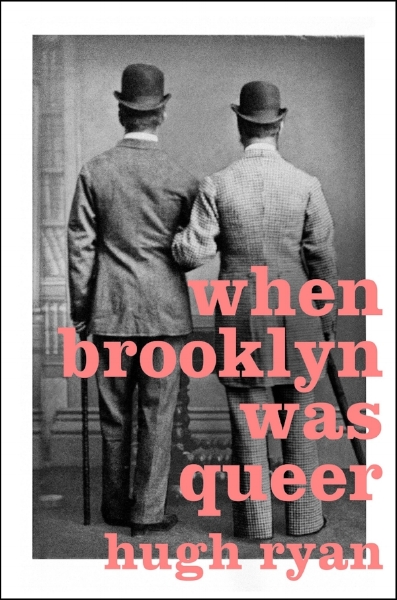

Hugh Ryan’s When Brooklyn Was Queer embarks on a modern quest to find the roots of the LGBTQ community in the pages of history.

A reader might hope to pick up Ryan’s book and find a reflection of their own world in the back alleys and parlors of Old New York — or rather, Old Brooklyn, the former city turned borough with its own genteel and sometimes stubborn personality. After all, many components of modern queer life were available and even thriving a century ago — homoeroticism, gender-swapping apparel, drag queens, cruising.

For a more in-depth look at the general history of downtown Brooklyn, listen to our podcast episode. And for a rundown of drag in New York, listen to this podcast episode: Absolutely Flawless.

When Brooklyn Was Queer: A History

Hugh Ryan

St. Martin’s Press

But the wondrous discovery of Hugh Ryan’s exceptionally well-researched book is that there really is no through line. The emotional or sexual desires might be similar, but the visibility of those we might label gay, lesbian and transgender today was either in performative contexts (vaudeville or sideshow entertainers) or ephemeral in nature (encounters in late-night saloons). The most celebrated individuals — the writers, artists and dancers — were often cloistered away in townhouse parlors.

Most of the connective tissue that might exist between these groups is undocumented. Like the ghostly voids of Pompeii, we see only the shadows of the lives they left behind.

Fortunately, Ryan provides those links in a rich and nuanced narrative, uniting the biographies of a group of extraordinary and often forgotten people.

But why Brooklyn? After all, Manhattan had the Greenwich Village coffeehouses, the Broadway shows, the Harlem drag balls, the most notorious speakeasies — all magnets for different aspects of historical LGBTQ life.

Ryan allows the transformation of Brooklyn from city to borough to parallel the shifts in modern thinking about gay and lesbian encounters.

Naturally, the story begins with Walt Whitman — born 200 years ago this year — whose story provides us with some of the earliest recollections of gay life in Brooklyn. For many gay writers, the legacy of Whitman was a literal beacon, drawing them to consider Brooklyn as a place to live and create. [For a deeper look into his life, listen to our podcast episode on Walt Whitman.]

Those readers hoping for anecdotes about a fabulous gay underworld in one of Brooklyn’s current centers of LGBTQ life — Williamsburg, Bushwick, Park Slope — will be disappointed. The bulk of Ryan’s stories are centered in the oldest areas of Brooklyn — Coney Island, Brooklyn Heights and the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

