One hundred and fifty-five years ago (on July 13, 1865), New York City lost one of its most famous, most imaginative and most politically incorrect attractions.

When P.T. Barnum opened his museum in 1841, the kooky curiosities contained within the building at the corner of Broadway and Ann Street — at the foot of Park Row — were simply reconstituted properties from other museums.

But he soon expanded the collection to include living spectacles, both human and animal, become both the greatest show and the greatest side-show on earth.

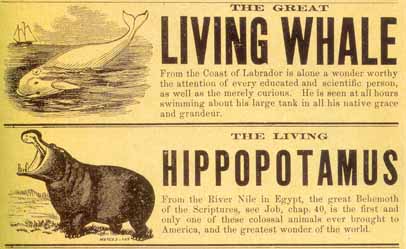

From his lilliputian stars Tom Thumb and Commodore Nutt to the unfortunate white whales contained in water tanks in the basement, Barnum’s American Museum was New York’s destination for the fascinating and the weird.

Millions would visit its corridors during its two and a half decades of operation. It was so renown that it was even a target of attempted sabotage during the Civil War.

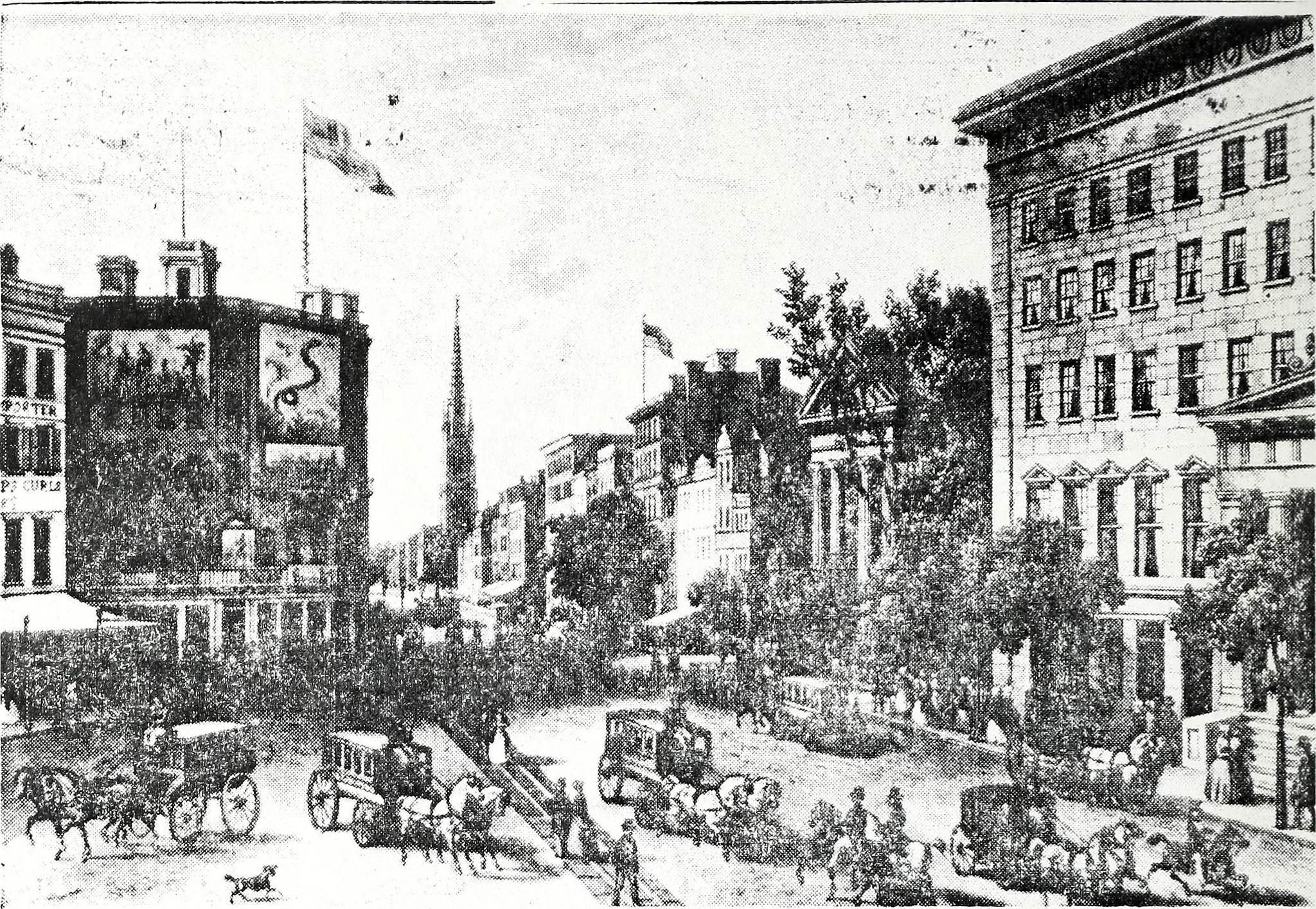

Below: A rare photo of Barnum’s American Museum, taken in 1858

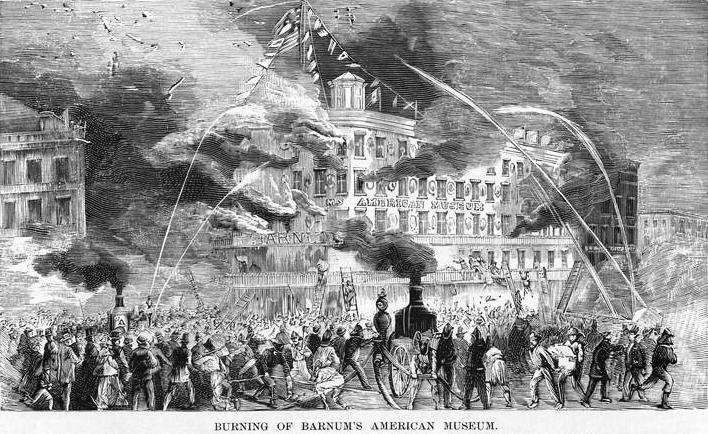

At around noon on July 13, 1865, the building quickly succumbed to “the fierce tooth of fire,” causing the greatest pandemonium that New York City had ever seen. I must give way to some of the press reports of the day, as they best capture the drama:

New York Times: “Probably no building in New-York was better known, inside and out, to our citizens than the ill-looking ungainly, rambling structure on the corner of Broadway and Ann-streets, known as the American Museum, where for more than twenty years Mr. Barnum has furnished the public with a wonderful variety of amusements.”

Below: The street scene at the cross-section of Broadway and Ann Street, in 1860. A sign advertising Barnum’s snake collection can be seen on the museum.

New York Sun: “About half past twelve o’clock yesterday the Engineer rushed up from below announcing that his room was on fire, and about the same time immense volumes of smoke permeated the Ann Street end of the building. [K]nowing that the immense whale tank was directly over the spot where the fire had begun to make headway, attempted to knock a hole in the huge reservoir.”

