Arbuckle’s Deep Sea Hotel was neither in the deep sea, nor was it a hotel. But for hundreds of young, single women at the end of the Gilded Age, it was home.

The Challenges of Living Single

Accommodations were indeed limited for the thousands of young single women who arrived in New York City at the start of the 20th century.

Wealthier single ladies could enjoy a degree of independence by indulging in fashionable apartment living. Affordable options like boarding houses were often socially binding.

For instance, the morality-minded YWCA housed hundreds of New York women by the 1890s. It was often too expensive to rent on your own place, even with roommates, and the neighborhoods where such housing was available would not have been too desirable.

Enter Brooklyn coffee millionaire John Arbuckle.

A Caffeine Jolt

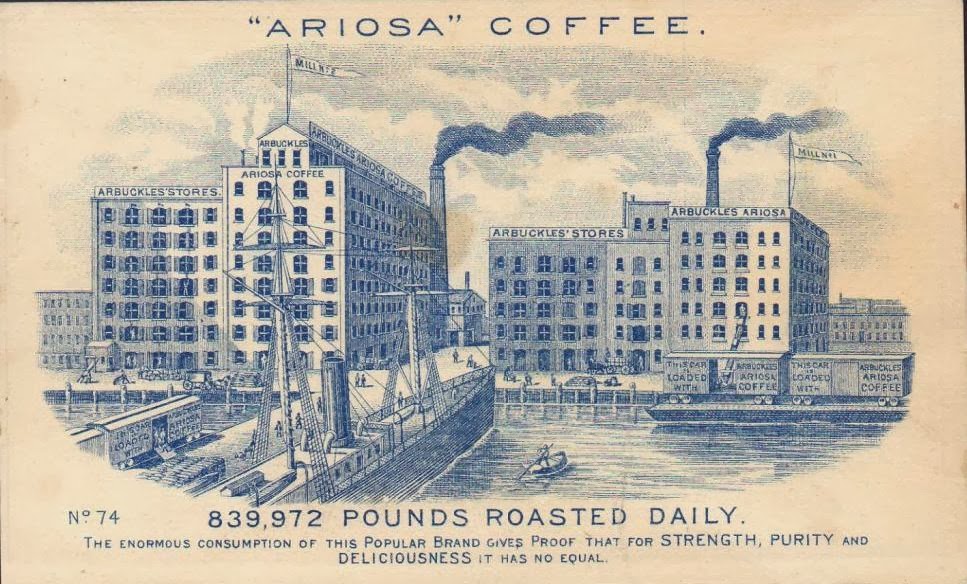

The sugar manufacturer, already a chief competitor of William Havemayer, innovated the mass production of coffee by the 1890s, making himself extremely wealthy and jumpstarting America’s love affair with coffee in the process.

His Jay Street plants and Water Street warehouses dominated the Brooklyn waterfront in the area of today’s DUMBO.

In emulation of other progressive-minded New York philanthropists, Arbuckle commissioned free water-bound excursions for the overcrowded poor of the Lower East Side.

However, when a steamboat owned by another company — the PS General Slocum — exploded during one such excursion in 1904, killing over 1,000 people, such trips quickly went out of fashion.

Arbuckle then decided to use one of his ships in a more unconventional way — a long-term hotel for single women.