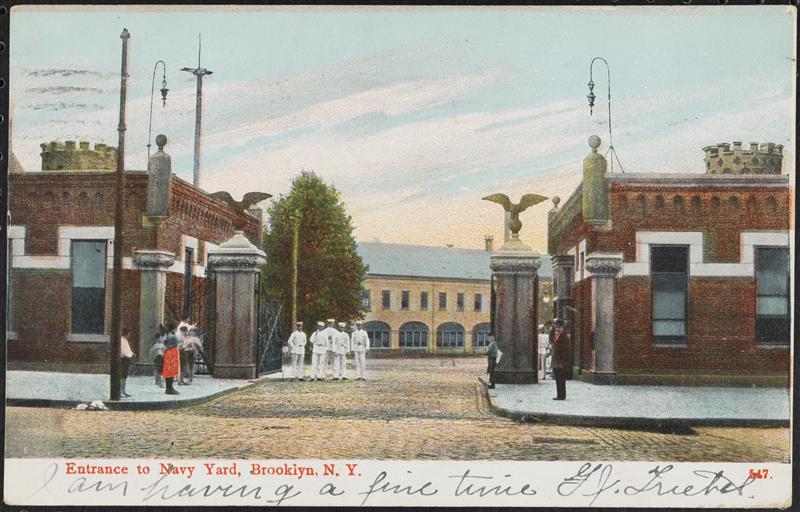

Brooklyn Navy Yard 1907 — Museum of the City of New York/ Ignatz Stern Communications

The Navy Yard! A magnet for tawdry saloons and horny sailors, the scene that centered around Sands Street resembles nothing we would recognize today because gay identity had yet to be fully established. “Properly gendered behavior … insulated men from being considered queer,” writes Ryan, “even if they were known to have sexual relations with men (or boys).”

Even by World War II, the streets surrounding the Navy Yard were well known for brothels catering to homosexual desires, most notably the wonderfully nicknamed Swastika Swishery.

One scintillating cabaret Tony’s Square Bar “was just ‘a couple of hundred yards’ from the Sands Street entrance to the Navy Yard and had a sign on the door that read NO MINORS UNDER 20 ALLOWED (in response to which one journalist wryly noted, ‘Minors age rapidly on Sands Street’).”

Meanwhile, increased employment opportunities for women during the war brought lesbians like Rusty Brown to the Navy Yard, a real-life Rosie the Riveterwho later became a professional drag king.

