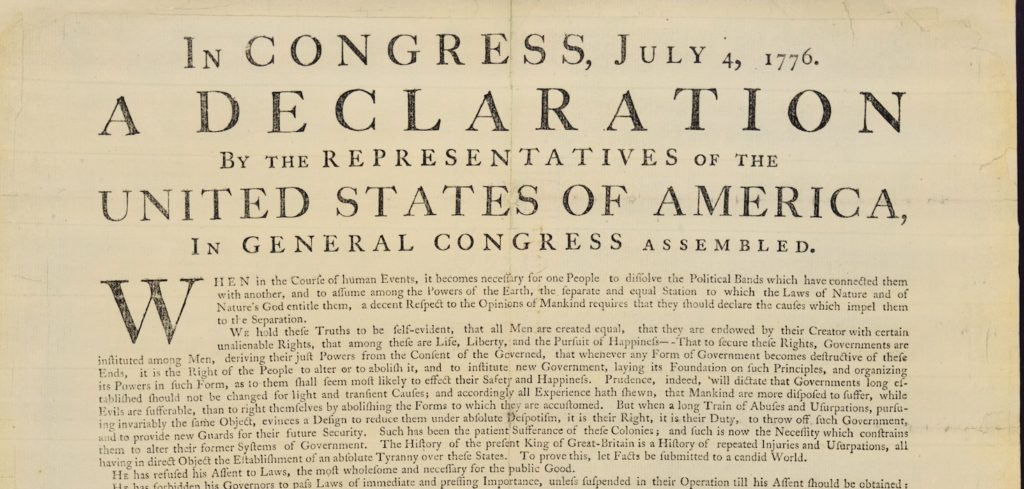

George Washington’s copy of the Declaration of Independence is perhaps the most well-known of the almost 200 copies first made of the document.

As a facsimile, it’s certainly not the the most valuable document held by the Library of Congress — after all, they have Thomas Jefferson’s actual rough draft of the Declaration, along with tens of thousands of his other papers — but it’s certainly an inspiring artifact in its own right.

Below: The document in question.

Because Washington wasn’t in Philadelphia at the time of the actual declaration on July 2 or the completion by Jefferson of the finished copy on July 4.

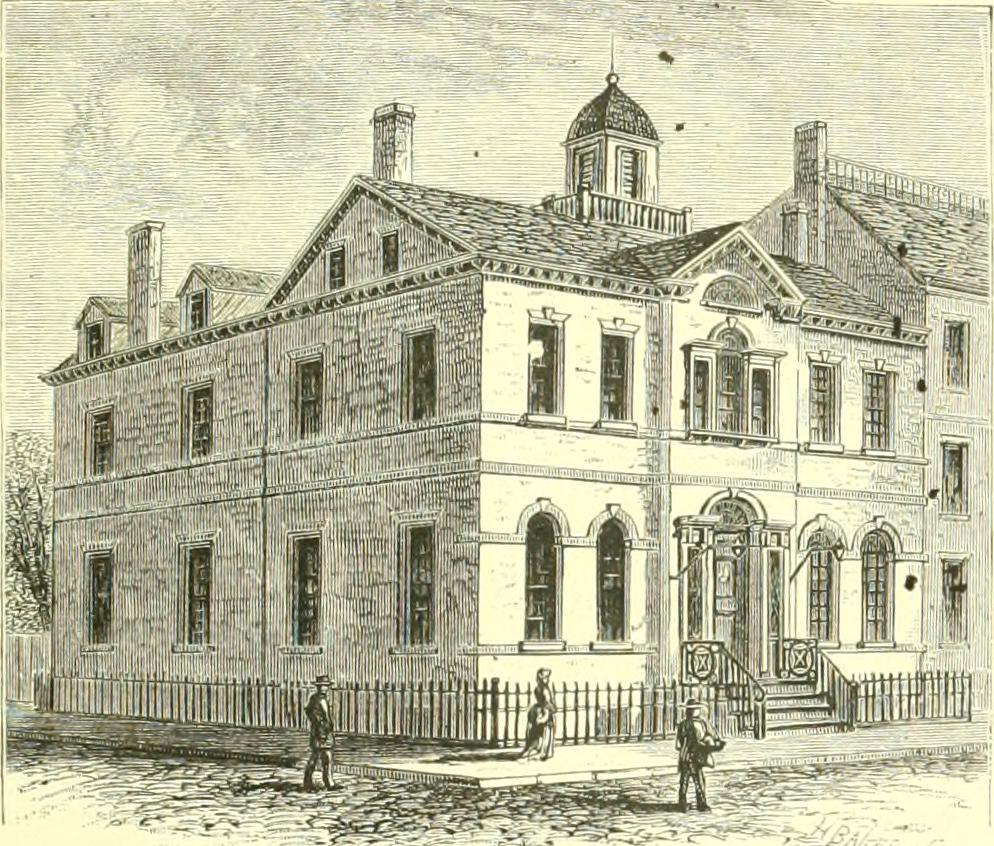

Indeed he had been stationed in Manhattan since April 9, 1776, headquartered at the Kennedy Mansion at 1 Broadway (pictured below), facing Bowling Green and the statue of King George at its center.

