BOOK REVIEW The history of sports is often written around its most revered role models, as though the noble character of the greatest players comes from the purest devotion to their game.

Leo Durocher, a sterling shortstop and manager for some of the greatest teams in baseball history, was no role model. In most ways, he was the very opposite, a combative player with a rock-star personality. He’s famously attributed as saying “Nice guys finish last,” not because he actually said it, but because it seemed to be his life’s slogan.

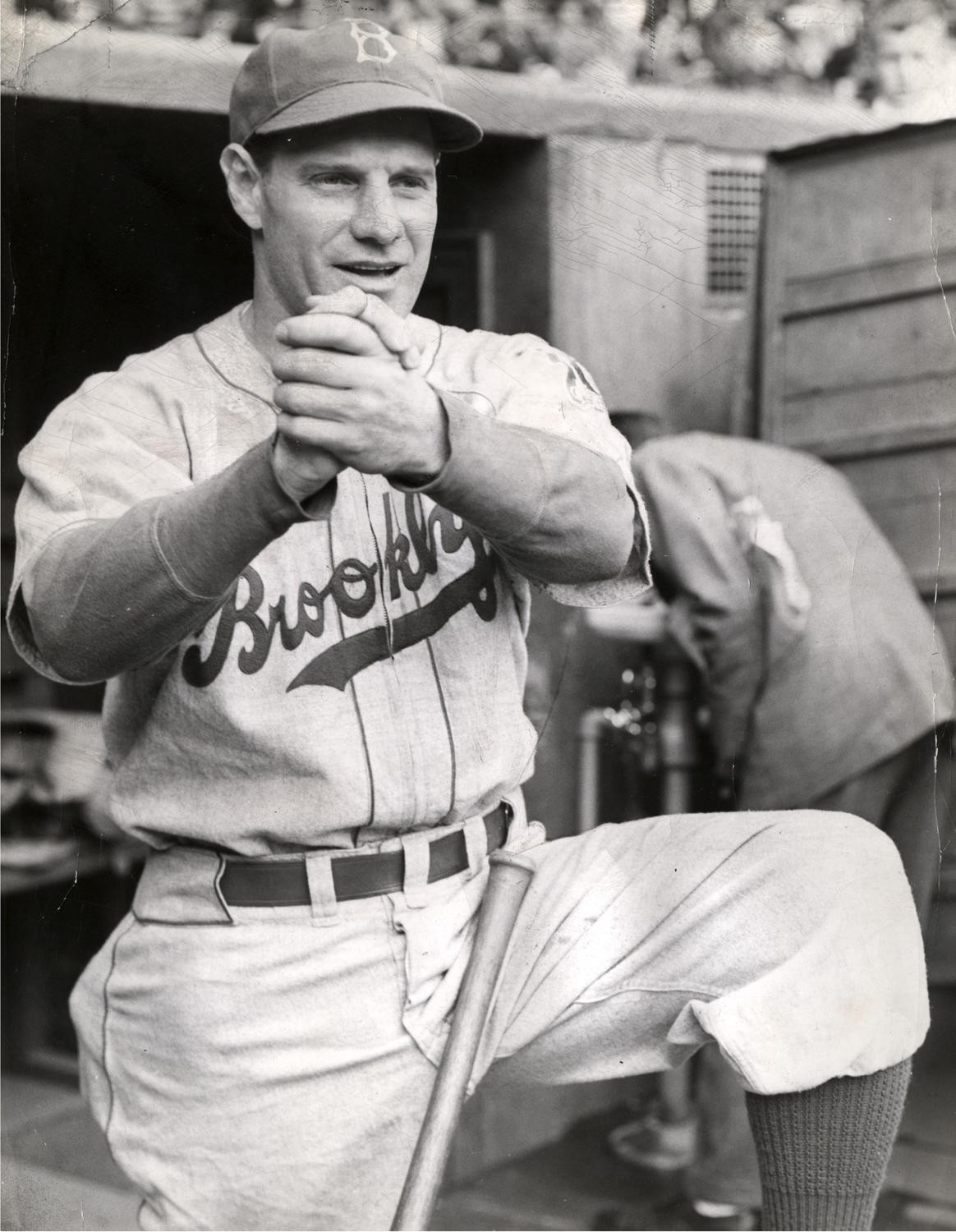

In Paul Dickson‘s fast-paced and often amusing biography, Durocher’s extraordinary accomplishments on the field battle for prominence with the player’s indulgent and never-ending quest for the good life. Along the way, he became an iconic New York sports hero. As a player for the New York Yankees (1925, 1928-29), the Brooklyn Dodgers (1938-48) AND the New York Giants (1948-1955), his story plays out in New York’s greatest ballparks, as well as its most glamorous nightclubs and hotels.

Leo Durocher: Baseball’s Prodigal Son

by Paul Dickson

Bloomsbury Publishing

Durocher, born in Massachusetts to French Canadian parents, has had many nicknames through his career — Frenchy, “the All-American Out,” and a great number of four-letter ones. But “Leo the Lip” seemed to fit him best. His quarrels with other players, umpires and sportswriters are the stuff of legends.