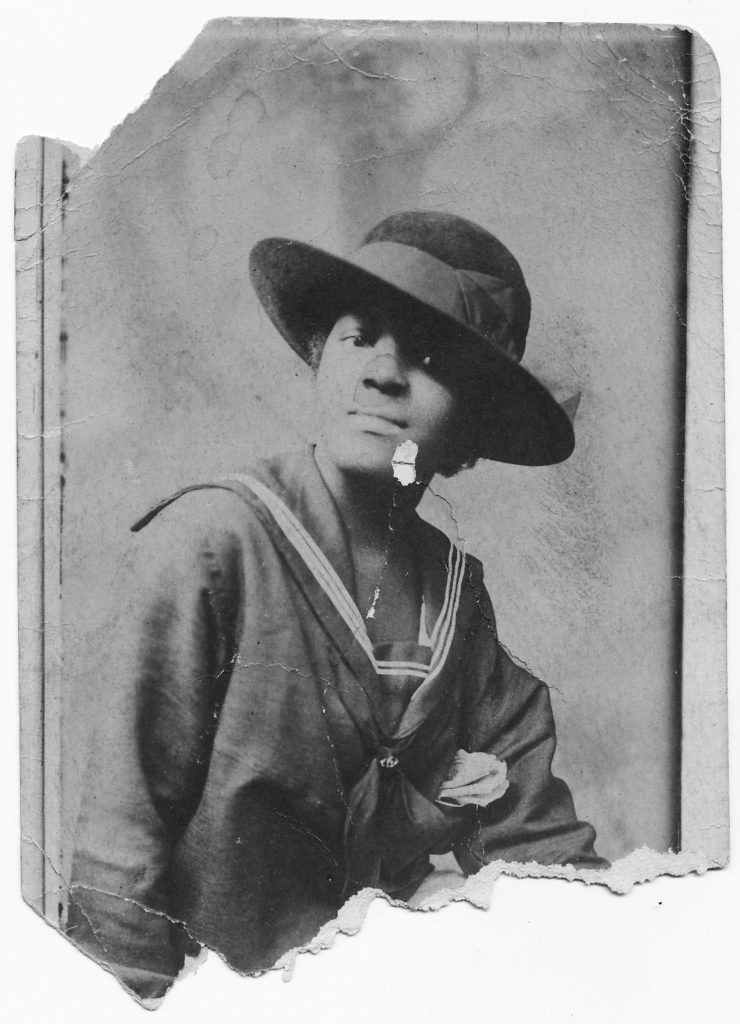

Before the 1940s, Coney Island offered the best opportunities for same-sex encounters and, in particular, the amusement district provides Ryan with the most appealing anecdotes of working-class Brooklynites and New Yorkers — from Loop-the-Loop, a trans sex worker named for a popular Coney Island ride, to Mabel Hampton (pictured above), an African-American dancer who had her first lesbian experiences here.

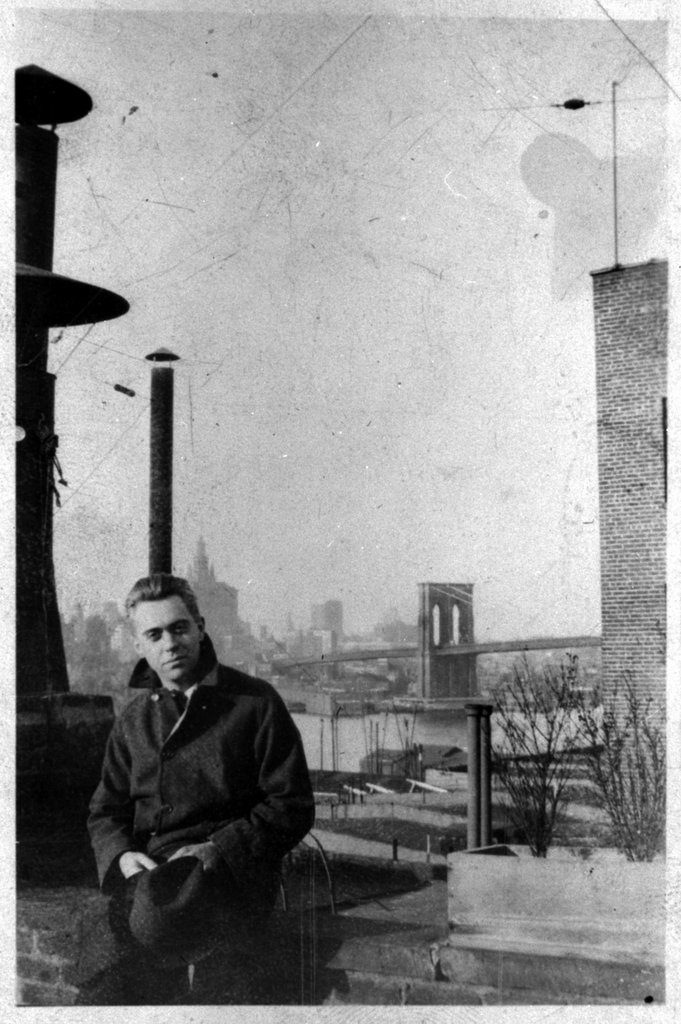

Another world emerges in the austere townhouses of Brooklyn Heights, the destination for artists and writers escaping Greenwich Village in the 1920s. The recollections of Hart Crane, Carson McCullers and W. H. Auden are some of the fullest descriptions we have of gay Brooklyn, albeit from the eyes of individuals who would become literary legends.

Ryan writes:

“In 1929, budding author Parker Tyler (who would write a scandalous gay novel entitled The Young and Evil just a few years later) encountered a campy gay waiter in a restaurant of Brooklyn Heights.

Tyler was so tickled by their interaction, and what he learned about the neighborhood, that he immediately wrote to friends to say, “Brooklyn is wide open and N.Y. should be notified of its existence.”

1 reply on “When Brooklyn Was Queer: The forgotten history of gay existence on the periphery of urban life”

Hello!

Can anyone identify the two women (pictured together), just below the page title? I am doing research on a photograph I purchased and would appreciate any information you may have concerning these two women!!

Best Regards,

P.Anderson