The occupants of the tanks were doomed. “‘[T]wo whales, imported, at a cost of $7,000, from the coast of Labrador,’ whose sportive plunges and animated contests of affection afforded constant amusement to hundreds of spectators, [was] a pregnant contrast to the fearful death by roasting which they so soon thereafter met.”

The fire spread rapidly, quickly filling the upper floors with smoke. Â Firemen burst in from the Ann Street side and quickly attended to patrons who had collapsed or were too confused in the immense labyrinth of bizarre objects to escape.

A fireman named William McNamara is credited with single-handedly evacuating many patrons of the museum, not to mention some of the performers who regularly lived there.

From the New York Sun: “Knowing that [some performers] occupied apartments on the third floor, he rushed thither and burst open the doors. Finding the rooms empty he ascended to the next floor and succeeded in bringing down the ladies assembled in the dressing rooms there — a Miss Swan, the Giantess, and Miss Zuruby Hannus, the Circassian girl.”

Below: Anna Swan, ‘the Giantess’ who lived at the museum, was successfully rescued

Many of the wax figures from the third floor were hurled out the windows. One peculiar item captured the imagination of the crowd — the wax depiction of Jefferson Davis, dressed in a woman’s petticoat. (It was rumored that the former president of the Confederacy has attempted to escape dressed as a lady.)

NYT: “One [rescuer] had Jefferson Davis’ effigy in his arms and fought vigorously to preserve the worthless thing, as though it were a gem of rare value. On reaching the balcony the man, perceiving that either the inanimate Jefferson or himself must go by the board, hurled the scarecrow to the iconoclasts in the street. As Jefferson made his perilous descent, his petticoats again played him false, and as the wind blow them about, the imposture of the figure was exposed.”

