With a new mayoral race on the horizon in New York City we think it is time that you Know Your Mayors! Become familiar with other men who’ve held the job, from the ultra-powerful to the political puppets, the most effective to the most useless leaders in New York City history.

This longtime feature of this website is being rebooted with new articles and newly researched and refreshed earlier entries in this series. Check back every other week for a new installment.

Dewitt Clinton was so much more than a mayor of New York City of course.

He also served as a two-term governor, ran for president against James Madison and helped oversee one of the greatest engineering projects in American history.

He negotiated the choppy waters of early American politics with dexterity, building upon the reputation of his family name to fuel economic and cultural growth in the state he called home.

His greatest achievement was the Erie Canal, the cross-state canal which linked the Hudson River and New York Harbor with the interior of the United States.

No other civic project — with the possible exception, at the start of the 20th century, of the subway system — would affect the fortunes of New York City in such a dramatic and unambiguous way.

So, yes, the many accomplishments in Clinton’s storied career tend to overshadow his work as the mayor of New York.

Yet most historians place him among the greatest mayors the city has ever employed. He might even be the greatest in terms of his long-term impact.

Clinton served ten one-year terms non-consecutively — 1803-1807, 1808-1810 and 1811-1815 — weaving together an extraordinary period of city growth during tumultuous political times and a potentially deadly foreign war. (Why not consecutive terms? I’ll explain in the next Know Your Mayors column.)

Clinton on the Rise

Dewitt Clinton was born in Little Britain, New York, on March 2, 1769, into one of the most politically important families in America.

Major-General James Clinton, DeWitt’s father, fought next to George Washington during the Revolutionary War (and brutally killed hundreds of Iroquois people during the 1779 Sullivan Expedition). DeWitt’s uncle George Clinton rose the political ranks following the war to become the governor of New York (from 1777-1795 and again from 1801-1804).

By the 1890s, according to author Evan Cornog, “three families presided over New York State politics — the Schuylers, the Clintons and the Livingston.”

So DeWitt Clinton had easy access to the corridors of power — Uncle George even made him his secretary in a bold gesture of nepotism — but he built upon that privilege, instead of resting on it. More importantly, he’s often considered to have the genuine needs of New Yorkers in mind in his accumulation of power, believing the city’s cultural and economic prosperity could be worn as a badge of honor for himself.

His most influential job during this period was as a member of the Council of Appointment, the body charged with appointing all the governmental positions that were not elected. This included the mayor of New York. In fact, he helped appoint the last mayor in our Know Your Mayors series — Edward Livingston.

While the Clintons were aligned with Thomas Jefferson and the Democratic-Republicans, DeWitt held personal animus towards his party’s Aaron Burr, the Vice President, who many believed had attempted to steal the 1800 election from the preordained Jefferson. When Burr killed Alexander Hamilton in 1804, Jefferson replaced him — with George Clinton, DeWitt’s uncle.

By then, DeWitt himself had dabbled in federal office, serving as the Senator from New York for almost two years from 1802 to 1803. But he hated Washington D.C. — which was an unpleasant and barely developed swamp then — and wanted to return to the comforts of New York.

So he resigned and took a new job which was then offered to him — the mayor of New York City.

Setting the Foundations

At first it appeared this was just another step in the political ladder for DeWitt. According to Gotham, Clinton told his uncle that “being mayor was the better job [than being a U.S. senator] because its influence in presidential elections made it ‘among the most important positions in the United States’.”

But he quickly fleshed out the mayor’s role in surprising ways, having the unique political connections that allowed him to expand local government’s role. In later years, these expanded powers would be reduced by the influence of political machines like Tammany Hall.

Among the fledgling organizations he either founded or vigorously supported during his time in office:

— New York Board of Health: Clinton entered office with yellow fever the city’s greatest enemy. According to NYC Health, “Led by Mayor De Witt Clinton, the board evacuated stricken neighborhoods and started collecting mortality statistics, to ‘furnish data for reflection and calculation.'”

From this department came a newly created role — city inspector — which expanded to collect data (births, marriages and deaths) on city residents.

— New-York Historical Society: Clinton believed in upgrading the city’s cultural life, and the Historical Society, essentially New York’s first museum, allowed the city to celebrate its role in the new American cause and exalt the New Yorkers who fought for independence (which naturally included Clinton’s family).

