You may know Nathan Hale well from history books or from New York’s numerous memorials as a symbol of American patriotism, dying for his country long before anybody actually thought it would ever be a country.

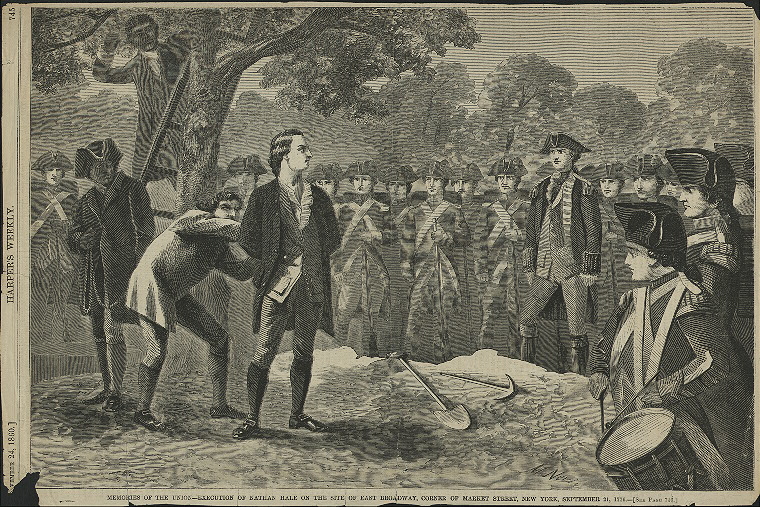

The British hanged him in New York as a spy in the aftermath of the Great Fire of 1776. He had performed no great deed for George Washington and his army — his intel never made it back to the general — except for volunteering for the spy mission in the first place.  His gift to the future United States was in believing it would exist.

But what if things had been a little different in the life of Mr. Hale as a young man? What if, Sliding Doors-style, decisions made by him and his loved ones had sent him down a different path? What if his ardent patriotism had, instead, been in support of the British cause?

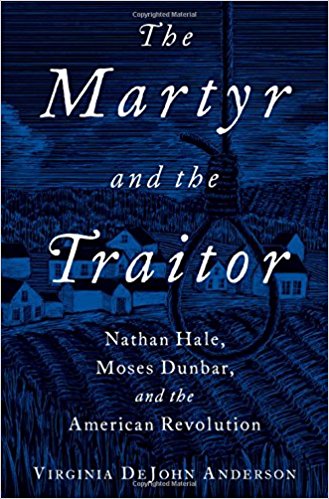

In a captivating new book by Virginia DeJohn Anderson, a professor of history at the University of Colorado in Boulder, we are presented with an actual historical example — a contrasting figure nearly forgotten — to use for this thought experiment.

THE MARTYR AND THE TRAITOR

Nathan Hale, Moses Dunbar, and the American Revolution

by Virginia DeJohn Anderson

Oxford University Press

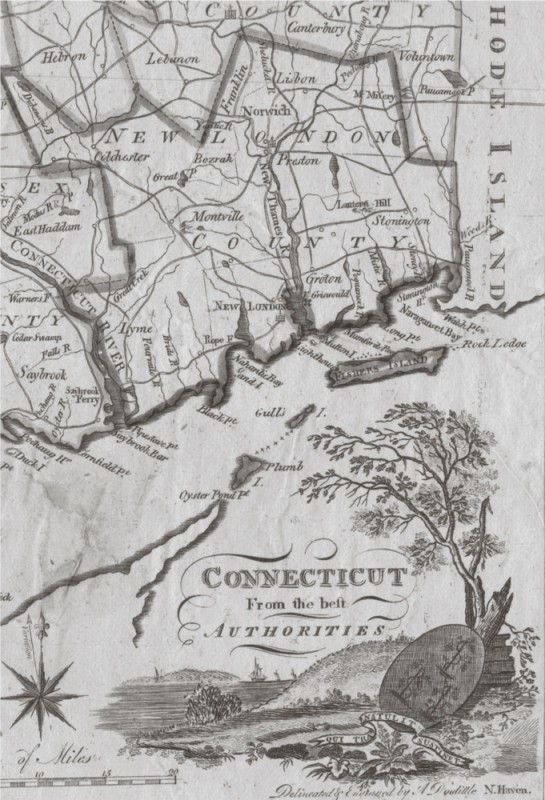

The story of Moses Dunbar is the flip-side to the Hale legend. The two Connecticut men were similar in a great many ways (although Dunbar was older) but circumstances led them to different causes.

Dunbar’s story is far less known than Hale’s of course. Hale was proclaimed a true patriot early in the Revolutionary conflict, and those with documents and information about the young schoolmaster proudly preserved them. His story is richly documented and well embroidered.

The opposite is true of Dunbar; he was hung in disgrace after returning home from a mission to recruit British sympathizers among his countrymen. It’s said that Dunbar’s own father offered to provide the rope.

Anderson tells both of their stories in parallel, and for a time, the reader can experience this book as an excellent social history of life in Connecticut in the mid 18th century — the degrees in which religion, marriage, education and land ownership play a defining role in an individual’s fate.

Dunbar became an Anglican, tied to the Church of England in a time with anti-British fervor was sweeping the countryside. In fact, there are moments when Dunbar seems far more radical than Hale (who, with his Yale education, is exposed to other feisty young men and books full of eye-opening revolutionary beliefs).

The most vivid portions of Anderson’s well-researched and excellently paced history involve violent attempts by anti-British mobs. Writes Anderson:

“As the weeks passed, Anglicans in general, not just clergy, became target of attacks if they did not announce their opposition to Britain. In East Haddam  a seventy-year-old Anglican parish clerk was yanked out of bed on a cold night, stripped, and beaten …… Rumors began circulating that Anglican clergy, in league with the detested Samuel Peters and with the approval of their congregations, were plotting to enslave the colony.”

Below: Nathan Hale’s schoolhouse in East Haddam, CT

Dunbar was radicalized by his environment and, observing such displays in his community, chose church (and, by extension, Great Britain) over country. His decision would destroy him and even lead his disgraced family into vigorously supporting the American cause.

In The Martyr and the Traitor, in putting Hale and Dunbar on equal footing, Anderson underscores the intensity of the moment and the uncertainty of its outcome. Hale’s patriotism seems all the more brave but so too does Dunbar’s intransigence.

Both men died on the noose away from loved ones; their ends embody the chaos and certain danger of the Revolutionary War.