NYS: “When the Jefferson Davis petticoated figure was recognized by the crowd, it was seized, kicked, knocked and finally hanged to an awning frame [in front of St. Paul’s Church], amid the derisive and contumelious epithets of the persons engaged in this pastime.”

More seriously a great number of artifacts from the Revolutionary War were incinerated in the fire. “Valuable mementos of Washington, Putnam, Greene, Marion, Andre, Cornwallis, Howe, Burr, Clinton, Jefferson, Adams, and other eminent men which should have been carefully stored in a fire-proof vault, yesterday smoldered in the heat….” [NYT]

The museum’s impressive collection of taxidermy — monkeys, lions, elephants, zebras — were swallowed up by smoke and collapsed into the inferno.

But the museum also had a great many living animals — snakes, pigs, dogs, and even a kangaroo and an alligator. And, of course, a great many monkeys — “big monkeys, little monkeys, monkeys of every degree of tail, old, grave, gray monkeys, young, rascally, mischievous monkeys, middle-aged, scheming monkeys, and a great many miserable, angry monkeys.” Most perished in the flames although some escaped into the streets, some never to be found again.

Below: This is Harpers Weekly’s illustration of Barnum’s second fire — see below — but could have tragically captured the events on July 13, 1865.

Remarkably, nobody humans died in the blaze. In fact, few wax depictions of humans perished as many took to rescuing wax figures thinking they were alive. The fire spread to several surrounding buildings, and soon the entire block was engulfed in flame.

NYT: “The roof of the Museum had now fallen, and the interior of the building was like the crater of a volcano. A stream of heated air issued from the top, and was borne eastward by the breeze directly over the block, carrying with it light articles, pieces of burning wood, shingles ….

At 1:30 came a crash resounding like the explosion of a powder magazine. The whole wall on the Ann-street side had fallen. A cloud of dust and smoke filled the air, making it dark as twilight, and rendering it impossible to descry objects at short distance.”

