The following article is an excerpt from a new Bowery Boys mini-podcast — following up on this week’s episode on the Hotel Pennsylvania — which has been made available to those who support the show (at the Five Points level and above) on Patreon.

In the latest episode of the Bowery Boys podcast on the history of the Hotel Pennsylvania, we discuss the musical landscape of Midtown Manhattan in the 1930s and how the unspoken social restrictions of the day played out during the rise of Big Band jazz.

In fact, the Hotel Pennsylvania played a very small role in the eventual elimination of color barriers in Midtown venues.

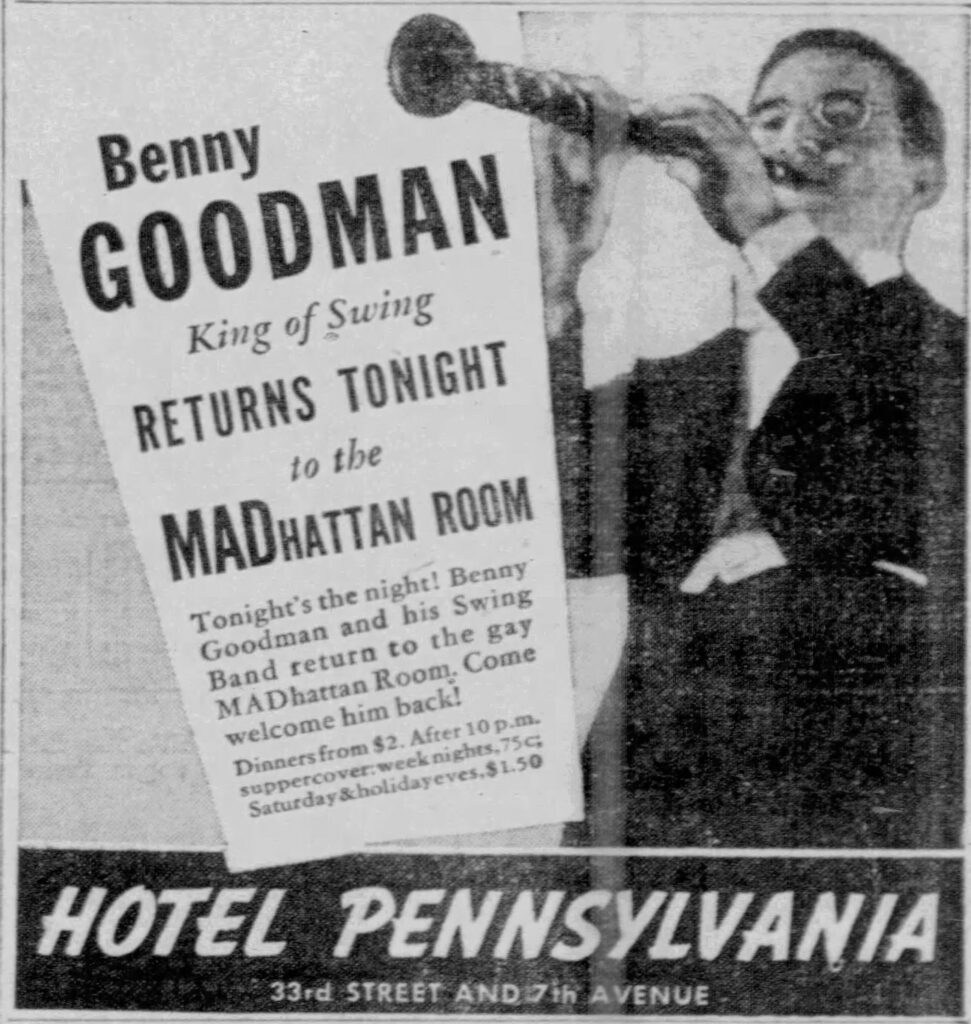

But this story has nothing to do with the Café Rouge, the legendary Big Band ballroom which hosted major artists and popular radio broadcasts. Rather the action takes place in the smaller club down on the hotel’s lower level — the Madhattan Room.

“It wasn’t as sumptuous or as glamorous as the Café Rouge,” one newspaper describes, “but it had fine acoustics and its small size and low ceiling lent an aura of immediacy conducive to jazz listening.”

It was here in the fall of 1936 that Benny Goodman, Gene Krupa and Teddy Wilson would make New York music history.

Breaking Barriers

While many white Big Band stars worked with black artists on arrangements and recordings — and they obviously sat in with each other during rehearsals — live public performances proved more difficult.

Black and white musicians were never allowed to play on stage with one another.

This was not merely a prejudice of the Jim Crow South. Venues in northern cities also held fast to this color barrier — particularly in hotel lounges and ballrooms.

That is, until Easter Sunday of 1936, during a tea dance at the Congress Hotel in Chicago, when between sets of Goodman’s regular orchestra, the bandleader debuted a new jazz trio — with Goodman on clarinet, Krupa on drums, and Wilson (an African-American musician from Texas) on piano.

It was the first time that a black musician played as a regular part of a white musical ensemble before a live paying audience. And it was only really accepted because Wilson did not actually play with the full band. Still, a moment is a moment.

According to the British jazz journalist Leonard Feather, “It was an historic precedent, the magnitude of which can hardly be appreciated today in correct perspective.”

The Trio Becomes A Quartet

Later that fall Benny Goodman came to the Hotel Pennsylvania and the Madhattan Room, his orchestra performing nightly.

The Madhattan Room would be Goodman’s on-and-off again home in New York, from September 30, 1936 to early 1938. And in between the band sets, Goodman would bring out Wilson and Krupa for a sweet trio interlude.

Soon that trio became a quartet in 1937 with the addition of another black musician — Lionel Hampton on the vibraphone.

While this decision might seem minor today — really, in service of the music as Wilson and Hampton were outstanding artists — some later compared Goodman to Branch Rickey, the president of the Brooklyn Dodgers who signed Jackie Robinson in 1945 and broke through baseball’s color barrier.

Hampton later said, “As far as I’m concerned, what he did in those days—and they were hard days, in 1937 — made it possible for Negroes to have their chance in baseball and other fields.”

You can hear one recording from one 1937 performance at the Madhattan Room here:

Highlights of Jazz History

But this subtle, somewhat nuanced and ironically quiet introduction to integrated live performances in New York gets immediately overshadowed by two major moments in music history.

In March of 1937, Goodman and his musicians played a two-week engagement at the Paramount Theater in Times Square.

Every night the auditorium was filled mostly with wildly enthusiastically hip teenagers, who scooped up the 25 cent tickets and sold out every night.

To quote from Goodman biographer Ross Firestone: “It was apparent to everyone — Benny and the band, the Paramount management, the assembled members of the press and the thousands of still ecstatic youngsters — that something truly momentous had just taken place.”

“By the time Goodman finished with “Sing, Sing, Sing” at the end of a forty-three minute set,” writes David Rickert, “it could be safely said that the Swing Era had begun.”

And at these shows, as they had done at the Hotel Pennsylvania, Goodman was joined on stage between sets by Wilson, Krupa and Hampton.

Then, on January 16, 1938, Goodman and record producer John Hammond brought together an epic collection of musicians to perform at Carnegie Hall.

This celebration of jazz artistry has been called the most important concert in jazz history.

For more information on New York City and jazz music history, check out these prior episodes of the Bowery Boys podcast:

1 reply on “Making Music History at the Hotel Pennsylvania”

Just reading in the NYT that the Hotel Pennsylvania is just about gone. Demolition is its cruel fate. NY has little respect for its own great history. Very sad.