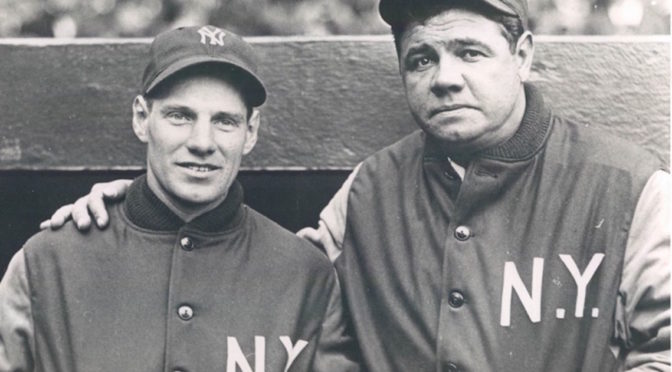

Babe Ruth famously couldn’t stand him. At one point, he accused Durocher of stealing his watch, an alleged theft that would follow the players from the Yankees to the Dodgers. Writes Dickson: “As Leo said, in a half-angry, half-mocking tone, ‘Jesus Christ, if I was going to steal anything from him I’d steal his god-damned Packard.”

His expletive-filled spats with teammates and managers tarred him early in his career; at one point, at age 24, Durocher was considered ‘washed out’, a toxic presence distracted by decadence and fame. As Dickson writes, “One rumored reason that all the teams in the American League passed on Durocher was that Babe Ruth let it be known he wanted Durocher out of the league.”

In New York, Durocher hops from the Cotton Club to the Stork Club in fancy suits, racking up debts at trendy hotels and acquiring a coterie of suspicious characters. His gambling addiction is now legendary; although many baseball players squandered their salaries this way, Durocher seemed to treat gambling as a second sport.

This led him into the circles of both mobsters and movie stars. And there, in the middle, was Durocher’s close friend George Raft, the Hollywood actor who frequently played gangsters on film. Durocher emulated Raft — often dressing and parting his hair in similar ways –Â and the actor, in turn, introduced the baseball player to the thrills of the entertainment world.

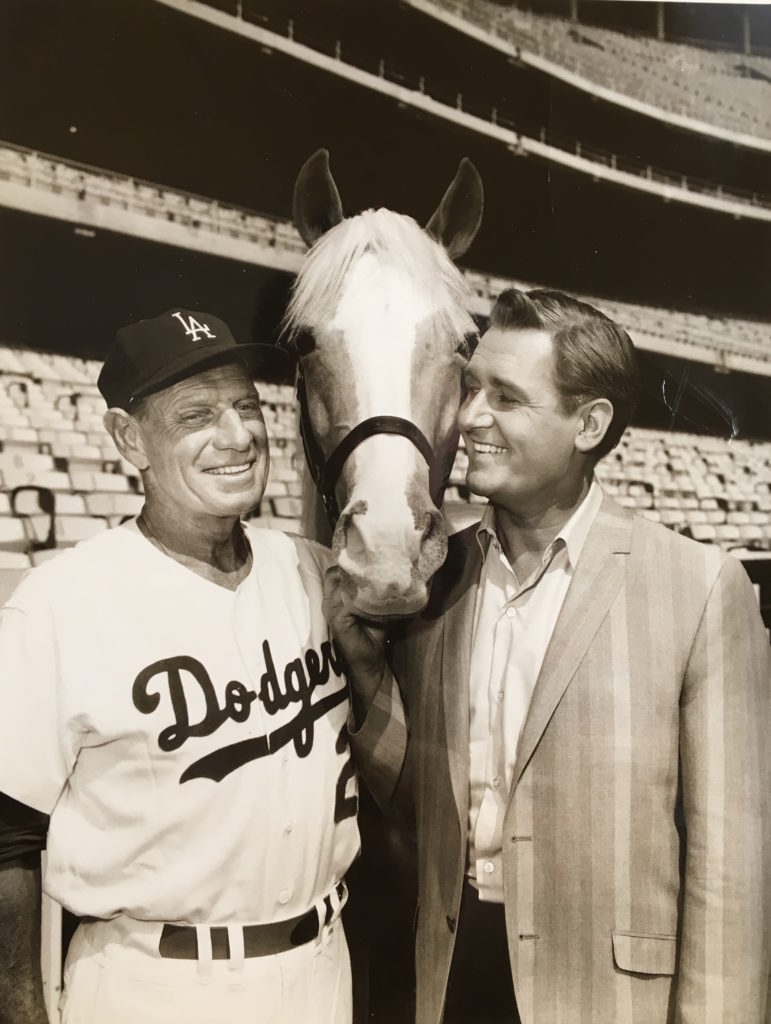

Below: Durocher with the stars of the TV show Mr. Ed

Even during his greatest moments as a manager of the Dodgers, many believed Durocher might quit and become a radio comedian and actor. During World War II he even toured with the USO.

Yet he would always return to the game. With the Dodgers, he transitioned from player to manager, overseeing the team during some of its greatest moments. That included the years with Jackie Robinson, the first African-American player. (Of course, Robinson and Durocher would later public feud, almost a rite of passage for great baseball stars at this point.)

Dickson, a long-time chronicler of baseball history, finds a readable balance between Durocher’s on-field achievements and late-night scandals, revealing a charming and exceptionally scrappy, if not exactly likable, sportsman.

He’s harsh and mouthy to the end. But his talent was undeniable; the writer Bob Broeg, at Durocher’s death in 1991, said that “losing Leo Durocher was like losing either an old friend or an old enemy — you could take your pick.” Over the years, the writer had gotten into several fist-fights with Durocher.