Clinton was a founding committee member in 1804 and even gave the institution some space at City Hall (then at Wall Street aka Federal Hall).

He also chaired both the American Academy of the Arts and the Literary and Philosophical Society in their early years.

— Free School Society: Clinton championed the social education model which eventually became the New York public school system.

According to Evan Cornog, “In 1805, two measures transformed primary education in New York. The first was the allotment by the legislature of 500,000 acres of state lands and three thousand shares of bank stock for the benefit of public school. The second was the establishment of the New York Free School Society, whose president, from its inception to his death, was DeWitt Clinton.”

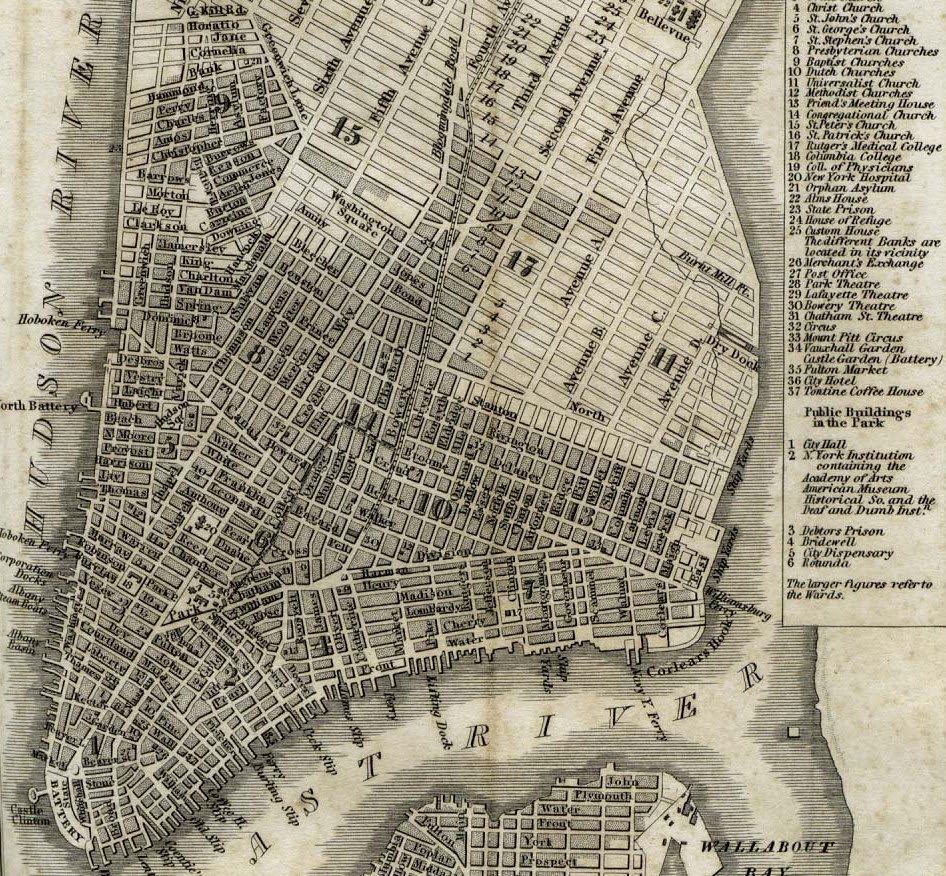

— The Grid Plan: Seeing a need to plan the city’s growth as it galloped up Manhattan island, the city’s Common Council formed a committee — “doubtless at DeWitt Clinton’s instigation” — that would draft up ideas for a possible grid of streets and avenues.

By 1811 Clinton would sign the Commissioner’s Plan into operation.

— A System of Fortifications: In addition, Clinton faced the impending crisis of a new war with Great Britain. Although the War of 1812 never came to New York City, Clinton oversaw the construction of new fortifications through the city, including a new fort at the Battery which eventually bore his name — Castle Clinton.

A Complicated Record

Clinton innovated a form of governance which can be seen either as forward thinking or incredibly opportunistic (and quite possibly both) — the improved rights of immigrants.

