On the 160th anniversary of the killing of Phillip Barton Key, I’m reposting this article from 2014 which originally ran on the 100th anniversary of Daniel Sickle’s death.

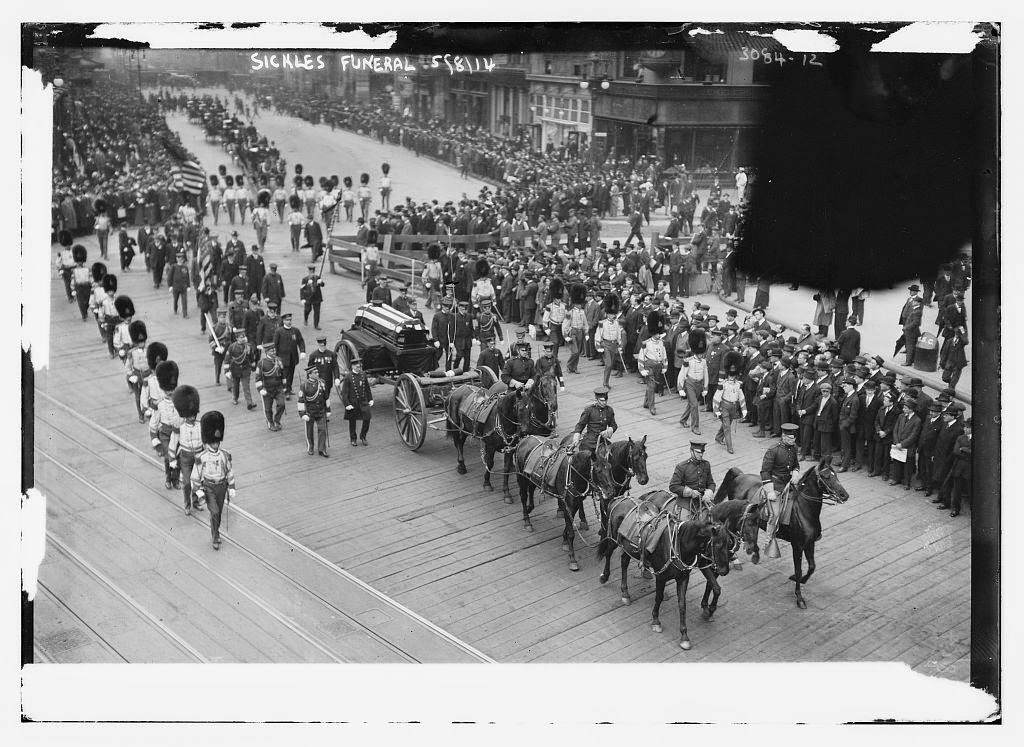

We don’t have large, parade-like funeral processions marching up the avenues as they once did during the Gilded Age and in the early years of the 20th century.

These events were times of public mourning and a bit of festivity. Most often they involved the passing of a well-connected political leader or a popular entertainers. They were somber and reverent affairs; afterwards the saloons along the side streets benefited graciously, tributes and toasts into all hours of the night.

1914

On May 8, 1914, New Yorkers filled the streets — from Fifth Avenue up to St. Patrick’s Cathedral — to mourn the passing of Daniel E. Sickles, one of the city’s most heralded war veterans.