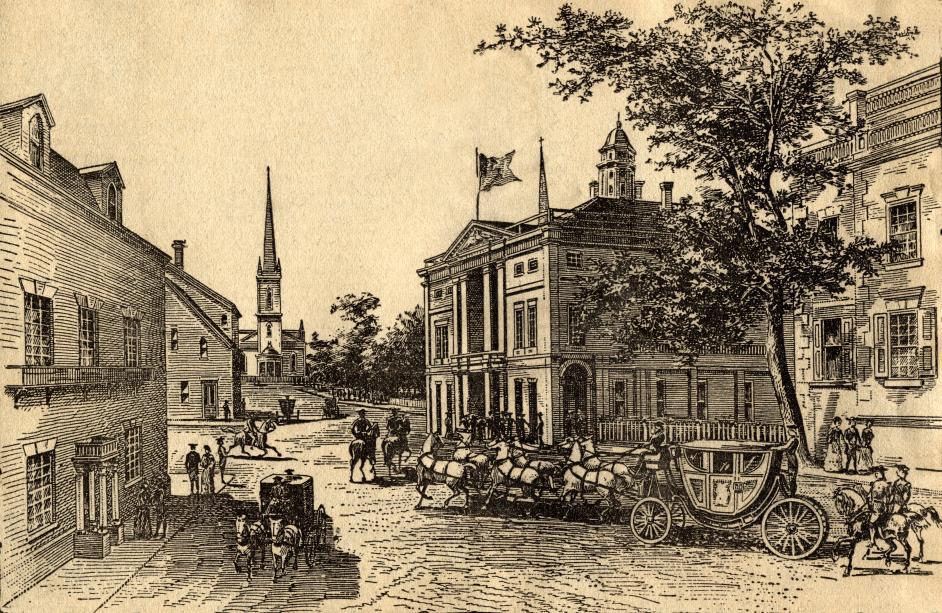

Later, as news of a British arrival to New York became evident, he moved his headquarters to City Hall, then on Wall Street and Broad Street.

Below: Washington’s two headquarters pre-July 1776:

Hundreds of British war vessels had stationed themselves off of Sandy Hook by the first of July, so fearful a presence that many of New York’s 20,000 residents had fled in fear.

By July 9, thousands of Continental Army soldiers had amassed in New York, turning the port town overnight into a military outpost. The key gathering point for Washington and his men was the Commons, a former livestock area that had been the scene of protests against the British for over a decade. Many a liberty pole had stood here, an age old protest against despotism.

But on that day, July 9, there was not a single inanimate symbol of protest, but rather many thousands of animate ones, all summoned to gather by 6 p.m. to await Washington’s words.

From the text of Washington’s order that day:

“The several brigades are to be drawn up this evening on their respective Parades, at Six O’Clock, when the declaration of Congress, shewing the grounds and reasons of this measure, is to be read with an audible voice.

The General hopes this important Event will serve as a fresh incentive to every officer, and soldier, to act with Fidelity and Courage, as knowing that now the peace and safety of his Country depends (under God) solely on the success of our arms: And that he is now in the service of a State, possessed of sufficient power to reward his merit, and advance him to the highest Honors of a free Country.“

A copy of the Declaration — the one pictured above — had been hand-delivered to Washington on that very day. However the General himself did not read it aloud. Rather he had one of his aides read it to the gathered crowd.

Imagine hearing these words for the first time:

“When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation….”

Below: A British map of New York as it was played out in 1776:

These weren’t empty phrases. Upon the completion of the reading, New Yorkers knew their city would be attacked. The men of Washington’s army knew they would fight and possibly die.

The words were greeted with joy, fear, anticipation and rage. The crowds surged with excitement. Most ran to their places — to Kings College, to the counting-houses of Hanover Square, to the ships docked along the East River — and prepared for the world to change.

Many people certainly ran to their local taverns to get wasted. (Samuel Fraunces must have hosted a lively crowd that night.) Some New Yorkers went to their homes, packed their belongings and fled.

Needless to say, the reading had gone off as intended. General Washington’s letter to the Continental Congress is an almost amusing example in understatement:

“Agreeable to the request of Congress I caused the Declaration to be proclaimed before all the Army under my immediate Command, and have the pleasure to inform them, that the measure seemed to have their most hearty assent; the Expressions and behaviour both of Officers and Men testifying their warmest approbation of it.”

In fact, not only did his army and the gathered New Yorkers approve of the Declaration, but later that night, they actively demonstrated their approval by rushing down Broadway to Bowling Green, where they proceed to pull down the loathsome statue of King George!

Afterwards, Washington had his personal copy sent to Artemes Ward, his major general stationed in Massachusetts. Washington’s note to Ward also survives:

“The inclosed Declaration will shew you, that Congress at Length, impelled by Necessity, have dissolved the Connection between the American Colonies , and Great Britain, and declared them free and independent States; and in Compliance with their Order, I am to request you will cause this Declaration to be immediately proclaimed at the Head of the Continental Regiments in the Massachusetts Bay.”

Today the Washington Declaration — or rather, a fragment of it — is only one of 26 Dunlap copies that are still believed to exist. It lives, naturally, in Washington D.C. However three copies of the ‘Dunlap’ Declaration are in New York City — at the Morgan Library, at the New York Public Library and another, in the hands of an unknown private collector.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, CHECK OUT OUR PODCAST ON NEW YORK CITY DURING THE REVOLUTION.

1 reply on “George Washington’s copy of the Declaration of Independence”

Awesome. Your post inspired me to recite the D of I into my voice recorder. Maybe my neice and nephew will enjoy it. You guys are helping to make learning fun!