Christian Luswanger, a member of the city’s night watch, became the first officer killed in the line of duty in New York during a Christmas Day anti-Catholic riot in 1806, the most violent of a series of skirmishes aimed at immigrants. New Irish arrivals faced Nativist backlash in a heavily Protestant city.

The mayor, however, was a supporter of the Irish, laying the groundwork for one of the most successful collaborations in 19th century New York City politics.

As a U.S. senator, Clinton had supported liberal immigration laws. As mayor he also supported the elimination of a citizenship test oath for Catholics. As a result, his opponents quickly painted Clinton as a puppet of foreign influence.

But Clinton was no paragon of human rights reform. While he earlier supported the Gradual Emancipation Act of 1799 — and a second Emancipation Act passed in his first year as governor in 1817 — his family had kept enslaved people for decades. And DeWitt himself owned at least a couple people during his years as mayor, including a coachman named Henry.

And many decisions Clinton made did seem more bluntly opportunistic.

He directed that the city’s funds be held by the banks of Manhattan Company, formed in 1799 — by his foe Aaron Burr, no less — to build a water system for the city. But the Company never did fund a truly adequate system, existing only as a bank. (Clinton, by the way, was also a company director. Seems like a conflict of interest!)

The Billion Dollar Idea

For decades, prominent New Yorkers had pondered the idea of an upstate canal system, and even Clinton had considered canal making schemes years before reaching any significant prominence, extending back to his days as a student at Columbia College.

His interest in a massive canal project was renewed during his tenure as mayor (and those years in between his non-consecutive terms). By the time he became the governor of New York in 1817, he was so associated with the canal project that it became known by detractors as Clinton’s Folly.

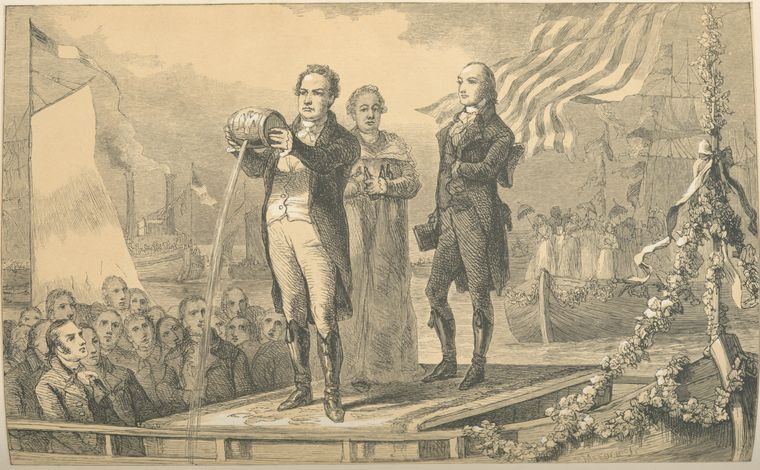

No folly at all. When the Erie Canal finally opened in 1825, the engineering marvel — one of America’s greatest early achievements — proved genius. It not only created new wealth of New York City, it boosted the economic strength of the entire country.

Clinton had created new opportunities for New York City. The rise of the city as an economic and cultural power begins with him.

For more information on DeWitt Clinton, we have an older show in our catalog on Clinton and his role in creating the Erie Canal:

5 replies on “Meet Mayor DeWitt Clinton, the man who built New York City’s future”

Looks eerily like British Prime Minister David Cameron. Thanks for an absolutely brilliant podcast.

This is so exciting and interesting to see!! I will pass this onto family to view!! Dewitt Clinton is my great 3X grandfather. My mother has a diary of his that is quite interesting about his trip on a boat from England. Holley Hackett Hall

Great podcast! A nice look at the man behind the Erie Canal!

Greg, was this this Clinton who gave his valedictorian speech in Latin in the presence of George Washington and the Founding Fathers? I get those Clintons mixed up!

I am never bored with these podcasts! Dewitt Clinton was so important in the development of NYC. I imagine him at 8 years old in the middle of a much tinier NYC during the American Revolution!!! It gave him a sense of purpose, guts, necessity and dogged will power. He was creative, too. He had a solid cushion from which to perch… in his family’s importance and their financial security. But perch he did not. He was a man on the go!!! A true NEW YORKER!