The 1896 landmark Supreme Court decision Plessy v. Ferguson embedded and legitimized the practice of “separate but equal” into American life in the 20th century.

The decision built racism into the fiber of everyday activities — schooling, housing, medical care, public transportation — and elevated personal prejudices into the realm of legality. It raised white and black children in separate environments, entrenching prejudice so deeply that we, in 2019, are still reeling from its consequences.

Steve Luxenberg’s captivating history Separate: The Story of Plessy v. Ferguson, and America’s Journey From Slavery to Segregation is a slow-build up to the case itself. (Homer Plessy, the Creole plaintiff who attempted to sit in a railroad car for white passengers, comes into the story 60 pages before the end.) Luxenberg is more concerned with the legal and social entanglements that led up to the case, a myriad of state-specific practices upon a wide spectrum of public prejudice.

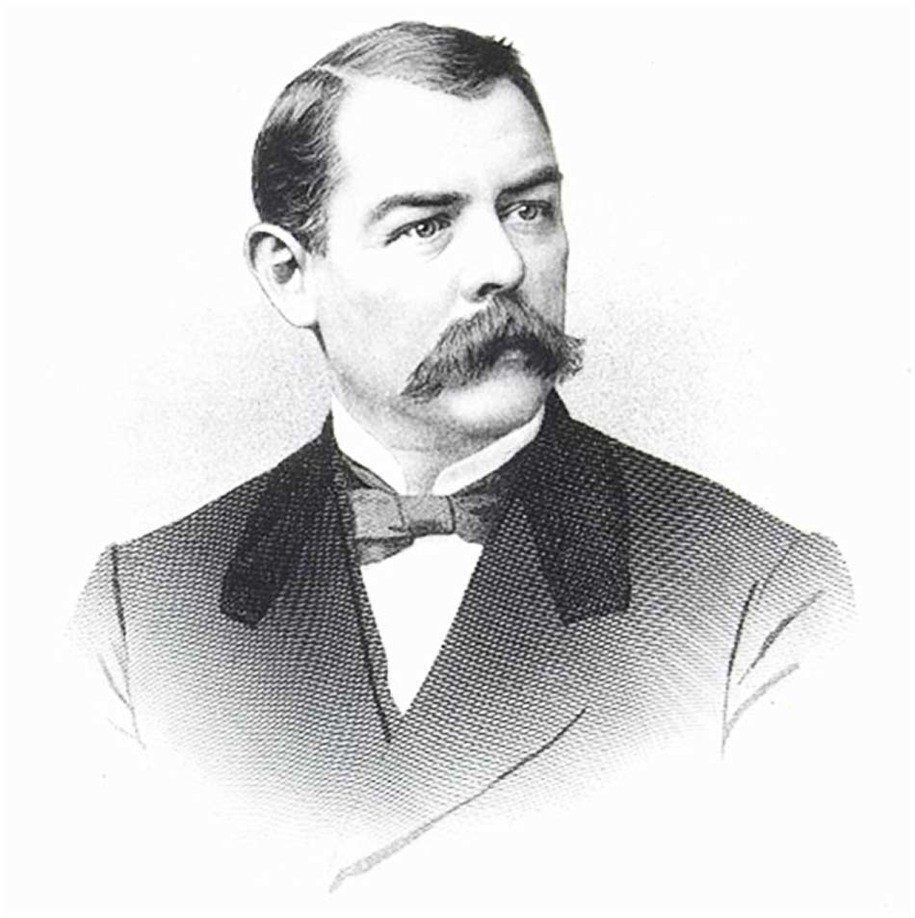

Separate follows the lives of three men crucial to the outcome of the decision — the firebrand white Northern journalist Albion Tourgée and Supreme Court justices Henry Billings Brown and John Marshall Harlan. From different states and backgrounds, the stories of these three men hurtle towards that fated moment in 1896 when their collective experiences lead to a damaging climax.

The fourth protagonist — and certainly the most interesting — are the people of color in New Orleans in the late 19th century.

‘Separate but equal’ policies were commonplace on the state level throughout the South and especially contentious when it came to public transportation — streetcar and railroad passenger cars. Drivers and ticket takers had to determine on the spot the race of a passenger, guide them to the ‘proper’ section and enforce the separation should there be conflict.

But in Louisiana, there were thousands of residents of color who had never been enslaved people, les gens de couleur libres with a mix of European and African ancestry. (An excerpt of a 1853 New Orleans divvied its population into eight different ‘grades’.) Passengers could be labeled black one day, white the next, depending on the railroad or streetcar employee making the determination.

Plessy was indeed a mixed race gentlemen from New Orleans, and his ‘test case’, destined for the high court, would be shepherded through the system by Tourgée, a nationally known columnist, and Louis Martinet, a Creole attorney with interesting challenges to his own career.

In the stories of Brown and Harlan, another fascinating subplot emerges, that of wavering and unexpected shifting views on slavery and racial relationships, inspired by unique state issues following the Civil War.

And even enlightened views can be reached narrowly. Harlan, the ‘lone dissenter’ in the case of Plessy vs. Ferguson, was once a proud member of the anti-immigrant Know Nothing Party and was a full-throated supporter of the Chinese Exclusion Act.

For many legal minds in the late 19th century, equality in a legal sense did not mean social equality. An American, white or black, may share the same rights as upheld by the U.S. Constitution, but in everyday matters, there was no urgent need to include all people in the same public spaces.

Of course this would prove dysfunctional and absurd, a fallacy based on an unenforceable belief that every actor at every level of public life would truly provide ‘equal’ options to Americans of any color. Separate lays out the course for how this thinking became the law of the land.