The Floating Hotel

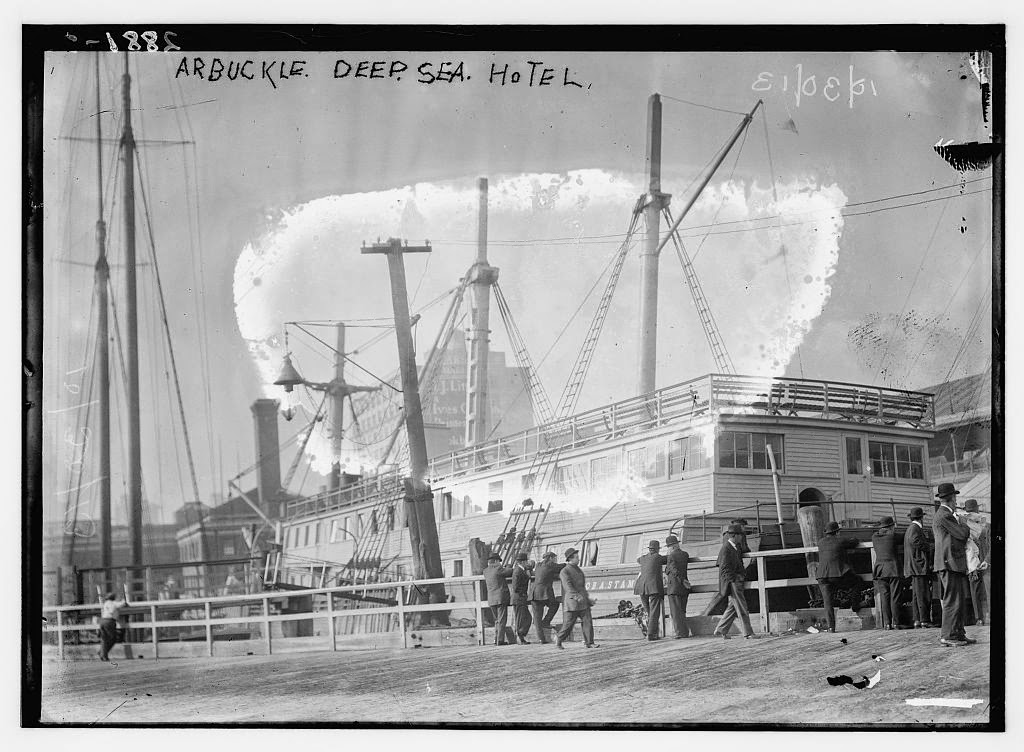

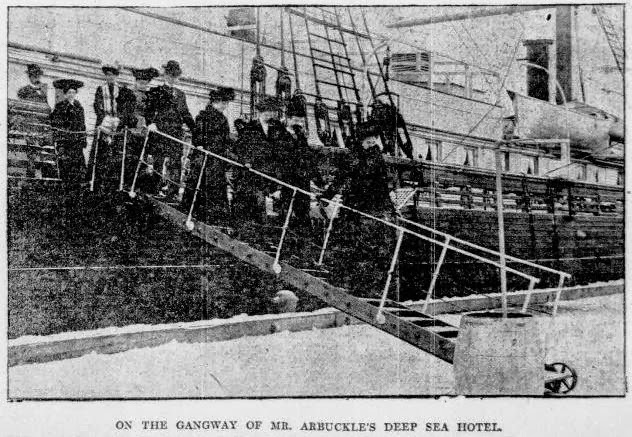

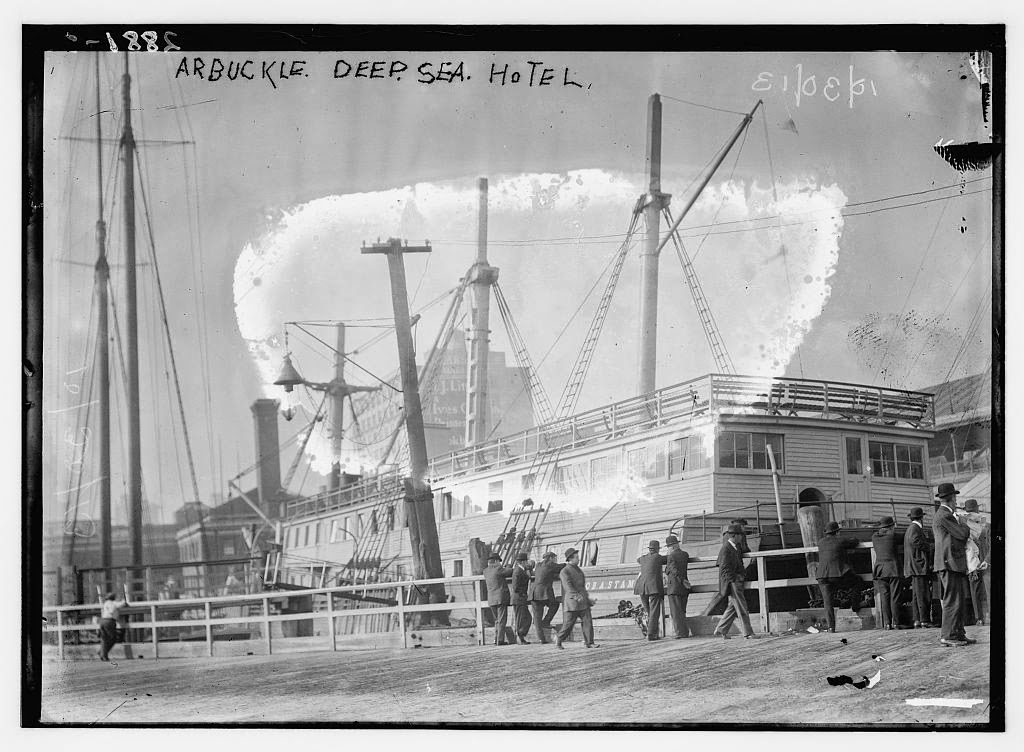

His ship the Jacob A. Stampler was turned into a floating hotel for one hundred women, with a smaller ship nearby for young working men. It was docked at West 21 Street on the Hudson River, near the massive piers for passengers liners.

“The fundamental idea of this hotel scheme,” according the New York Tribune in 1905, “is to benefit young men and young women who are receiving low wages and are striving to live respectable lives.”

In 1905, its first year of operation, women paid “40 cents a day, or $2.80 a week, while the young men pay 50 cents a day or $3.50 a week.” [source]

From the Tribune profile:

While both genders benefited from the unusual hotel idea, Arbuckle’s focus was in the assistance of women.

“A young fellow can fight for himself and get along his own way,” said the millionaire, “but it is different with a woman or girl confronted with problem of keeping herself respectable while working for low wages.”

