One hundred and fifty years ago this month (more specifically, on January 7, 1872), a shocking assassination took place at the northwest corner of 23rd Street and Eighth Avenue.

And it took place at a quite surprising venue — the Grand Opera House. Surprising in the sense that it seems unusual that an opera house stood at this spot at all.

There’s a movie theater close by — and a theater for the School of Visual Arts just down the block — but I’d hardly call this intersection an entertainment mecca.

Above: the opera house in 1925 as seen looking east on 23rd Street. Below: in a picture from 1895

Pike’s Place

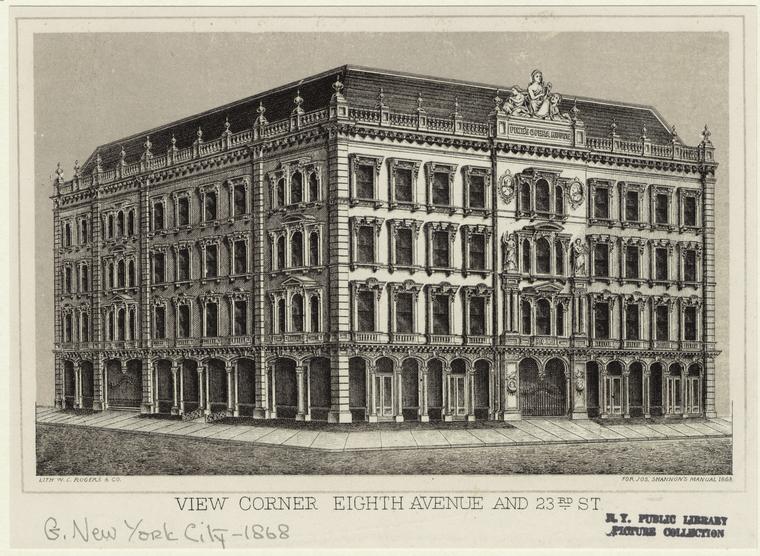

The opera house sprang up in 1868, the project of Samuel N. Pike, who purchased the land directly from Chelsea estate owner Clement Clarke Moore himself. In fact, the original Moore estate was located only a block away.

The Pike Opera House, as it was called in those days, was Pike’s play for legitimacy in New York. A German immigrant who arrived in the U.S. in 1837, Pike lived in New York for a few years and made his fortunes in wine imports. Aspiring to upper-crust tastes, Pike fell in love with opera music after viewing performances by PT Barnum chanteuse Jenny Lind.

The author E.T. Harvey painted an extraordinary picture of Pike in 1916:

“Samuel N. Pike was an extraordinary man in many ways. In appearance he was rather above the middle height, and slender. He wore a heavy, full mustache, after the manner of that period, and though dark complexioned, had very piercing steel-gray eyes. He had a short, abrupt way of speaking, and though good to his employees, was not familiar with any of them. He always dressed in the height of fashion, wore a silk hat and used perfume……

He was crippled in one of his fingers, but in spite of this was accounted a fine amateur flute player.”

Pike constructed a massive opera house in his adopted home of Cincinnati in 1859 and many years later built a companion here in Manhattan at 23rd Street. It officially opened on January 9, 1868.

He was banking on the growth of the New York theater along 23rd Street. Meanwhile the wealthy preferred the Academy of Music down on 14th Street. While some stages would come to 23rd Street, it would be the arrival of retail and Ladies Mile that would come to define this street by the 1880s.

A Stage for Scoundrels

The theater was spectacular — perhaps too spectacular for the location. “A striking feature seen on entering is the grand foyer, the largest in any theater in the city, open in part to the roof. A stairway of unusual width leads to the balcony….The stage, one of the largest in New York, is eighty feet wide and seventy feet deep, and the green-room is much the most extensive in the city.” [Kings Handbook]

The following year, Pike sold his lavish hall to two rather unlikely investors — Jim Fisk and Jay Gould, grade-A robber barons, pals of Boss Tweed and the orchestrators of the Black Friday Panic of 1869. Why would these two nefarious characters want an opera house?

Below: A detail from the Grand Opera House taken in the 1930s

The house’s upper floors doubled as the offices of their own Erie Railway venture. Fisk’s mistress Josie Mansfield was frequently installed into productions at the now-named Grand Opera House; it was even rumored her next-door apartment was connected to the opera house with an underground tunnel.

However it does seem that Fisk and Gould were legitimately aficionados of the theater, or at very least fans of the elite who would attend them, and the profits that would follow. The Grand Opera House would soon showcase a great number of theater endeavors outside of opera.

But unfortunately for Fisk (pictured below) the greatest show the Grand Opera House ever presented was his own wake.

The Murder of Jim Fisk

On January 7, 1872, Fisk was fatally shot at the Grand Central Hotel by Manfield’s new lover Edward Stiles Stokes. He died the following day. The robber baron was so associated with the Opera House that his body lay in state here, attended by thousands of mourners and perhaps tens of thousands of curiosity seekers.

“The showy coffin, liberally adorned with gold-plated ornaments, rested on two low stands, and in this, garbed in the gold-laced uniform of the colonel of the Ninth [regiment], lay Fisk, his mustache carefully waxed, white kid gloves on his hands, and his feet buried in white flowers, in various devices.” [source]

His business partner Gould would continue operating the Opera House for several years afterwards, eventually renting it out to vaudeville shows and ‘second-run’ Broadway productions, its fortunes disintegrating as theater moved uptown and the Chelsea neighborhood became more middle-class.

Changing the Scenery

Like many old stages before it, the Grand Opera House switched to films in the 1920s. RKO tried its best to rehabilitate the space, hiring Thomas Lamb to renovate the theater with modern flourishes, reopening the space as the RKO 23rd Street Theatre (seen below in 1927):

Outside the opera house-turned-movie theater:

The site remained a movie house through the 40s and 50s, finally closing on June 15, 1960. In a further indignity, the Opera House was thoroughly gutted in a fire.

Today a three-story office and retail building sits on the spot of the opera house. Most New Yorkers are familiar with this corner due to the Dallas BBQ which graces the corner. Fisk might have been way into their Texas-sized margaritas.

Portions of this story originally ran in an article on this site on August 18, 2009

4 replies on “Chelsea’s former opera house and the shocking murder of a New York ‘robber baron’”

Are you sure that photo above of the RKO 23rd Street Theatre was taken in 1927? Looks more like 1947.

… or maybe 1937.

That’s what I thought, so I looked it up. The photographer is Berenice Abbott and the photo was taken in 1937.

The 1937 double-header is “Married Before Breakfast,” with Robert Young and Florence Rice, and “Bank Alarm,” with Conrad Nagel.