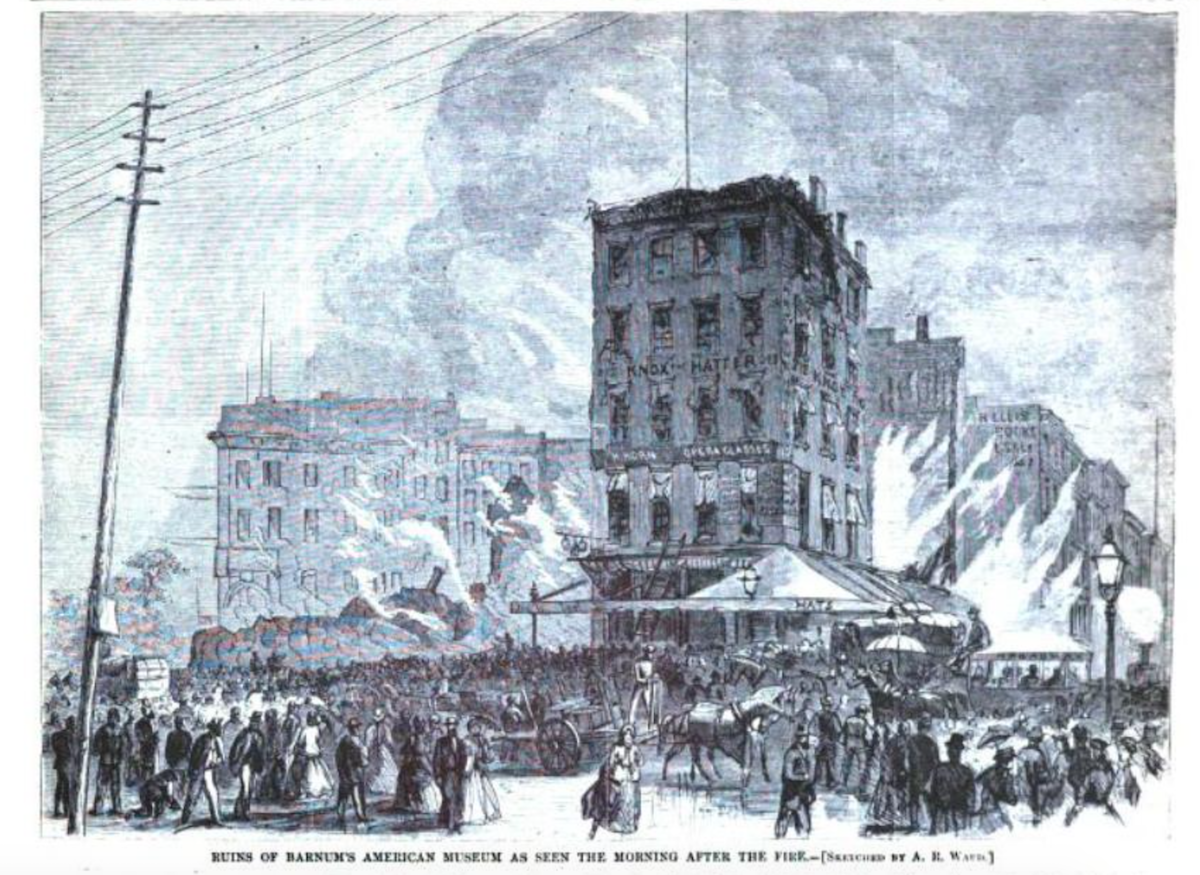

Notable among the surrounding buildings that were damaged was the famous Knox the Hatter at 212 Broadway. Fortunately for the fate of New York, the Croton Aqueduct water system had been installed two decades earlier, allowing the blaze to be put out with some speed, preventing a repeat of the Great Fire of 1835.

There was a bit a looting, including “two men dressed as soldiers [who] were seen coming out of the shoe-store in Ann Street, each with five or six pairs of shoes under their coats.” And there were false reports that the lion has escaped and was running through the streets.

For years after, people mourned the loss of Barnum’s collection, truly among the greatest in New York City up until that time. Â Barnum attempted to relaunch the museum at 539-541 Broadway. but it, too, was destroyed in a fire (pictured below).

Then, in 1871, he leased a train depot and called it Barnum’s Monster Classical and Geological Hippodrome. (It would later morph into the first Madison Square Garden.)

Finally he just decided to take his collection of acts on the road forming a traveling circus in 1881 with ringmaster James Anthony Bailey.

While the world of entertainment would be changed by their collaboration — Barnum and Bailey’s Circus — most would consider the old American Museum as Barnum’s greatest achievement.

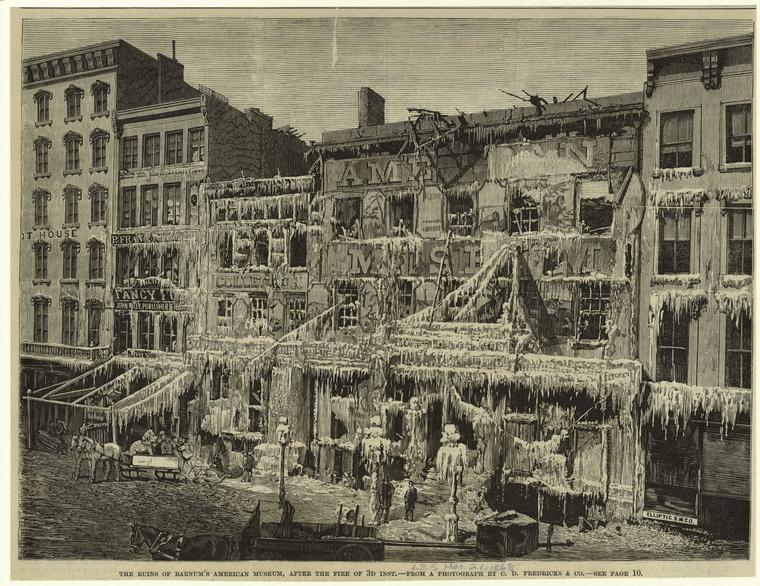

Below: Barnum’s second museum destroyed by fire, which gutted the building on a cold day

For more information, we have a few Barnum-themed podcasts that you might enjoy:

4 replies on “The fire at Barnum’s American Museum 155 years ago”

For more about Barnum, read AH Saxon’s definitive biography of this magnificent man, as well as consult the relevant indexed pgs in my “Butchery on Bond Street” and “East in Eden: William Niblo and His Pleasure Garden of Yore” Bailey’s free-standing mansion still stands in Harlem at 150th St and St Nicholas Terrace

Thank you Benjamin! I’ve been meaning to read that Barnum book forever…..

What are the details of the attempted arson? What caused the two fires?

[…] around noon on July 13, 1865, a fire broke out at the […]