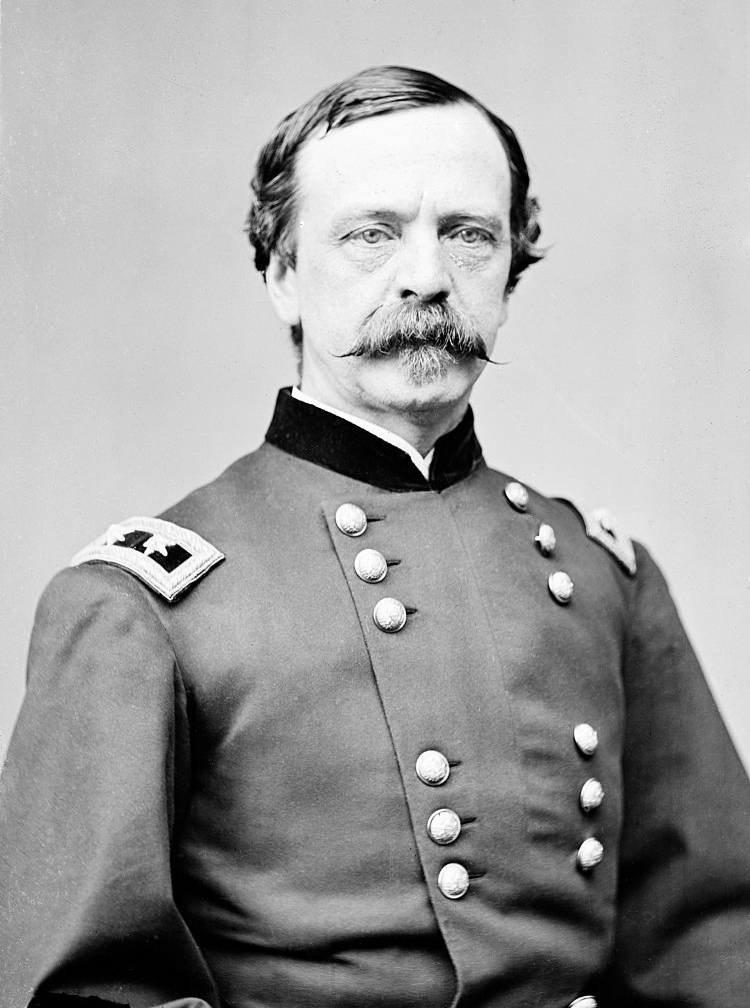

Having marshaled up volunteers in New York in the early days of the Civil War, Sickles distinguished himself as a bold and commanding general, gathering military promotions through sheer ambition. (He was one of the few commanders in Abraham Lincoln’s army without a West Point education.)

During the Battle of Gettysburg, Sickles was severely injured and had his right leg amputated. (Below: Sickles in 1862.)

He spent his years after the war polishing his war credentials and maneuvering from one political appointment to another. Sickles belatedly received the Medal of Honor and, situated from his home at 23 Fifth Avenue, was acclaimed in later life in one of New York’s greatest living veterans.

Sickles’ military career, however, was built as an exercise in reputation rehabilitation. When the war with the South arrived, he saw an opportunity to change the conversation about himself. His bravery in service to the Union, never questioned, served a dual purpose for Sickles. Today we might call this “re-branding.”

For in the years preceding the Civil War, the young politician was also known as a cold-blooded murderer who held a unique distinction in the history of legal proceedings.

1859

In April of 1859, New York Congressman Daniel Sickles became the first person in history to ever be acquitted of a crime due to temporary insanity.

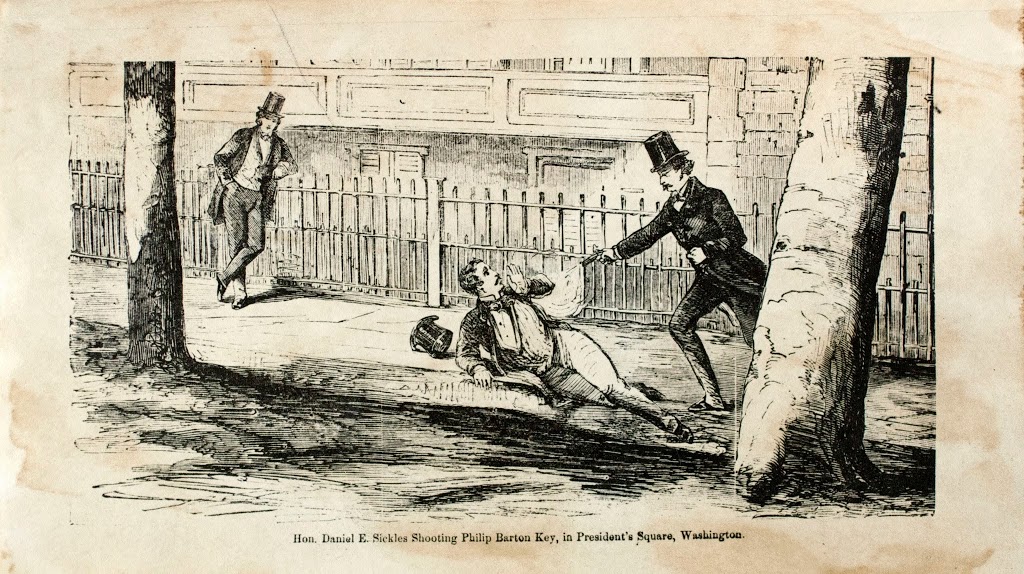

The crime in this case was the February murder of Philip Barton Key II, the son of Francis Scott Key, author of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” the national anthem of the United States.

Their lives almost resemble an episode of House of Cards. Key had been having a very open affair with Sickles’ wife Teresa. (Pictured below)

Daniel, however, was something of an epic rake himself. With no thought to his own or his wife’s reputation, Sickles was once passionately obsessed with the New York prostitute Fanny White, going so far as to take her into the Albany assembly chamber for a tour. There were even rumors that some of Sickles’ campaign election costs were covered by White.

But Key was hardly a wallflower; the famous son was a charming widower who bewitched the women of Washington DC with his intelligence, elegance and wealth. He and Teresa met in 1857 and began their affair soon after, meeting often once a day and openly flirting with each other at a society balls. (Below: An illustration of Key which ran in Harper’s Weekly in 1859.)

When Sickles did finally discover the affair, he was distraught and sickened, before turning violently angry.

