We’re just months away from a new mayor in New York City so we think it is time that you Know Your Mayors! Become familiar with other men who’ve held the job, from the ultra-powerful to the political puppets, the most effective to the most useless leaders in New York City history.

This longtime feature of this website is being rebooted with new articles and newly researched and refreshed earlier entries in this series. Check back every other week for a new installment. Read past articles here.

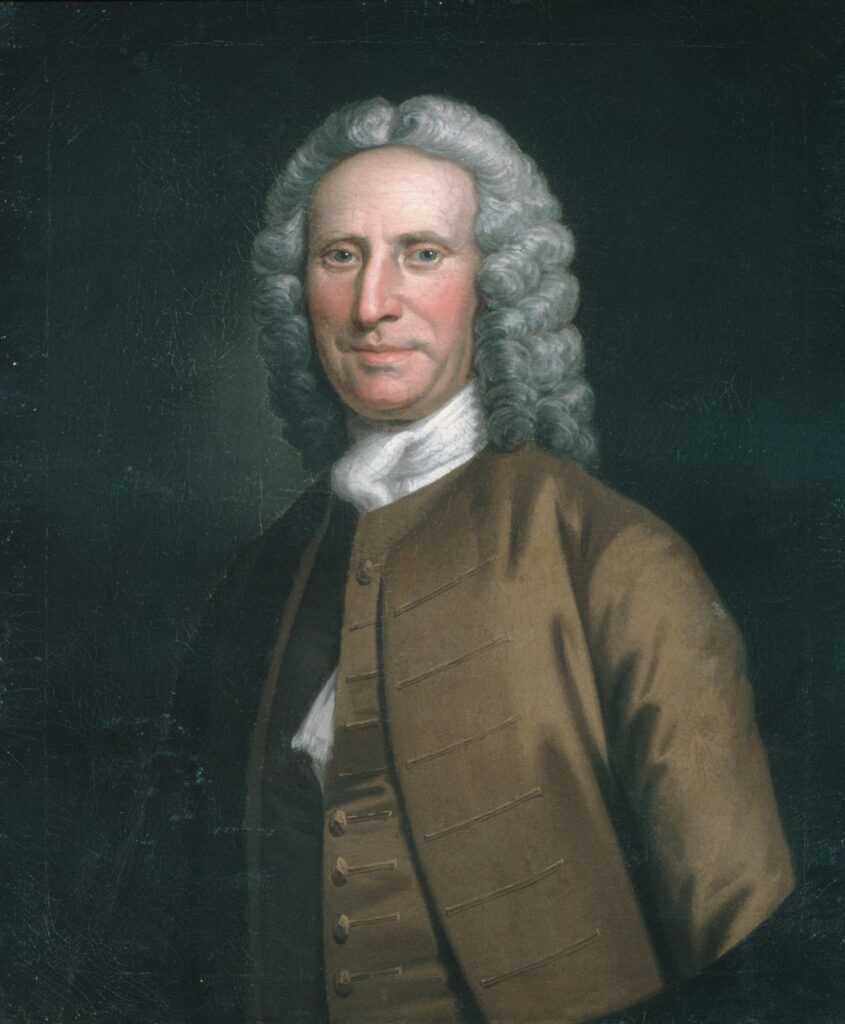

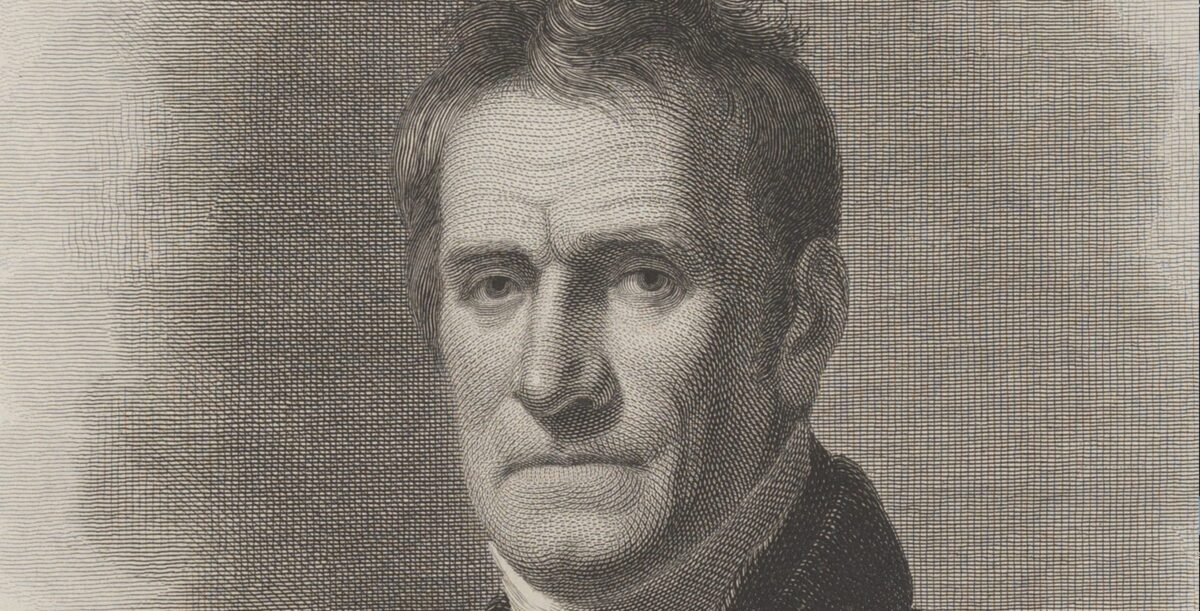

Cadwallader D. Colden

Terms: 1818-1821

The most remarkable thing about New York City having a mayor named Cadwallader Colden is the fact that he was not even the most famous New Yorker named Cadwallader Colden.

That distinction goes to his grandfather, an altogether different Cadwallader Colden than his grandson and a rather fascinating Renaissance man.

Well, despite the fact that he was also pro-British, stridently hated among the American rebels and the type of man that would have thrown most of us in jail on sight.

Grandpa Colden

Ole Cadwallader was an Irish physician who came to the American colonies in 1710 (at age 22) to practice medicine.

Establishing his practice in Philadelphia, he later came to New York and in 1743 wrote a now seemingly obvious treatise drawing a connection between New York’s unsanitary conditions and its frequent outbreaks of yellow fever.

Elder Colden became governor of the New York colony in 1760 and later sparked ire among beleaguered New Yorkers, who burned his effigy over enactment of the Stamp Act.

Colden ultimately represented the losing side of the American Revolution, and due to that, his other accomplishments are often overlooked. He was the first in America to write about Newtonian scientific theories and the first colonist to act as ambassador to the Iroquois Confederacy, the union of five Native American tribes.

Grandson in a New County

Perhaps it’s fitting that Colden died in September 1776, the year of the conflict that would run the British out forever.

He might be scandalized to know that his grandson, born in 1769 in Flushing, Queens County, would become a model American. (The child’s father Cadwallader Colden II was more concerned with governing the family’s lush 3,000 acre estate in Queens and remained essentially neutral during the Revolutionary War.)

Born in the trappings of wealth, Cadwallader David Colden III was shipped off to London for a proper education and returned to New York in 1785 to become a lawyer.

With his high class connections, he quickly acquired an impressive client roster, in particular Robert Fulton and Robert Livingston, assisting in their control of ferry services in New York harbor. He became New York district attorney twice, 1798 and 1810.

Advantageous Friendships

Colden was a different man from his ancestor; he even fought against the British as a colonel of volunteers in the War of 1812. Surprising given his lineage, Colden was for many years considered a Federalist, the party of Alexander Hamilton. However, he considered as one of his closest friends a rather unlikely ally — anti-Federalist DeWitt Clinton.

