Before it closed in 2011, the Coliseum Cinema in Washington Heights proclaimed itself to be the ‘New York City’s oldest operating movie theater’. When it was first constructed in 1920, its stage would have hosted vaudeville acts as well as silent motion pictures.

But few films that ever premiered at the Coliseum would depict events as torrent or as dramatic as those that took place in the structure that stood on this spot many, many decades before.

An old stone tavern once stood high upon the bluffs of Upper Manhattan, in an area many years later referred to as Washington Heights.

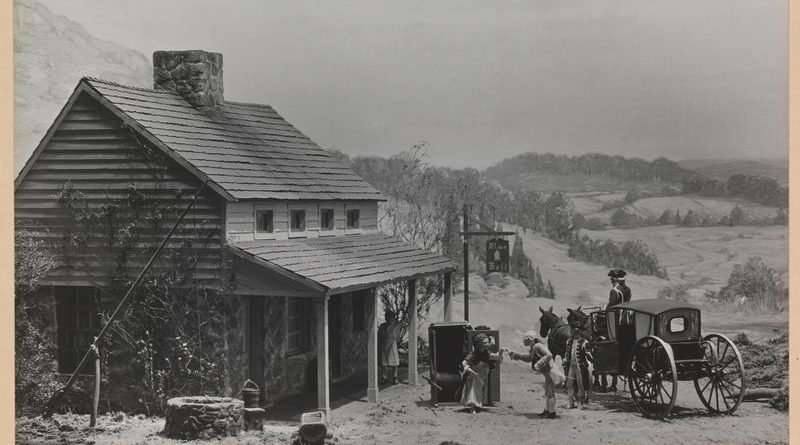

The Blue Bell Tavern sat off Bloomingdale Road nestled in a grove of trees, a modest two-story dwelling alight at all hours with wanderers. New York travelers often passed it as they headed towards the King’s Bridge, a toll bridge over Spuyten Duyvil Creek.

To truly envision this gothic place in its natural environment, you have to picture Washington Heights before there was ever a Washington there — a lush, high ridge thick with trees, a natural vantage offering unobstructed views of the entire region.

Like the skyscraper observation decks today, a visitor could seemingly see the entire world from here.

One cold, stormy night some evening in November 1783, a damp and exhausted figure strode up to the door, a young woman who had escaped from her home many miles away.

She was there to meet her lover who had already arrived at the Blue Bell, a man soaked, in disarray and wearing what certainly would have been a common sight for the day — a British uniform.

This man was a sergeant in the British military stationed in the Hudson River Valley. But the army was now retreating. Indeed, they were leaving New York that very month.

The sergeant had fallen in love with this woman, a resident of colonial New York, who (as these sort of stories go) we know little about. We do know her parents disapproved of the British sergeant and would only relent to their marriage if he agreed to desert the army and remain in the United States.

On that rainy evening, the sergeant and his beleaguered love took each other in their arms and were finally married — here at the Blue Bell Tavern. As the story goes, it was a Quaker ceremony, for there were no other officiators that night at the tavern.

The Blue Bell, once situated at today’s intersection of 181st Street and Broadway, was built in mid 1720s as a home and renovated into the type of pleasant inn that, by 1753, the venerable Cadwallader Colden (not the former mayor, but his grandfather and later governor of New York) could find “very comfortable” food and lodging here with his friend James Delancey, the state’s lieutenant governor.

The tavern might have faded peacefully into oblivion if not for the Revolutionary War. When angry New Yorkers attacked the King George statue in Bowling Green at the foot of the island, his stone head ended up on a pole in front of the Blue Bell.

A View of the Attack against Fort Washington and Rebel Redouts near New York on November 16, 1776

While the Continental Army fled from Manhattan during the month of September 1776, officers stationed here at the Blue Bell assessed their grim situation and coordinated the army’s next steps.

With the tavern located so close to a key pathway out of town, it also became a headquarters and lodging for British officers long after Washington’s army abandoned the city. At one point, even Colonel William Howe, head of the British forces, himself stayed here.

Flash forward to November of 1783 — Washington and his now victorious army were now preparing to re-enter New York, this time to push the British out of town and experience a new, free American nation from the vantage of the ravaged port city. “I remember well our march up the hill, and the noble appearance of George Washington as he sat on his big bay horse,” said a veteran of the war in Appleton’s Journal.

George would even stay for an evening at the Blue Bell, awakening early to prepare his army’s grand entry down Bloomingdale Road and into the city. (Another important tavern of the day, the Bull’s Head, would also play a prominent role in Washington’s arrival into the city.) But on that day, they would add two more people to their procession.

That British deserter and his new bride — the ones whose rendezvous at the Blue Bell led to their Quaker marriage — now emerged from behind the building and called out Washington’s name.

Given his rumpled British uniform, this certainly created quite an uproar among Washington’s attaché. The pair were taken into custody, and the British officer recounted his romantic tale to his captors. Washington and his men learned that:

“…the young man was a sergeant (which the chevron on his sleeve indicated) who had for some time loved and was betrothed to the young woman who was with him; that her parents, who lived in the city would not consent to her marriage unless he would stay in this country; that they had arranged a plan a few days before for a desertion on his part and an elopement on here; that they were to meet at the Blue Bell and be married, and there wait for the protection of approaching American troops. Their plan had worked well.

— Appleton’s Journal, 1873

The sergeant wished to desert the army and join the Americans if only they would provide protection for him and his young bride. Indeed, with so many Loyalists still in the city, the soldier’s betrayal would certainly have been met with retaliation.

In desperation, the sergeant and his new bride showed Washington’s men their newly inked marriage certificate and begged for mercy

In fact, the tale apparently amused Washington and his men, flush with the excitement of victory. “A bard” among Washington’s men even wrote a poem in the couple’s honor. You can read the whole thing here, though it begins:

“A soldier and a maiden fair,

Helped by shy little Cupid,

Fled from the camp and momma’s chair,

(Such guardians, how stupid!),

And to the Blue Bell did repair,

To have themselves a-looped.”

We can assume with the lighthearted tone of the poem that things turned out well for the happy couple. They were allowed to accompany Washington on his entry into the city the following day.

The Blue Bell miniature, displayed at the Museum of the City of New York when it opened the doors to its new Fifth Avenue home in 1930.

BThe old tavern passed through many owners (and many names) through the 19th century and eventually returned to its original purpose as a residence. One old source suggests that the building burned to the ground in 1876, though it may have survived this blaze into the new century.

Whatever structure stood here then was finally torn down by 1915. But tales of the Blue Bell entered nostalgic accounts of the Revolutionary War almost immediately, as 19th century historians struggled to piece together the American narrative from those who still remembered it.

The Blue Bell lived on long after its demolition in a most curious way — as a well-known miniature housed at the Museum of the City of New York.

An issue of Popular Science Magazine from 1930 observes the construction and installation of the Blue Bell exhibit, which made its debut that year in the museum’s new home on Fifth Avenue and 103rd Street.

The Coliseum in 1922, Museum of the City of New York

For many decades, you could go to the former spot of the Blue Bell Tavern and experience a Gothic romance of your own. Standing on that spot today is the abandoned RKO Coliseum, once one of Manhattan’s largest movie theaters.