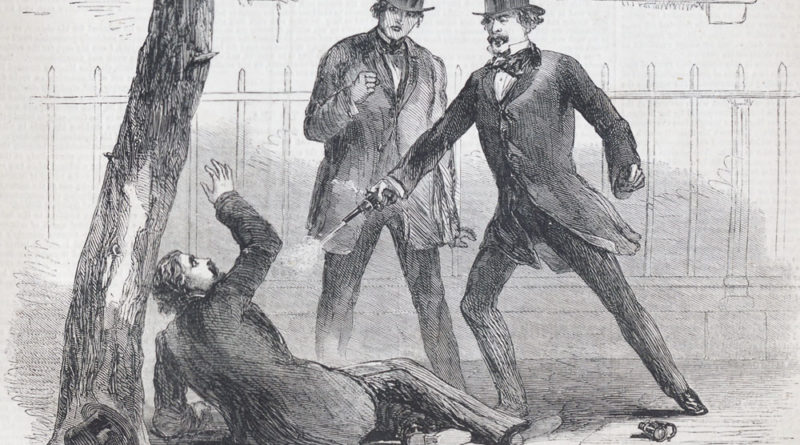

On February 27, 1859, Sickles approached Key in DC’s Lafayette Square — a short distance from the White House –and shot him in the groin.

“You villain, you have dishonored my house, and you must die!” Sickles reportedly said.

He shot Key again in the chest and would have shot him directly in the head had the gun not misfired.

Said the New York Times the following day, “The vulgar monotony of partisan passions and political squabbles has been terribly broken in upon to-day by an outburst of personal revenge, which has filled the city with horror and consternation.”

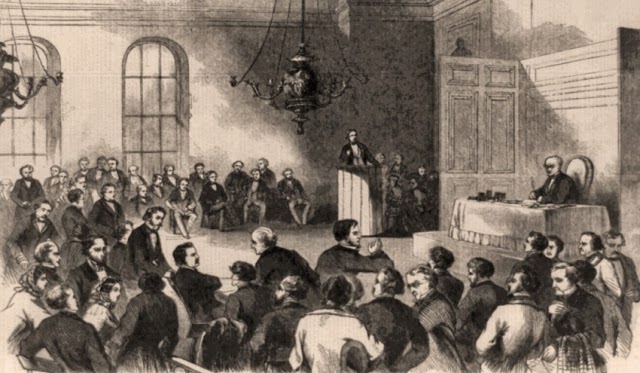

Above: An illustration of the Sickles trial, courtesy Library of Congress

The condition of Sickles’ mental state during and following the murder would be closely dissected in court. A colorful swath of testimony described Sickle as everything from disturbingly serene to a raging lunatic.

According to authors Michael Lief and H. Mitchell Caldwell, “These conflicting stories may be exaggerations on the part of creative witnesses, or they may be evidence that Sickles was driven to the edge, past the breaking point, entirely out of his mind.”

One of the lawyers who helped craft the insanity defense was Edward M. Stanton, later to be Abraham Lincoln’s Secretary of War. Their defense of temporary insanity — never successfully tried in a U.S. court — was sprung upon the jury, nested within an extravagant bed of prose, classical quotations and moral quandary.

“It is folly to punish a man for what he cannot help doing?” asked associate defense attorney John Graham. Apparently so, it seems, for in April, a jury acquitted Sickles, taken with the plight of a man wronged by his unfaithful and deceitful wife. (His attorneys did a spectacular job of burying Sickle’s own unfaithfulness and deceit.)

Above: 23 Fifth Avenue, the home of Daniel Sickles and the location of his death on May 5th, 1914 (images courtesy New York Public Library)

1914

Fifty-five years later, Sickles’ many legitimate accomplishments (and, let’s be honest, his relentless self-promotion) assured that this unusual crime was rendered a footnote when he died on May 5.

His New York Times obituary is an extraordinary bit of word play: “Philip Barton Key … paid attention to Mrs. Sickles, and Sickles shot and killed Key on the street in Washington D.C. on February 27, 1859.”

The focus then turns on Sickles’ “gracious” forgiveness of his wife: “I am not aware of any statute or code of morals,” said Sickles to his critics, “which makes it infamous to forgive a woman….I shall strive to prove to all that an erring wife and mother may be forgiven and redeemed.”

In reality, the two never reconciled. Teresa died in 1867 at age 31, her reputation destroyed. A few years later, Sickles became the ambassador to Spain, returned to his legendary womanizing and eventually married a well-connected daughter of a Spanish official.

He spent his final years at his Fifth Avenue home nearly bankrupt, his only means of support coming from his children and his now-estranged second wife. “[S]everal attempts were made to seize the art treasures in his Fifth Avenue home because of debt,” noted the Times.

Below: Daniel Sickles at a 1913 Gettysburg reunion, accompanied by his live-in secretary Eleanora Wilmerdirg