How they met probably had less to do with political alliances than membership of a rather notable society — the Freemasons.

In fact, Colden and Clinton were members of the city’s most influential — and still active — Holland Lodge. Within a few years, this affiliation would be political poison, with anti-Freemason candidates characterizing the secret organization as above the law and morally corrupt.

At Odds With Tammany Hall

Colden’s ascent into the mayor’s office caught him within some serious political crossfire. Cadwallader’s friend DeWitt became the governor of New York in 1817, making him the head of the Council of Appointments, which selected a mayor for New York, back in the heady days before elections.

Clinton would use his influence to install his friend in the job in 1818, but not without Colden sustaining a little political injury.

One evening, Colden was in Albany and was invited inside a tavern for a glass of wine. He suddenly realized he was in a room filled with members of Tammany Hall, political enemies of the Federalists.

Colden had once been a member of Tammany — during their less politically active days — and in 1793 had even spoke to an assemblage at Saint Paul’s Church.

He was now on the opposite side.

Immediately they pounced, urging him to not seek the mayor appointment. But no, he cried!

“He exclaimed energetically against the trickery, declaring that he had not asked for the office of Mayor, but would only accept it if offered.”

When Clinton did grant him the job, Tammany made sure to make life difficult for him. For the entirely of his three one-year terms, Colden became a pawn in the battle between Governor Clinton and the ascendant Democratic machine.

Colden began work in the spanking new City Hall, the fourth mayor for the new building after Jacob Radcliffe, John Ferguson and, of course, DeWitt Clinton.

Pigs and Prison Reform

First on Colden’s agenda: all those pigs running around.

He declared, “Our wives and daughters cannot walk through the streets of the city without encountering the most disgusting spectacles of these animals indulging the propensities of nature.”

Animals were penned up and steep fines charged to butchers who kept pigs unproperly supervised.

Colden also took a crack at the city’s deeper social problems. Indeed he was governing over a growing city, population 123,706 as of 1820. With a big city came big city problems — poverty, crime, homelessness.

The New York Society for the Prevention of Pauperism, led by the mayor himself, investigated prison conditions throughout the young nation to come up with a local solution.

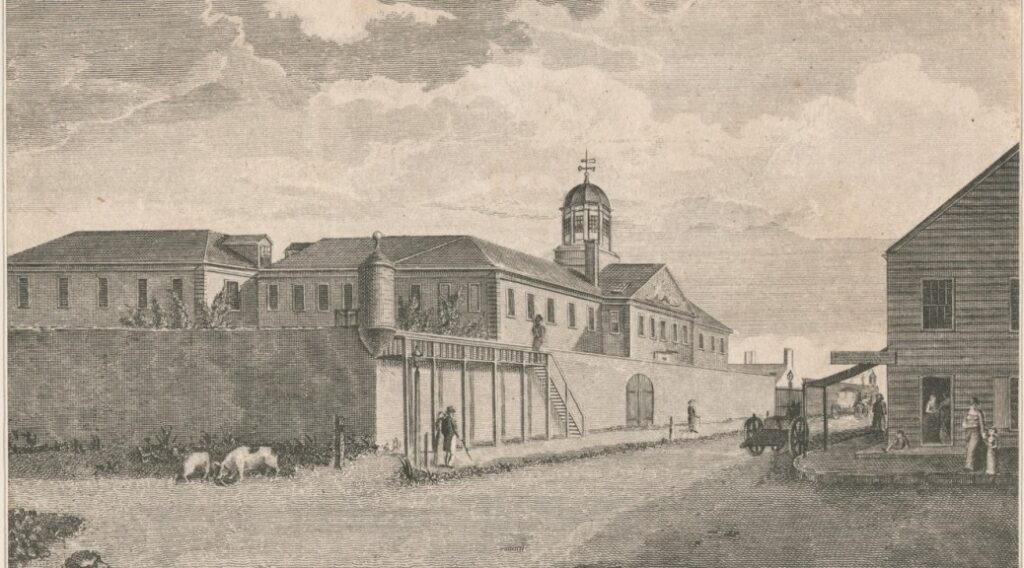

At the time, the state penitentiary lay in today’s West Village in a place called Newgate Prison. One of their findings was a need to separate younger delinquents from the adult criminals held there.

