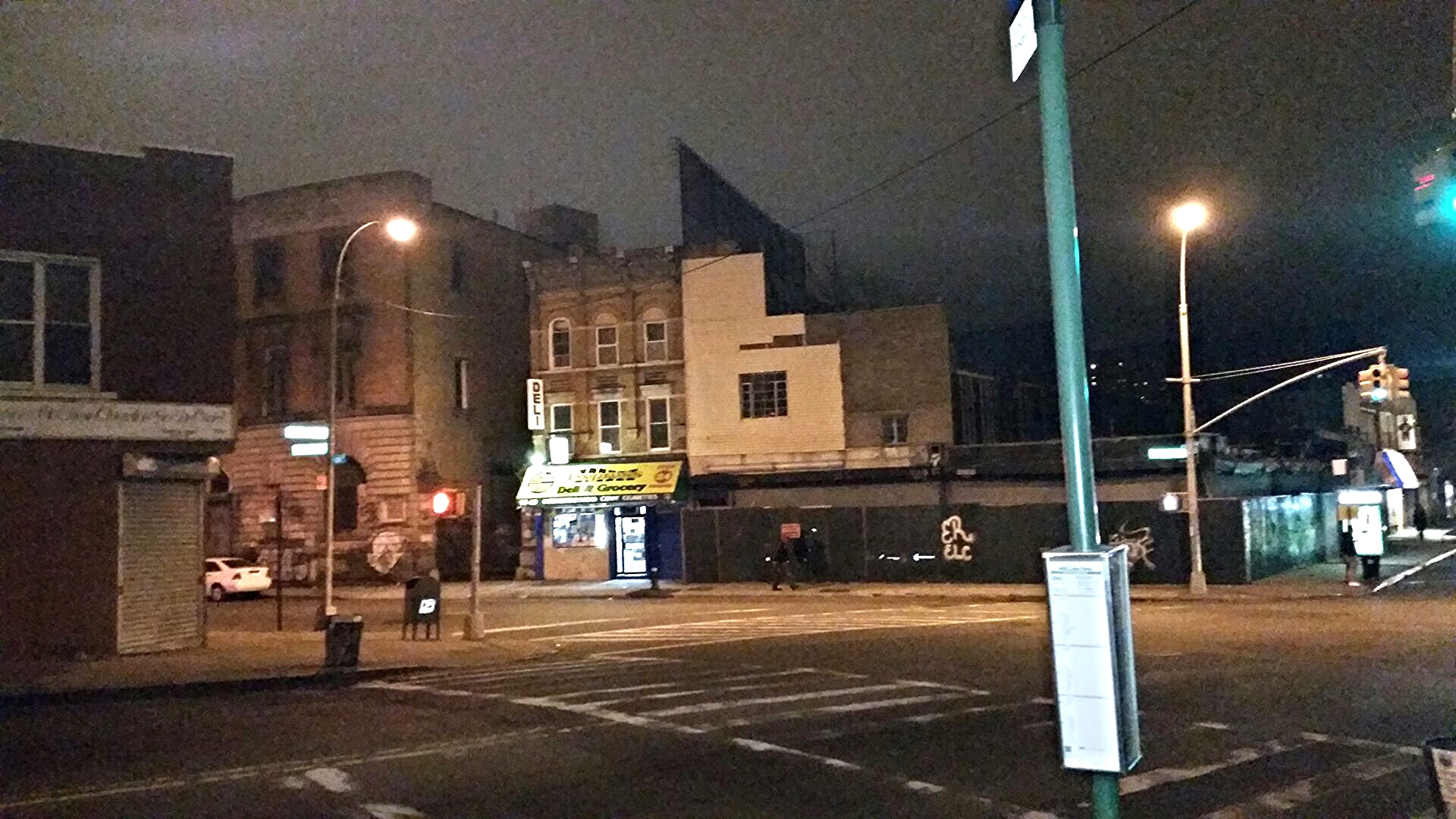

Below: Sunset Park

Recent shifts began in the early 1990s when younger people, mostly single, began flocking to the industrial neighborhood of Williamsburg after they couldn’t find acceptable space across the river in the East Village and the Lower East Side. This, in itself, was not a new phenomenon; Brooklyn Heights saw a similar ‘bohemian’ gentrification a century ago, as did Park Slope in the 1960s and 70s.

But the Williamsburg migration initiated a widespread lurch of gentrification into Brooklyn — some of it, as Hymowitz notes, with great degrees of population displacement. Gentrification is considered a bad word for many, a sign of Brooklyn becoming deeply homogenized to the detriment of its working-class residents.

The New Brooklyn

What It Takes To Bring A City Back

by Kay S. Hymowitz

Roman & Littlefield

In The New Brooklyn, Hymowitz looks at the more nuanced effects of gentrification by diving into the histories of seven neighborhoods — Park Slope, Williamsburg, the Brooklyn Navy Yard, Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brownsville, Sunset Park and Canarsie. (My only objection to this book is that the surveys are so engaging that I would have loved to read her take on other intriguing corners — Red Hook and Brighton Beach, for example.)

Below: Brownsville

She notes that gentrification, even of the most well-intentioned kind, is always fated for a rough landing. “When the educated middle class sets up housekeeping amid people from a different culture — whether white working class, poor black or immigrant  Hispanic, Chinese or whoever — tensions are inevitable.”

Gentrification in Brooklyn has come in all forms, with varying degrees of displacement. While sensitive liberal tenancies among current displacers has made gentrification into a bad word, this was not so deeply concerning in the 1960s — in Park Slope, for example — when the city was spiraling towards financial doldrum.  Writes Hymowitz:

“[G]entrification can drive out residents by increasing evictions, demolitions and landlord harassment, and raising rents to heights that existing tenants cannot afford. This kind of displacement has a decades-long history in gentrifying Park Slope. In the early days (and despite their countercultural sympathies), brownstoners made no bones about wanting to evict tenants whom they often inherited with their newly purchased brownstones.”

Below: Park Slope

Yet the Williamsburg-into-Bushwick-and-beyond form of gentrification is of an entirely different breed; it became an international model for urban renewal. “Everyone, including people who might have once aspired to the Ritz, whether in Tokyo, Stockholm, Berlin, Philadelphia or Chicago, wants to be cool in a Brooklyn sort of way.”

While this has made Brooklyn an overall safer place to live, it’s also created an experience quite out of reach for many. In Hymowitz’s survey, she also visits Brownsville, a neighborhood almost entirely closed off from the so-called “rebirth,” a place where residents, mostly poor and working class African-Americans, are struggling to break free from life in “the permanent ghetto.”

The New Brooklyn is anchored firmly in history with an excellent overview of Brooklyn’s past upfront and startling neighborhood histories beginning each chapter. History explains the reactions to modern changes.

In Bed-Stuy, longtime residents are concerned that rapid gentrification is changing the nature of this historic center of black culture. While in Sunset Park, as Hymowitz notes, “you’d be hard-pressed to find any anti-gentrification protests or activists taking up the cause.”

— By Greg Young

Below: Bedford-Stuyvesant

Top picture — Brooklyn 1945, courtesy New York Public Library