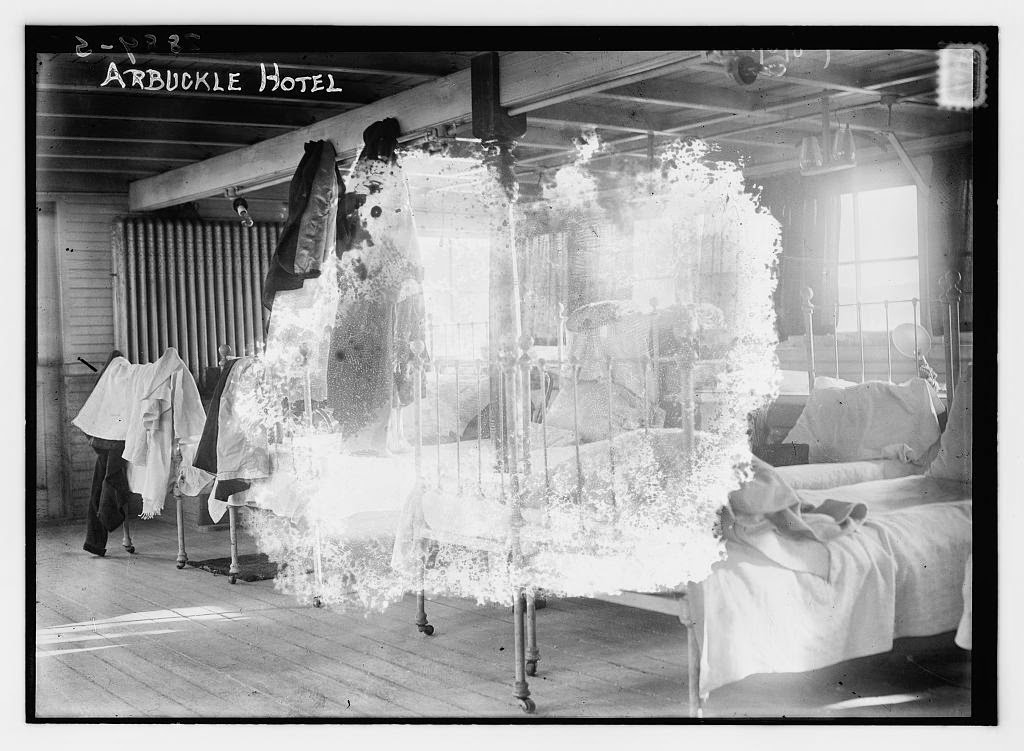

The women were fed well and provided a selection of magazines and newspapers, not to mention a piano for Sunday evening sing-alongs. They were also given sewing machines and laundry facilities.

The rocking of the boat and the relative bustle of a busy pier seems not to have bothered Arbuckle’s early tenants.

“It’s so quiet here. No rattle and roar from the streets,” said one young woman. [source] Ladies could receive gentlemen callers, but men had to vacate by 10 pm. As many women worked quite late in the day, this probably didn’t amount to much socializing.

A House and a Vacation Home

During the summer, the boat actually did take regular trips to various places in the region, from Coney Island to the shore of Staten Island.

In July, the two floating hotels would head out to Coney Island every day, docking for a couple hours at Dreamland amusement park.

Surmising from its frequent journeys, I imagine Arbuckle’s floating hotels had few long-term summer tenants in these early days.

Below: The dining room and the sleeping quarters of the Deep Sea Hotel, circa 1913 (LOC)

The Final Days

Over the next ten years, the Deep Sea Hotel took fewer trips, becoming more or less a semi-permanent, floating apartment complex.

It was referred to by this point as the Working Girls Hotel.

At some point, perhaps due to overwhelming traffic at the Chelsea piers, the Stampler made the east side its home, regularly docking at East 23rd Street.

The floating hotel never really made a profit, and after Arbuckle died in 1912, his inheritors attempted to shut it down.

I should also note that the Stampler was a very, very old boat.

“[The] ship was beginning to rot and soon would be unsafe,” said the New York Sun. The women who lived there, however, fought successfully to keep it open until 1915, when they were finally told to permanently disembark.

Interesting fact to note about its final days — both single men and women lived aboard the boat by 1915.

Its last documented population was 50 girls and 16 boys, according to the Sun. (Most likely teenagers or adults in their early twenties.) The ship rarely sailed to Coney Island in the summer, but had become a destination in itself.

“One of the five decks is fitted up as a dance hall,” “crowded every night with dancers” when music from a nearby pier begins to play.

The price of rent these days!

The last tenants finally left on September 1, 1915, with many unable to find further housing. “There isn’t a girl on this boat that makes $9 a week,” said one mournful tenant, “and you know how far that goes in this city.” [source]

By 1917, the Stampler was a rotted breakwater off of Bayville Beach in Oyster Bay. To this day, perhaps, some remnant of the ship still sits in the water off the coast of Long Island.

By the way, Arbuckle may no longer sponsor floating housing accommodations for working people, but they still make coffee.

1 reply on “The Deep Sea Hotel: A nautical housing solution for independent women”

Have you already done a pod cast on this or is there one coming up.I would definitely like the hear this