Colden proclaimed, “It must be obvious that under such circumstances it would be in vain to expect that their punishment will improve their morals: it can hardly fail to have a contrary effect.”

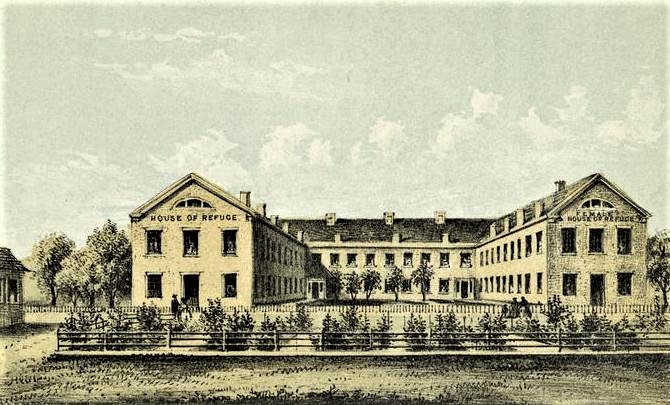

The mayor set the stage for an innovative experiment: New York’s House of Refuge, in an arsenal at Broadway and 23rd Street, essentially a reform school, built to incarcerate children age 16 and younger.

It later opened in 1825 (after Colden left office) with six boys and three girls as its pupils, many of them guilty only of homelessness and essentially kept here until adulthood. By the early 1830s, the House of Refuge would receive over 1,600 teenagers.

A ‘Kindly’ Anecdote

Like many mayors to follow, Colden also clamped down on liquor sales, even carrying around a ‘red book’ to notate violations and overheard complaints of local tavern owners.

Naturally, Colden would rally behind Clinton’s most ardent cause — the Erie Canal. It opened in 1825, after Colden left office, but his support did indeed pave the way for New York to become, in his own words, “one of the greatest commercial cities in the world.”

He was aristocratic, class-oriented but ultimately open hearted, they say. A reminiscence in the 1843 journal New Mirror quotes this certainly apocryphal story about the mayor’s ‘kindness’.

One rainy night on his way to a dinner party, Cadwallader stepped up to a ‘hackman’, a type of carriage taxi, for a ride.

The driver, “who had some old grudge against Mr. Colden,” rudely sped away, leaving the passenger on the curb. He jotted down the cab driver’s number and summoned him to City Hall.

“Poor Pat (for of course he was Irish)” as the article indicates, “went up the stairs, trembling at the fate which awaited him. When the mayor demanded to know why he was treated so rudely, the driver proclaimed,”you see I looked in your face, and, faith, you looked so like a jontleman I drove twice before that never paid me, I was afraid to thrust him agin!”

Colden laughed, exclaiming, “Your wit has saved you this time!” and excused the driver.

Colden’s Later Years

Aligning with Clinton eventually became a bad idea. When Clinton was turned out of the governor’s office, so too was Colden from the mayor’s office. But he still remained popular with New Yorkers, becoming a U.S. congressman, then a member of the New York state senate in 1825.

In later life, he engaged in a couple unusual endeavors. The first was the construction of the Morris Canal in northern New Jersey, a conveyor of coal that operated for over a century.

And in 1830, he briefly indulged in the hobby of horse racing, taking over the Union Course in Woodhaven, Queens. The closest you’ll get to visiting Colden’s racetrack is visiting Neir’s Tavern, the oldest tavern in the borough.

Colden died in 1834, in Jersey City.

For centuries his gravesite was unknown. But in 2011, historian (and friend of the show) Eric K. Washington discovered his grave at Trinity Church Cemetery.

Revision and expansion of an article which first ran on this website in 2009.

8 replies on “Mayor Cadwallader D. Colden: Leading the city over 200 years ago”

Yes, Grandpa would have been proud! Cadwallader Colden the Elder was a fascinating man. He was a Royalist who had spent over 56 years in service to the crown, but he also loved America.

A great way to gain insight into Colden the elder is to read his letterbooks — all 11 volumes of them. They are a wonderful collection of his letters written to and from family, friends like Benjamin Franklin, acquaintances, politicians, physicians, scientists, etc. You gain a picture of this remarkable man whose contributions to Colonial America have been minimized simply because he was on the losing side.

Today, even his burial place is lost to time … somewhere in Long Island on what was once his estate of Spring Hill. There is a memorial in the family cemetery in Newburgh but the actual grave in LI is lost forever.

Just wanted to point out something — Cadwallader David Colden is indeed his grandson, but is actually the son of David Colden and Alice Willett, and is not the son of Cadwallader Colden II.

The multiple Cadwallader Coldens in every generation makes it confusing but I am descended from Colden the Elder’s son, Alexander, and have gotten the family genealogy fairly straight.

David Colden was born on Nov. 3, 1733, and died in exile in England in 1784. He is buried in St. Anne’s Churchyard in Soho.

His son Cadwallader David Colden followed him into exile in 1784, and stayed in England to finish his education. While in England he was under the care of his aunt Elizabeth’s husband, Sir Anthony Farrington.

In the meantime his mother and sisters where under the care of his uncle Cadwallader Colden II in Newburgh.

Thank you for the neat write-up. You may already know this but if you are ever in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, you may want to look for the Colden portraits … There are two portraits of Cadwallader Colden the Elder and a couple of family members. They are in the American collection, I believe but a search of the Met’s website will bring up information.

Oops, sorry … forgot to mention too that Cadwallader Colden the Elder was not Irish. He was Scottish … he just happened to be born in Ireland while his mother, Janet Hughes, was visiting relatives.

His father, Alexander Colden, was a minister in the Church of Scotland in Berwick, Scotland.

Also, Colden’s book on the Six Indian Nations of New York was written in 1727 and updated in 1747.

I’m looking for a Colden descendent to compare DNA with, on a hunch, though the genetic distance may be too far for autosomal already. I am a 6x great-granddaughter of someone from Berwick, Scotland. The Colden name keeps coming up over and over again in family stories.

I just stumbled across your wonderful entry on Mayor Cadwallader D. Colden. It is worth adding a few additional points.

In 1815 he was president of the New York Manumission Society, in which capacity he oversaw the rebuilding of its African Free School that had burned down the year before.

In 1817 the NYS Legislature set July 4, 1827, as the date for the entire abolition of slavery in the state. For this act, Cadwallader D. Colden’s “energetic aid” was explicitly commended (along with the Society of Friends, Peter A. Jay, William Jay, Governor Daniel D. Tompkins and others) for having helped to bring about.

Apart from his statue on Chambers Street, Colden may now also be found 10 miles uptown. This summer I had the astonishment and privilege of rediscovering his forgotten gravesite in Trinity Church Cemetery (where Mayors Fernando Wood and A. Oakey Hall are buried, and where Edward I. Koch has already established his plot).

After several successive moves since his death in 1834–including three different locations within the cemetery between 1843 and 1869–he fell out of view. But he is there today in an obscure plot among the Astors. – Eric K. Washington

Here’s also a link to a photo I took of Cadwallader D. Colden’s grave: http://www.flickr.com/photos/90376097@N00/6292129412/in/photostream

Photo: ©2011 by Eric K. Washington

Great photos and article.

Which one of the 2 statues is CC?

Colden Avenue in the Pelham Parkway/Morris Park section of the Bronx was named for him.

Colden street in flushing (alongside the east side of Kissena corridor park) is also named for him. Maybe his estate was in that part of flushing?